Note: This story was published on Jan. 3, 2019.

Maybe it's the War on Christmas.

Or maybe it's just Denverites wondering why the City and County Building, their seat of government, is bedazzled in religious symbols like angels, five-pointed stars and a biblical diorama -- two, actually -- depicting the Christian messiah's birth.

Whatever the reason, the question comes up every holiday season: Aren't religion and government supposed to go together like peanut butter and pickles? Why does Denver have a creche, or nativity scene, on the stairs of the building in which lawmakers vote and judges rule?

"It's not an explicit endorsement of a religion," said Mike Strott, a spokesman for the Hancock administration.

Local and national courts have concluded that baby Jesus, the Virgin Mary and other biblical characters are fine to display on government property as long as they're surrounded by traditional (but not necessarily religious) symbols. Think snowflakes and Santa Claus. Taken together, the creche does not promote Christianity, according to the courts.

That's why the nativity scene is allowed. But lots of things are allowed that don't necessitate doing. Also like peanut butter and pickles.

"I think we only need to care about it if it's exclusionary. I mean, Christmas was plopped on top of a pagan holiday," said Rebecca Hale, the Colorado Springs-based president of the American Humanist Association. "You just can't own December. It belongs to everyone."

Kwanza kinaras and Hanukah menorahs are allowed, but you won't find those on city property this year. (A donated menorah has been used in the past.) So Denver's policy is technically inclusive, but not in practice -- there's no public process to get any other symbols added.

That omission will likely change. The administration is looking into creating a process to make future displays "more inclusive," Strott said. However, he said, the most common question from the public is not about adding symbols. It's, "'Why is there a nativity scene? Isn't that illegal?'"

There's a nativity scene because...

The city has had a creche at least since the early 1940s, according to court documents. The Denver Post reported that the city erected a massive painted scene of Christ's birth "twenty two feet high and forty eight feet wide" above Bannock Street, a predecessor to the display we know today.

It's a tradition. And as far as we can tell, that's the only reason it's still around.

In fact, if it was damaged or destroyed, Denver would not replace it, Strott said.

Denver's Civic Center holiday spectacles have never solely been about religious symbols.

Today's web of lights that flicker to the beat of blaring holiday music are less controversial. The indigenous man from modern-day Alaska put on display for children's entertainment in 1926? Not so much.

Denverites were celebrating Christmas with gusto at Civic Center well before there was ever a City and County Building.

Civic Center Park was once the site of a dense, urban extension of Denver, which was primarily centered around Union Station after gold was discovered at the confluence in the 1850s. The park and City and County Building we know today were part of Mayor Robert Speer's desire to build a world-class city, which at the time meant taking on a classics-inspired "city beautiful" approach. Denver laid its headquarters' final cornerstone in 1932, well after the park was complete and, according to opinions published in newspapers, frustratingly longer than Denverites were willing to wait.

Even before the City and County Building showcased Christmas cheer, the area was central to Denver's holiday tradition.

In 1925, the Denver Post reported a 90-foot tree, adorned with blinking lights. In 1926, the paper reported the presence of an actual arctic native -- "Ki-kig-yak from Kivalinak" -- who lived at the park for a couple of weeks leading up to Christmas "as a novel treat for the children."

In 1930 the city housed a handful of fawns in the park. Each year, papers reported the city had outdone itself.

