Janet Feder imagined a cozy, quiet life when she moved into her home in Denver's Cole neighborhood. When it was purchased in 2006, the house was a wreck: not quite condemned, but in need of serious renovations that Feder mostly did herself as it transformed from dilapidation to cozy cottage.

She rented it out for a while and then moved in. Life was good, but then construction on Denver's 39th Avenue Greenway project broke ground next door and her quiet life at the neighborhood's edge was suddenly broken by the sound of trucks. Construction noise and vibrations have continued to bother her, but it was the dirt they started excavating that became the source of real concern.

Much of north Denver, from the city's upper reaches down to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and from the river to Colorado Boulevard, is encompassed by the Vasquez/I-70 Superfund site. Superfund is a federal designation used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for environmental cleanup, often when there's nobody around who can held accountable. In this case, the pollution in question was mostly lead and arsenic, and historic.

In the next couple of weeks, EPA representatives say the agency will likely file the first motion to close out that site's largest section, called Operable Unit 1 or "OU1." But the unit is limited specifically to the top six inches of soil in residential yards. That's where Feder's unease comes into play. Her yard was part of a cleanup that took place in the 2000s, but the construction site beyond her fence is not. So she began to wonder: could these piles of dirt be toxic?

That fear has become a hot-button issue for some local activists who have been vocally raising similar concerns to the EPA and state and city health agencies. And it's not limited to Cole: a number of major projects are unearthing soil across northern neighborhoods from Globeville Landing Park to the expanding I-70 corridor.

Representatives from all three government agencies have responded by saying any contamination they might dig up will be dealt with properly, that people don't have anything to worry about. But for residents like Feder, who say their houses are often sprinkled with particles from nearby construction, there's still unease about what might be lingering in the ground.

This soil pollution dates to the turn of the century, but it wasn't discovered until the 1990s.

Back in 1993, the state of Colorado settled with Asarco Globe, a smelting company in north Denver whose stacks had sprinkled lead, arsenic, cadmium and zinc -- toxic stuff -- into Denver's northern reaches. The state originally filed for Superfund designation, but Asarco agreed to clean up the contamination themselves under a "consent decree" and Superfund was never declared.

But the decree required the state to investigate more yards radiating out from the site until they found clean soil. Their investigation revealed that smelter pollution was more extensive than they'd thought.

"We found a clean block to the north," Fonda Apostolopoulos, a project manager with the Colorado Department of Health and Environment (CDPHE), told Denverite, "but to the south, we kept finding more and more numbers and they kept going up."

Apostolopoulos and his team know how pollution moves on an intimate, physical level. Airfall from Asarco shouldn't have come this far south. A particle of lead, for instance, should have dropped to the ground before getting this far.

"It made us raise our eyebrows," he said. So they started looking for a new culprit.

The state appealed to the EPA for help and, Apostolopoulos continued, "They identified the Omaha Grant smelter as the possible source."

Their work led to the creation of the Vasquez site, and cleanup was confirmed to move forward in 2003. Like Asarco, this new cleanup revolved around lead and arsenic that was thought to have sprinkled onto North Denver. But while Asarco was operational into the 2000s, the Omaha Grant smelter hadn't been active since 1903.

Denver, like many cities across the nation, has to face pollution that dates back to an era when regulation didn't exist.

Andrew Ross, an environmental program manager for the city health department who works closely with the North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative, said most of the pollution they deal with in city soil is historic.

"When buildings were demolished before roughly 1965, 1970-ish, they just imploded it into the basement and then covered it up, so that's what we find," he said. "Construction debris, foundation debris in the soil all mixed together, and usually that's what we need to pull out."

Buried oil tanks near rail lines and old gas stations are common sources of ground pollution across the city. It was legal for residents to burn garbage in their backyards until 1951, so Ross said they're always finding contaminants in soils related to that. His job often takes on a kind of detective role, investigating old maps and phonebooks to figure out what was on properties, then they go out and take samples.

But the city and state have been more proactive in testing ahead of the huge projects reshaping north Denver.

