District 9 is Denver's engine of change.

It's where Union Station anchored unprecedented growth that has since rippled outward, supplying more places to live and experience.

Denver's unhoused population is most visible here, as are the outward signs of gentrification -- new homes and businesses supplanting and intermingling with old ones -- where sudden investment has attracted new people and pushed out others.

District 9 is where you'll find the most robust pieces of Denver's transportation system that don't bow down to the automobile: Frequent (sometimes free) buses and trains, bike lanes physically protected from traffic, and compact, walkable areas.

Yet you'll also find plenty of parking lots, construction blocking paths for walking and wheeling, and residents bracing for the widening of I-70 through their predominately low-income, often Latino neighborhoods.

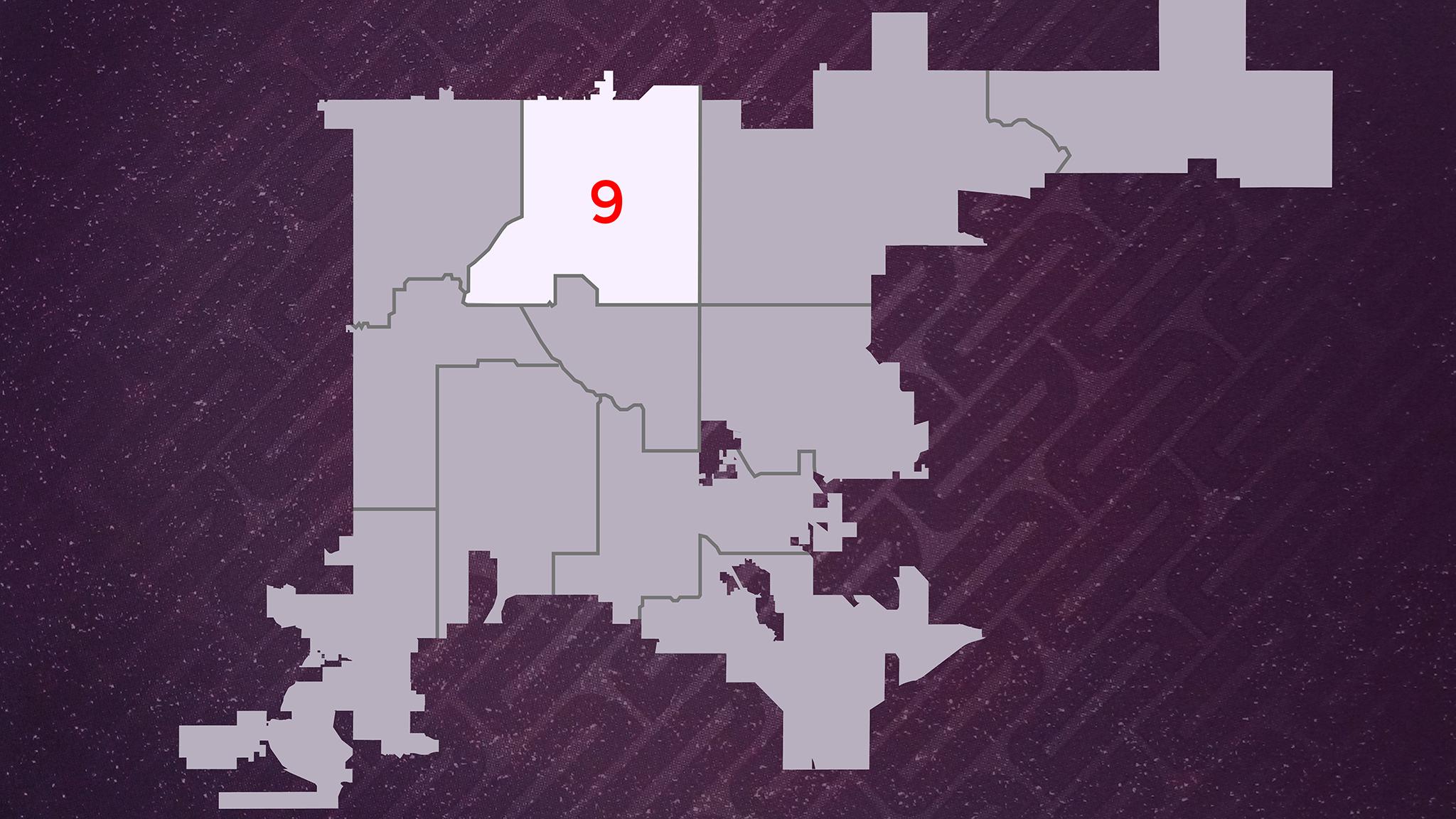

Four candidates are looking to rep District 9, which houses the Central Business District and Five Points (including the RiNo Art District) and stretches east to Whittier and north to Globeville, Elyria and Swansea:

- Albus Brooks, the two-term incumbent city councilman

- Candi CdeBaca, a civic activist and executive director of Project Voyce

- David Oletski, a Globeville resident and neighborhood activist

- Jonathan Woodley, a sergeant in the National Guard

Albus Brooks

Brooks often calls himself an "urbanist." His top issues are housing, homelessness and transportation.

He believes that cities work best when there's a diversity of businesses and housing types -- apartments, condos, single-family houses, four-plexes -- in a diversity of neighborhoods for a diversity of incomes. In his book, these things should be connected to the rest of the city by convenient transit and biking options, and situated close together so people can walk to the places they need to be (aka density).

In an interview, Brooks, a councilman since 2011 who beat cancer twice while in office, said his wins span various arenas. But his focus is on housing and urban development.

