Earlier this year, the Trump administration announced plans to roll back federal emissions standards on consumer vehicles made in 2022 and beyond, which would have become more stringent under Obama-era direction. Gov. John Hickenlooper then signed an executive order in June directing the state to figure out how to stay the course.

On Friday, the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission, a division of the state's health agency, approved a measure to put Colorado emissions standards on par with California's, which have long been more restrictive than the rest of the country's. That means automakers must sell cars in the state that comply with these lower standards. Critics of stricter regulations say the costs of cars will rise. Supporters say the costs of weaker regulations show up elsewhere -- like in public health.

Colorado is the 13th state in the nation to align itself with California (plus Washington, D.C.). The measure passed unanimously, besides one commissioner who abstained from the vote.

As the biggest concentration of people in the state, the metro area is one of the largest drivers of greenhouse gases from vehicles in the region. And the number of cars on the road here is growing.

There are more and more cars on the Front Range. (We know you've noticed.)

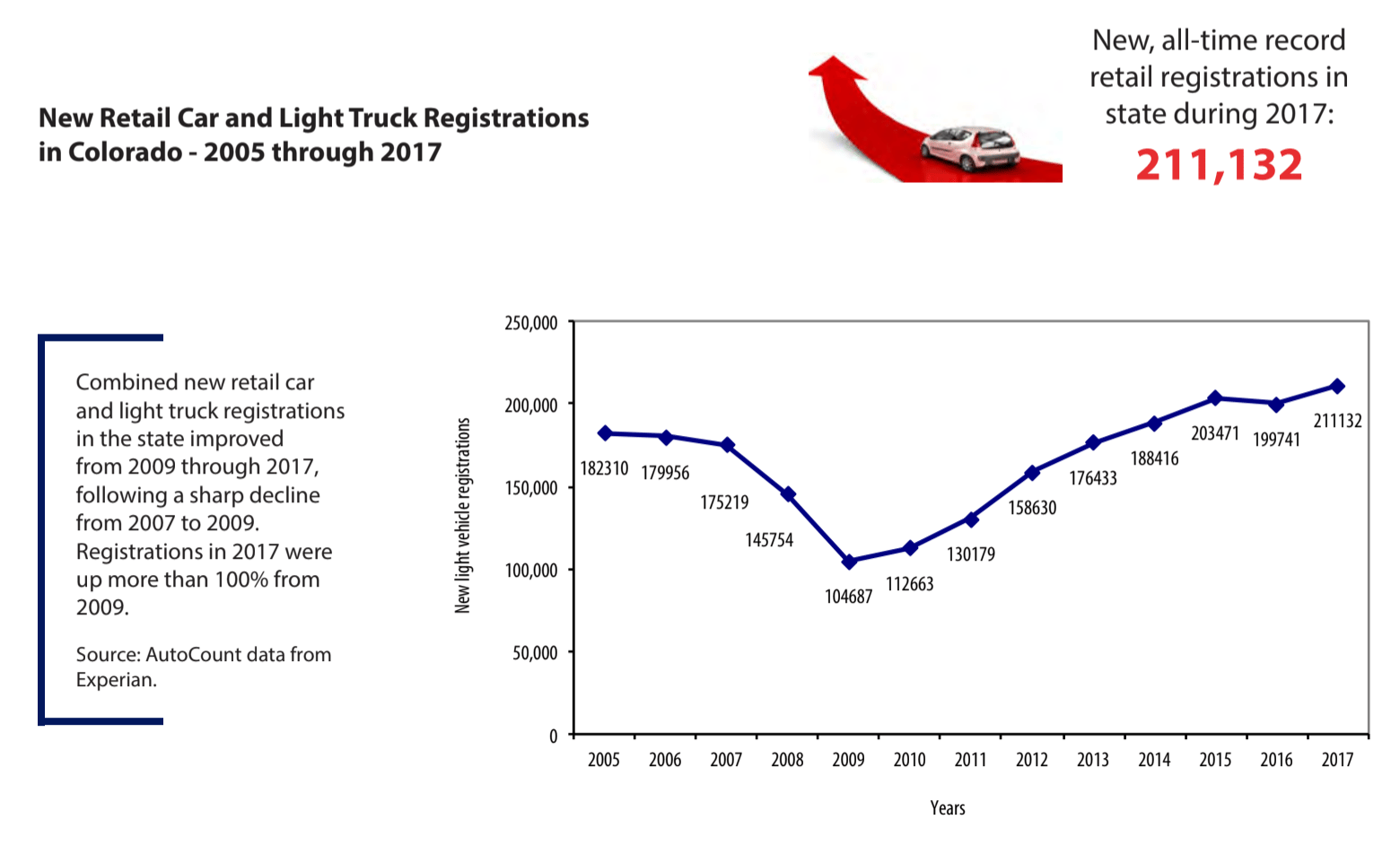

A 2018 economic impact report by the Colorado Automobile Dealers Association shows that new car and light truck purchases have been steadily growing since the Great Recession in 2018. While new car purchases dipped slightly this year, 2017 represented an "all-time" record high for dealers.

