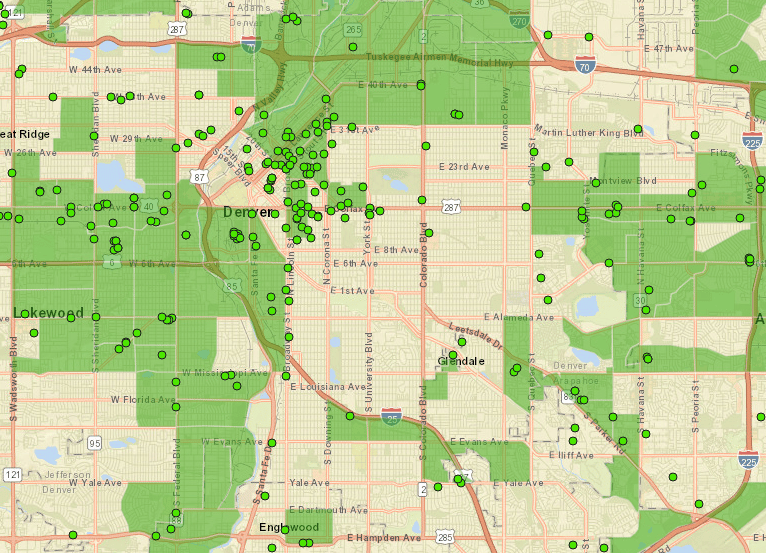

Take a look at a map of affordable apartments in the Denver area and you'll quickly notice what jumped out at Elena Wilken, executive director of Housing Colorado.

"There's some clumping. And some gaps," said Wilken, whose nonprofit's goals include persuading state legislators to create a fund to support the building and preservation of more affordable housing across the state.

Wilken's background is in transit -- before coming to Housing Colorado, she was executive director of the Colorado Association of Transit Agencies. Some of the clumping that drew her eye was along RTD's W Line, which in 2013 became the first light rail service to open as part of the FasTracks plan voters approved in 2004 to expand transit across metro Denver.

The 12-mile W Line connects Denver's Union Station to the Jefferson County Government Center in Golden. Along it have sprung up complexes like Lamar Station Crossing, built by the nonprofit Metro West Housing Solutions, formerly the Lakewood Housing Authority. Lamar Station has 87 apartments reserved for families earning 60 percent or less of the area median income. (AMI is determined annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.)

There's also Arroyo Village, which has 130 apartments for households earning no more than 50 percent AMI. Planners across the country have stressed the importance of ensuring low-income residents who are most likely to use trains and buses get a chance to live near new transportation hubs.

Lamar and Arroyo are among hundreds of little green dots on a state map that is a visualization of a key source of funding for rental housing within reach of low- and moderate-income families. The map shows projects that the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority has awarded federal tax credits since 1986, when Congress created the program to encourage the private sector to invest in affordable housing. CHFA, pronounced "cha-fah," supports projects for households earning no more than 60 percent AMI and generally considers the cost affordable if a household is spending no more than 30 percent of its annual gross income on housing.

What's affordable?

Under CHFA rent restrictions, a Denver family of four earning 50 percent of AMI -- $44,950 a year -- could get a two-bedroom apartment for $1,012 a month. CHFA cites research showing that a Colorado household must earn $52,680 to afford the statewide median rent of $1,317 without spending more than that 30 percent of income.

In policy and development circles, "affordable" is a technical term, usually for housing that is kept below market rates by subsidies perhaps provided by a faith group; government loans; strategies like trusts that take the cost of land out of the equation; or programs like the low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC) administered by CHFA. Sometimes several methods, including renting some units in a complex at market rates as housing or businesses, have to be employed at once to get a housing project built.

To get a sense of the importance of LIHTC, the CHFA-administered program that is usually pronounced as "lie-tec," just try to reach an affordable housing developer around the time an application deadline is approaching. Every state has its own agency distributing the tax credits supplied by the federal government in a competitive process that takes into account need and other criteria.

Here's how it works: Developers who are awarded credits sell them to investors for cash they can use to build, allowing them to borrow less and, because those costs are lighter, charge less in rent. CHFA also distributes state tax credits under a state affordable housing program. Some projects get state and federal credits. Under the program affordability is protected for decades. Lamar Station for example, built with tax credits awarded in 2012, must keep rents affordable for 40 years. Longevity and affordability have been in the news lately because the clock was ticking on about 2,000 city-subsidized apartments in Denver. Last fall Denver City Council voted to extend the minimum that city-subsidized housing had to stay affordable from 20 to 60 years.

Some developers will try year after year to get tax credits from CHFA, without which projects often cannot go ahead. CHFA takes into account such issues as the developer's experience, the need for the proposed project and whether it's close to public transportation, financially viable and allowed by local zoning.

Where does affordable housing go -- and where does it not go?

"There's no area that's off-limits," said Jerilynn Martinez, CHFA's director of marketing and community relations.

Proposals for LIHTC projects in what are known as Qualified Census Tracts, which are areas the federal government has designated as being in particular need, may be eligible for additional tax credits.

None of the green dots denoting a low-income housing tax project appear in, say, Cherry Hills Village or Cherry Creek. Or Hilltop or Crestmoor Park, identified as no places for affordable housing by one resident speaking to the Planning Board earlier this year during a spat over a zoning exception. The resident went on to advise that "you can go one block south into Glendale and there you have affordable housing."

And indeed the CHFA map shows Forest Manor Apartments in Glendale, with 103 units for tenants earning 60 percent of AMI that were to remain affordable for 20 years when tax credits were awarded in 2001. An interested user can click on the CHFA map to zero in on metro Denver projects.

Developers pick their battles.

"The most important thing I think is finding neighbors or cities or communities that recognize they have a need for affordable housing. If you can get that as a base, it's easier to get sites," said Dick Taft, whose private nonprofit Rocky Mountain Communities has been building and preserving affordable housing in the Denver area and elsewhere since 1992.

Taft added rising land costs have made the task of finding sites even harder. He's taken to redeveloping sites already in his company's hands, as was the case with Arroyo Village. There, he razed not only an aging Rocky Mountain Communities development but partnered with his neighbor, the Delores Project, to take down an old shelter for people experiencing homelessness. By pooling their property the two nonprofits were able to build a new shelter plus a 35-unit supportive apartment complex that Delores will manage for people who have been homeless and earn less than 30 percent of AMI and 95 apartments that Taft's company will manage for people earning no more than 50 percent of AMI.

Corrects previous version which did not include an affordable complex in Glendale. The error, due to this reporter's poor map-reading skills, was spotted by a keener eyed reader.