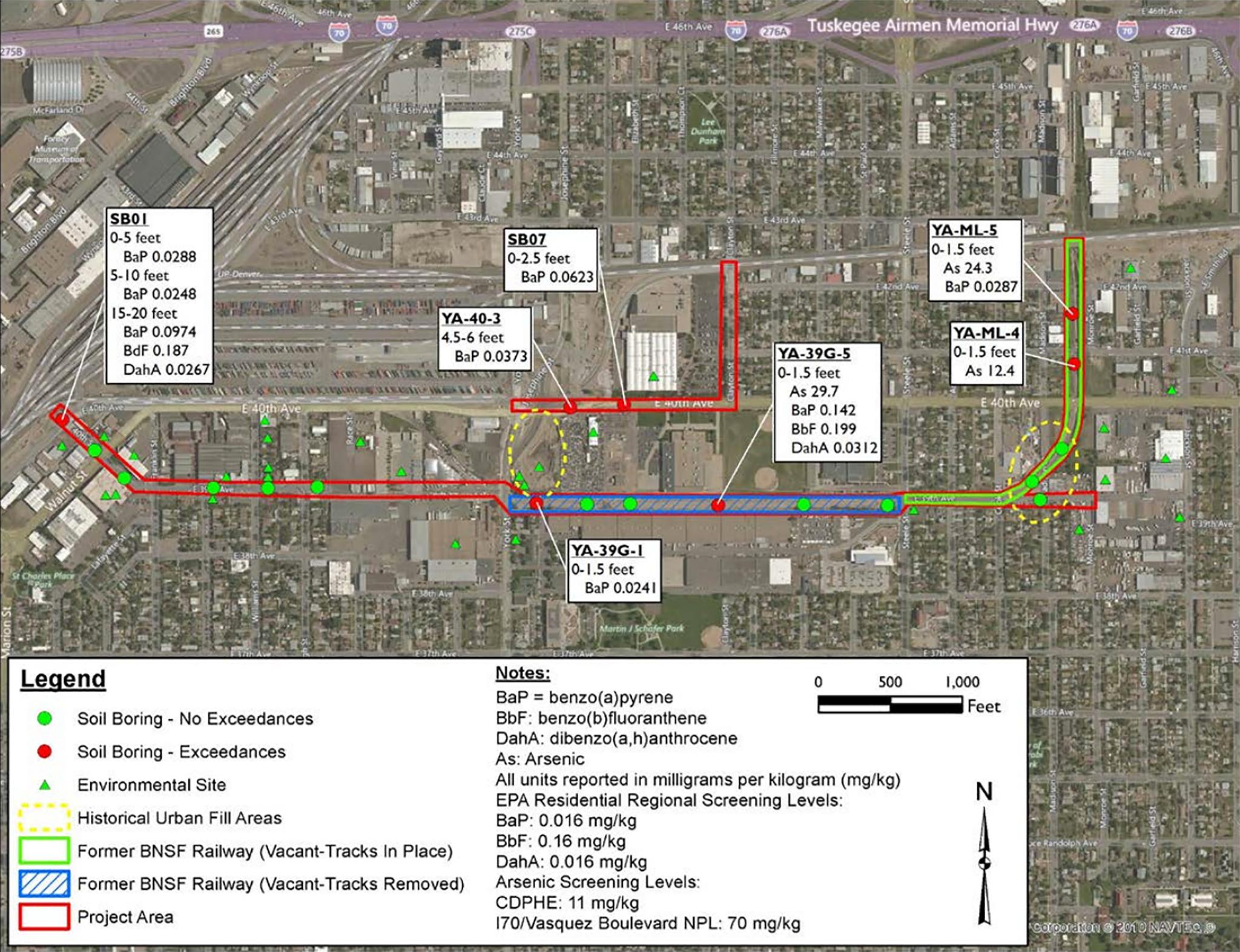

For the 39th Avenue Greenway project, which passes through that lot next to Janet Feder's house, the Denver Department of Health and Environment (DDPHE) hired a private testing company to report on what they might encounter. Of 19 soil cores sampled throughout the project area, seven contained pollution that exceeded state or regional standards.

One of those came from the lot next to Feder's home. The material there was described in one report as "trash and organic material" with "no odor." It contained arsenic that exceeded state guidance and benzo(a)pyrene, which is associated with combustion (like burned trash), that exceeded regional guidelines.