State numbers show that, in 2017, about half of all "passenger" vehicles registered in the state, both new and used, came from Adams, Arapahoe, Denver, Douglas and Jefferson Counties. Denver County, by itself, represented about 12 percent of the overall total.

And our drivers' presence has also been measured outside of the economic realm. The Front Range has struggled with ozone pollution - we're out of compliance with EPA standards - and a report last year from the National Center for Atmospheric Research estimated cars around Denver contribute as much to that problem as oil and gas development.

"For sure, Denver is a significant contributor to carbon pollution because of size and density," Jacob Smith, executive director with Colorado Communities for Climate Action, told Denverite.

His coalition represents communities from all over the state who are pushing measures like the one that passed last week. Westminster, Boulder, Golden and Fort Collins are among the 20 cities and counties that have signed on. Denver is not currently a member of the coalition.

While Denver has rolled out a number of reports and initiatives to address the city's environmental impact, Smith said action to deal with tailpipes really needs to come from the state level.

"The city of Denver can't set its own fuel economy standards," he said. "It needs effective state policy."

Many of the municipalities that have signed onto the Climate Action coalition represent mountain areas, like Vail, whose snow-fueled winter sports revenue is at stake as global average temperatures rise. But Denver, Smith said, has a lot on the line, too.

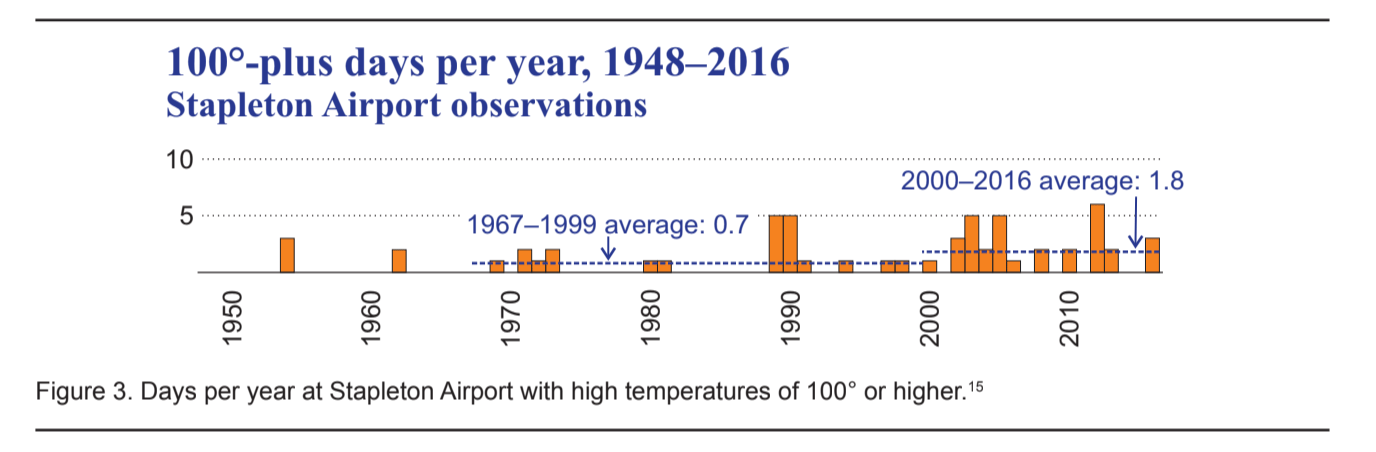

A study by the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization found that peak temperatures at the old Stapleton airport were more than 250 times more likely to breach 100 degrees since 2000 than between 1997 and 1999.

That, Smith said, "is a real impact on air conditioning costs for low income and elderly residents" in the city. Beyond that, he added, more frequent and intense droughts will likely threaten water supplies, both in terms of snow runoff could decrease (we saw how bad that can get last summer) and in how wildfire debris can taint mountain reservoirs.

Climate change can be a bleak topic, but Smith and his colleagues are happy to see Colorado positioning itself to be a part of a larger solution now that we've upheld the Obama-era emissions regulation.

"This is a smart and forward-looking decision," he said.