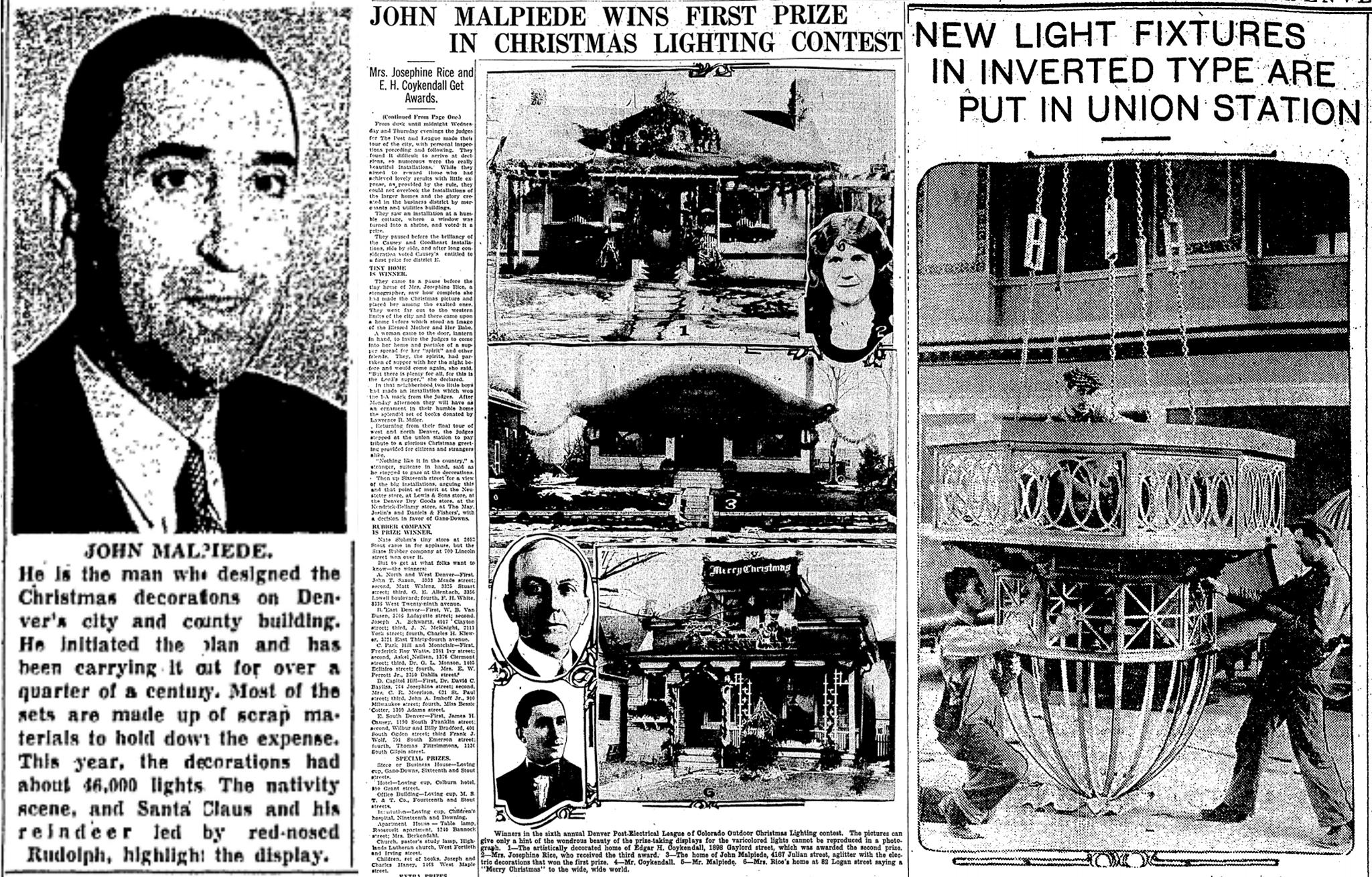

Meanwhile, Denver's city electrician, John Malpiede, had been flexing his Christmas spirit at home -- like Clark Griswold, but competent.

His holiday flare at his house had earned him personal honors, multiple times, as one of the best-decorated in the city. He'd also become the lead technician behind Civic Center's light show each year.

According to one story published by the Post (no date is listed), the light show downtown began in 1914, spearheaded by one of Malpiede's predecessors who wanted to spread some cheer for his dying grandson. According to the story, Denver's outdoor tree that year was "the world's first outdoor electric lighted Christmas display," and the genesis for the city's light show. Malpiede took it over and oversaw it for decades to come.

Through those years, the show was usually reported as being a magnificent sight. Malpiede, the Christmas genius, was often quoted as being behind schedule or without enough resources to deliver the city's growing expectations.

While the presence of a nativity scene was not mentioned every year, it's clear that the holiday's religious core has long been central to Denver's celebration, even if lack of materials made it hard to express.

In 1948, the Post reported Malpiede was nervous about getting it all together: "We've got a beautiful display planned if only the materials come in," he said. "The city has no nativity scene. We never did own one. This year we can't even rent one. We've got a Santa Claus, and I'm going to light him up from here to Pueblo, but we've got no nativity scene."