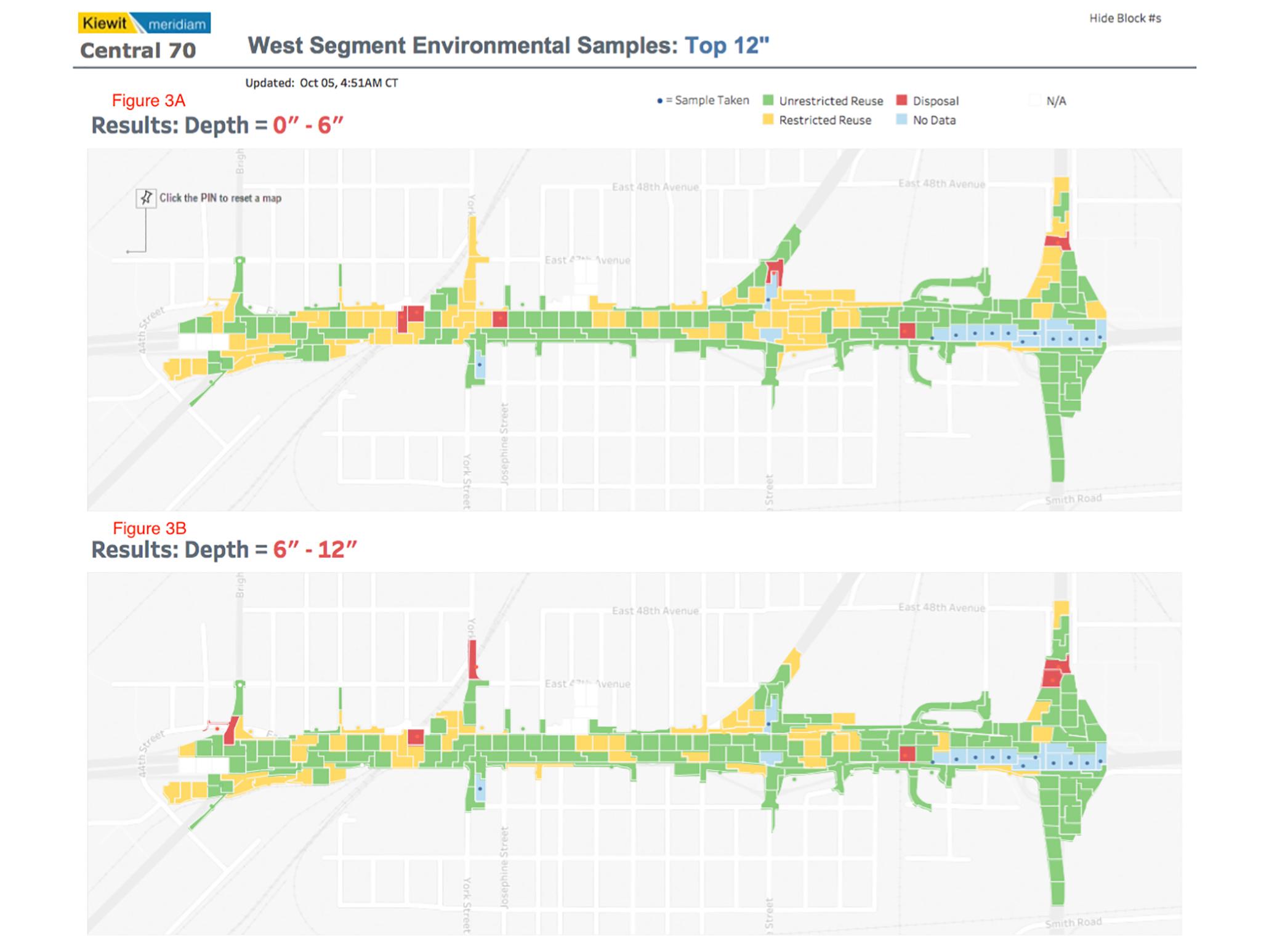

The Colorado Department of Transportation and contractor Kiewit Meridiam Partners also oversaw extensive soil testing along the I-70 corridor as they prepare to lower the highway below grade. Their report on about 2,100 samples was released in November.

At a community meeting last month, Megan Wood, an environmental manager for Kiewit, said the sampling was a measure to show residents they recognized their concerns.

"We know this is a hot topic for the communities," she said, so they asked themselves: "How do we get in front of this?"

Like the 39th Avenue testing, the I-70 report found pockets of contamination that exceeds residential standards, though they represented less than 20 percent of samples. The pollution they found was mostly arsenic and benzo(a)pyrene, as well as a handful of other compounds that are also related to combustion and industry. It's worth noting that, besides smelter smokestacks, arsenic is also found naturally in Colorado's soil at higher levels than the rest of the country.

