It's the beginning of the end for north Denver's I-70/Vasquez Boulevard Superfund site.

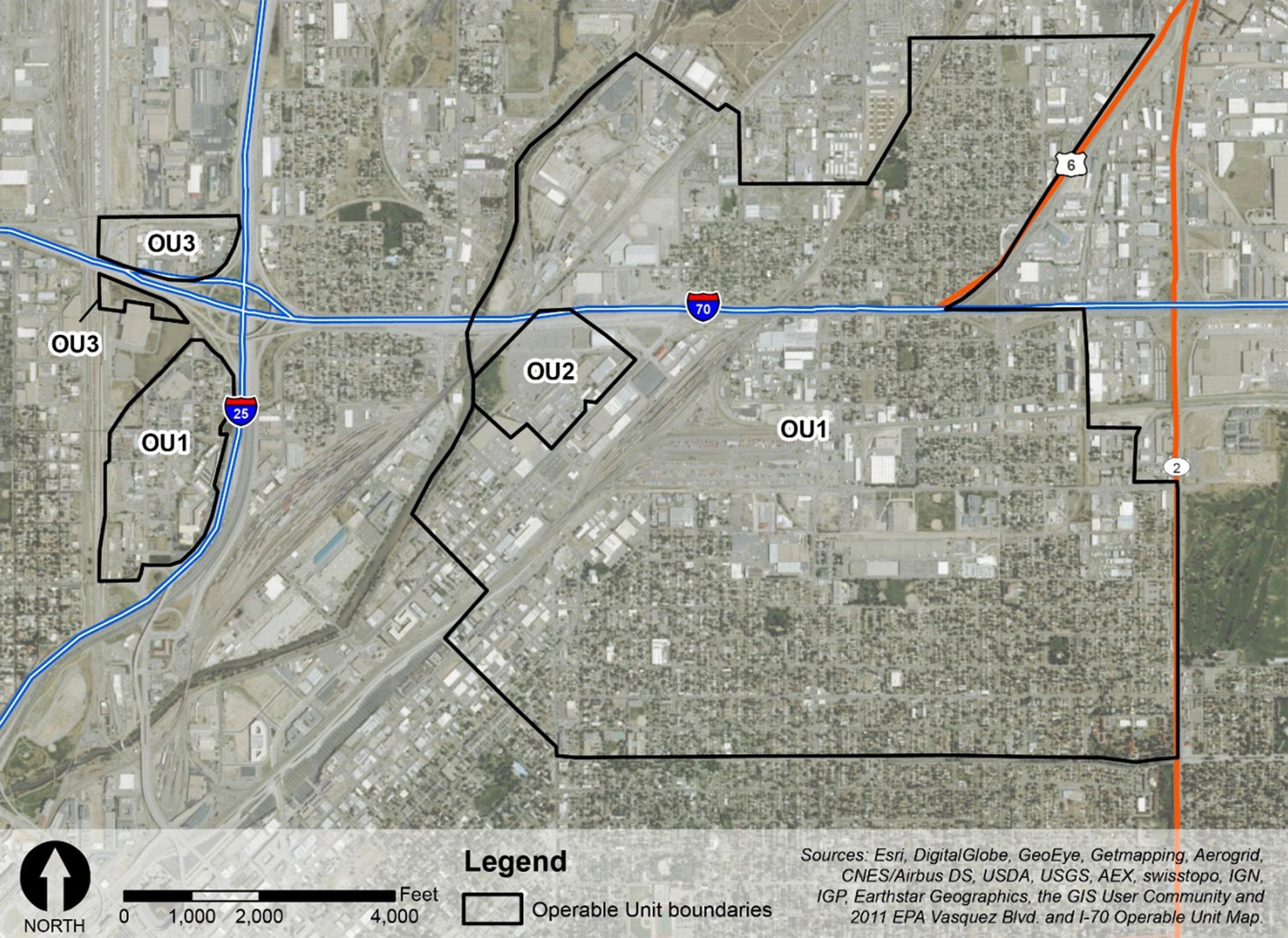

On Wednesday, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) filed a Notice of Intent to Delete (NOID) the site's largest piece, called Operable Unit 1 (OU1), which stretches from the South Platte River to Colorado Boulevard and from Denver's northern border to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Superfund is a federal designation for environmental cleanup, usually for historic pollution when nobody is around to be held accountable. In this case, the pollution in question is lead and arsenic from the Omaha and Grant Smelter, which once stood in the city's northern reaches and closed in the early 1900s.

OU1 is big, but it only pertains to the shallowest inches of residential yards. Most health agencies deal with environmental hazards from the perspective of "pathways to exposure." When the Superfund site was confirmed in 2003, the EPA decided that lead and arsenic in commercial or industrial areas didn't pose much of a threat. The thought was kids might eat dirt at home -- the most likely way they'd get sick -- so only residential areas were included. That decision has been central to community concerns now that those industrial areas are being developed in a slew of big infrastructure projects, in some cases right next door to homes that were remediated.

Over the last decade, EPA oversaw replacement of dirt in nearly every residential yard in the area. They're saying that part of the work is complete, and it's time to remove OU1 from the federal roster of cleanup sites.

Jennifer Chergo, public affairs specialist for the EPA on this project, said the agency pursues deletion when it "determines that there is no unacceptable risk to human health or the environment."

Kim Morse, administrator of a community advisory group for the Superfund site, told Denverite that the EPA's remediation "falls short of protecting human health." Even though the pollution removed from residential yards technically means OU1's very narrow mandate has been completed, she and other neighborhood advocates want to see further action for dirt in nearby commercial and industrial lots and beneath alleyways and roads.

Denver requires that city construction, like the 39th Avenue Greenway project that is digging up soil through north Denver, utilize a "materials management plan" to ensure potentially contaminated dirt is handled appropriately. Even so, people in Morse's camp and neighbors living near north Denver construction sites say they're still not reassured.

The NOID is the first step in OU1's deletion. It initiates a 30 day public comment period before the agency begins to decide if the site should be deemed finished. Chergo said it will likely be a couple of months before the agency files a "final notice of deletion."

This motion was expected late last year, but the federal government shutdown also closed the EPA and caused a delay. Chergo said a possible future shutdown should not affect comments that are sent while the EPA is shut down.

You can get information on how to file a public comment on the EPA's website.

This story has been updated.