Gordon Pierce, program manager for the state's air quality analysis team, told Denverite that the compounds found in the report probably come from "a mix" of sources that relate to industry, diesel emissions and leaded gasoline.

So, there is pollution in the soil, but is it dangerous?

The fact is, cities like Denver contain more pollution than is practical to clean. For agencies like DDPHE, CDPHE and the EPA, questions of safety are about exposure.

Kara Edewaard, an environmental policy analyst with the city said it comes down to: "What is the risk to public health and environment today? If you're looking at a 20-foot depth," for instance, "there's not a risk to human health."

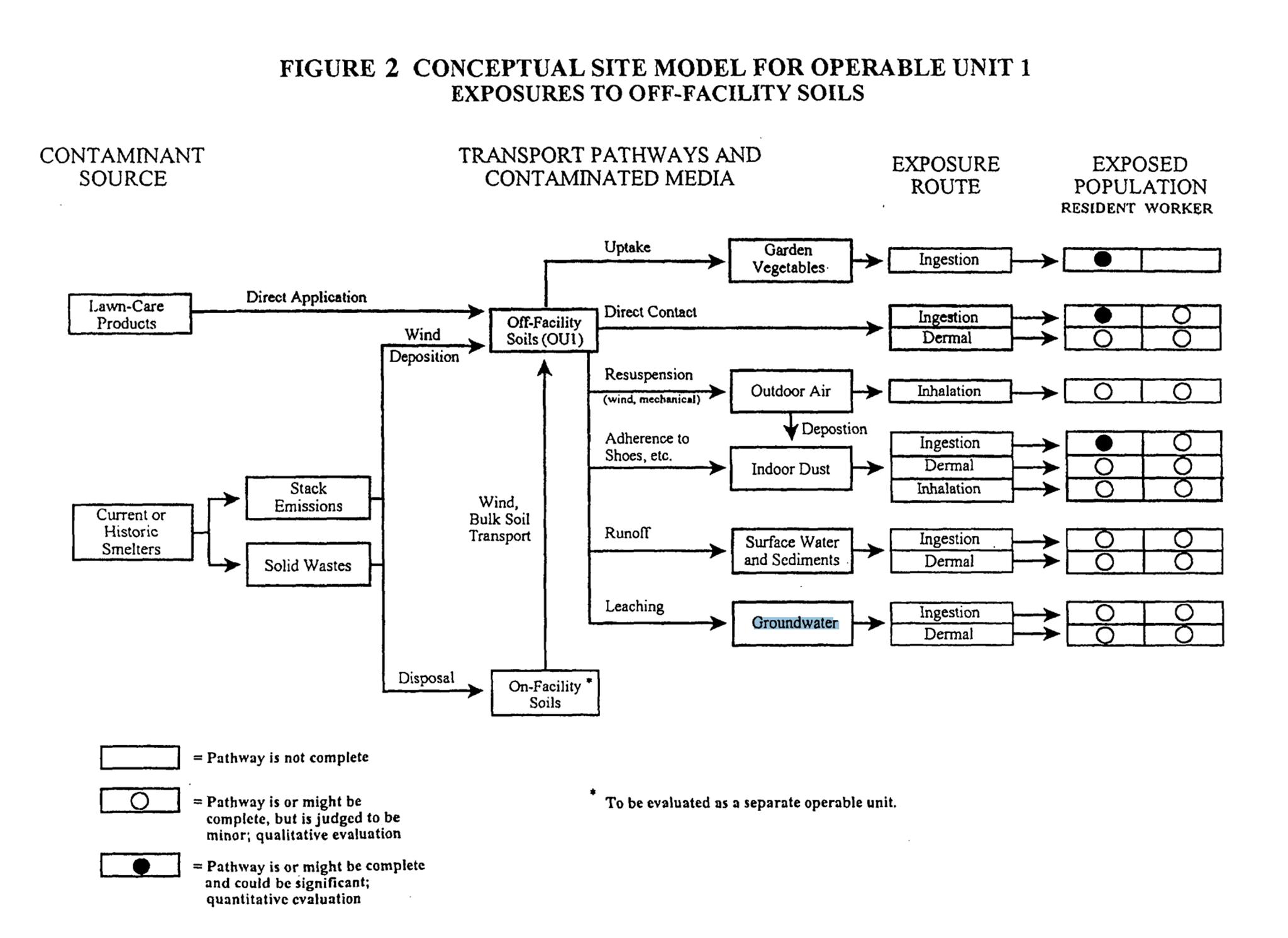

The reason OU1 was limited to residential yards comes from this concept, what's called a "pathway to exposure." The fear was that children might eat contaminated dirt and get sick. Replacing that soil was thought to remove most of the risk.

"Standing next to lead-contaminated dirt, there's no exposure," Ross said. "It has to enter your body somehow."

But this doesn't address fears that someone like Feder living next to an industrial area might have about proximity to sites that weren't cleaned. And because Superfund is an extremely narrow designation, it doesn't address other legacy pollution that's not from smelter chimneys.

To deal with pollution while they're digging, big projects use "materials management plans" that lay out how contaminated dirt should be dealt with.

The materials plan for the 39th Avenue Greenway project, for instance, requires that dust monitors be present on all worksites and daily field notes be filed to keep an eye on what crews encounter. It stipulates that any excavated soil must be disposed of properly -- they can't just dump it in the river -- and any pollution they do come across must be taken to special landfills meant to hold toxic materials.

The city maintains air quality sensors on some of these sites, including the one next to Feder's home. In her backyard, there's a table that's been coated with dust since construction started, one reason she's concerned. The city's monitors have generally not detected particulate levels that exceed standards, though particulates did spike in April the week Denver saw intense winds.

Whether or not contaminated soils could affect groundwater is another question.

In analyses done for the OU1 and 39th Avenue project, groundwater impacts were generally not examined. The materials management plan for 38th Avenue says their work will take place at least 10 feet above the nearest aquifer, so monitoring it is not necessary. The I-70 Superfund Record of Decision states that a contamination pathway to groundwater "is or might be complete, but is judged to be minor." While two other operable units in that site, which are much smaller than OU1, do take groundwater into account, the Superfund site at large is listed as having "insufficient data" to determine if water contaminated by stuff in the soil could make its way to the river.

Whether it matters again comes back to a question of exposure. Denver has very few wells and all residents' faucets are fed from Denver Water's supply, which mainly comes from snowmelt. Like soil, if shallow aquifers are polluted but nobody's drinking it, there's not really an impetus to do anything about it.

John McCray, a professor at the Colorado School of Mines who specializes in the relationship between soil and water pollution, told Denverite that it is possible Denver's contaminated groundwater could become someone else's problem downstream.

"For the South Platte in general, I think, all groundwater is connected," he said. "It could show up in somebody's well in the future."

While he said it's unlikely that anyone in Denver would be affected by bad water, he says he understands why someone who lives near a polluted site would raise questions. He would, too.

"If I lived there, you'd better believe I'd be digging in," he said. "I would be concerned and would want to know."

There are also questions about how pollution will affect future water needs. As we struggle with worsening shortages in the dry west, McCray imagined a day might come when we start looking at using shallow groundwater, and it will matter then if it's polluted.

Denver is not currently looking into accessing its shallow aquifers, but municipalities are exploring this in California.

Newsha Ajami, a director of Urban Water Policy at Stanford University, told Denverite her state is talking more and more about these water sources as droughts get worse. Historic pollution will make accessing them more expensive.

"Of course we should care but you have to understand," Apostolopoulos said, "it's part of living in the big city."

What he's getting at is a tension between the pollution we've accrued since Denver's founding and the impossibility of cleaning it all up. Now that the city and state have regulations, new pollution ought to be dealt with ahead of time. But we all will continue to deal with bad decisions from the past.

"It's a never-ending battle that's going to go on forever," he said. "We can't solve everything but we do the best we can."

Kim Morse, administrator of a community advisory group for the Vasquez Superfund site that now operates independently, summed up residents' concerns at a recent EPA meeting about the project.

"What we're looking for is some security. Something that would make us feel comfortable," she told the room.

Apostolopoulos told Denverite there's little he or anyone from another agency can say to deliver that comfort.

"I give them the information and they don't believe me," he said. "People treat you as if you're a liar."

Even still, he gets it. It's an emotional matter, especially with kids involved: "If I had kids, I'd be concerned also."