Brooks helped establish the city's first affordable housing fund, for example, and has seen the construction of more than 5,200 attainable homes in District 9, according to the Office of Economic Development. That figure does not account for the number of affordable homes lost to higher property values and redevelopment, however.

The councilman says displacement from gentrification in his district is a result of a long-entrenched systemic failure, not a direct result of his governance.

"From 2000 to 2010, 80205 was one of the top gentrified zip codes in the country," Brooks said. "I was elected in 2011, and so we're fighting a 30-year battle and have really been implementing only in the last five years. We need to continue on this trajectory of putting policies in places where it includes everybody."

Lately, Brooks has been promoting the Beloved Community Tiny Home Village for previously homeless Denverites. Globeville residents, who have felt stepped on by city projects for years, recently blocked the community from moving to their neighborhood.

One reason they're distrusting: the Colorado Department of Transportation's I-70 expansion through north Denver, which Brooks did not fight, displaced residents and will add cars to an area long polluted by highway exhaust.

"We need to put our focus on the continuum of housing -- the tiny homes, the prefab housing, the transitional housing," Brooks said. "On all of our vacant lands, we really need to be focusing on some of those issues."

The former city council president says he's proud of a policy he birthed that lets developers add height to buildings near the 38th and Blake RTD station if they include affordable homes. (His opponents don't like it.)

On homelessness, Brooks authored and still supports the controversial urban camping ban, which lets authorities remove people and their property if they're sleeping on the street.

"It is inhumane for us as a society to allow people to sleep in public spaces," Brooks said.

"It's unfair that we said we're gonna end homelessness in 10 years. This is a federal systemic problem -- we don't have enough funding for our mental health, we don't have enough funding for our housing issues, and so this will always be a problem for cities to solve."

If re-elected, Brooks will ask voters for funding sources to prevent homelessness and work to add shelter space. He will ask the mayor to open up rec centers and religious institutions for overflow, he said.

Brooks is a self-described advocate for sustainable transportation modes like transit, walking and biking. He's interested in the city taking over RTD lines within city limits to make the bus system fluid and convenient, he said, and asking the voters to fund those improvements and others.

Candi CdeBaca

CdeBaca is a fixture in District 9 because she's lived in Swansea most of her life. She led the fight against CDOT's I-70 expansion and runs Project Voyce, an organization dedicated to engaging kids in civic life.

She wants some of the same things as Brooks -- walkable, transit-rich neighborhoods and more services for people without homes -- but doesn't agree on how to get there.

Her top issues are housing and wages, traffic and pollution, and accountability and transparency. She couples those things together because you can't have one without the other, she said in an interview.

The first-time candidate is a vocal critic of Brooks, who she says short-sells neighborhoods when it comes development. For example, she says Brooks' building height incentive is a bad deal for Denverites.

"In the midst of a housing crisis, leadership is about demanding more and the 38th and Blake overlay was a complete giveaway to developers, calling itself a housing solution," she said. "The affordability 'incentive' is unlikely to be utilized as the upzone is substantial enough without the height incentives, and the most we can expect of the entire rezone is less than 100 affordable units."

Denver can't build its way out of the housing "crisis," CdeBaca said. Displacement will only drop and affordability will only rise if government policies undercut the profits of private companies, she said. That's what she tells voters around the neighborhood.

"What I have to do is convince them that it's an engineered condition engineered by policy -- policy that uses land and zoning in a particular way, policy that allows us to increase taxes in a way that destabilizes community, policy that disallows innovative and creative forms of co-housing and cooperative living," CdeBaca said. "So because this condition is created by multiple policies, my policy goals are to really get in and change those policies.

"One of the things that makes me unique in this race is that I've spent my career studying root causes of our problems, as well as writing policy and researching policy," CdeBaca said. "The root cause of our housing crisis is not that we don't have enough housing. The root cause of our housing crisis is that we commodify housing, and we commodifiy housing because of our economic system, which is capitalism."

If elected, CdeBaca said she would undo the "linkage fee" developers can pay in lieu of building affordable units. Instead, she would reinstate and strengthen Denver's inclusionary housing ordinance, which would force homebuilders to build a certain percentage of attainable units. She would like to see a percentage much higher than 10.

CdeBaca says high taxes -- property and otherwise -- destabilize neighborhoods. So she'd work to restrict tax increases in a given cycle. She tossed around the idea of no more than a 10 percent hike in two years.

Denver's myriad plans, like its housing plan and its transit plan, are more like "visions," according to CdeBaca -- they don't lay out enough actionable steps. She wants sidewalks. She wants high-quality transit. To get that, she will look at charging major developers and corporations an "impact fee" to pay for housing needs and infrastructure.

"I think right now is the best time to tax the big builders, tax the corporations in a way that creates the padding for us to execute the plans," she said.

In her mind, District 9 is bearing the brunt of development. She wants to see other neighborhoods absorb their fair share of impacts on infrastructure, traffic and pollution.

Her fight against CDOT's I-70 widening is one example. Another is a grocery store and 200 homes that her opponent, Brooks, helped solidify. She says the development is overkill and will strain the community.

David Oletski

Oletski and his family are long, longtime residents of Globeville. His family has lived there since the 1800s.

An activist who's ingrained in the north Denver neighborhood, Oletski has spoken out about lots of things, most recently the Beloved Tiny Home Village for unhoused residents that Councilman Brooks and the Hancock administration wanted to relocate to city property in Globeville.

He did not welcome it. Oletski called the village a "glorified homeless camp."

The longtime volunteer for Groundwork Denver and Habitat for Humanity was instrumental in getting the ball rolling on turning a dumpy, polluted field at 49th and Grant into a park. He was also a neighborhood voice in the redevelopment of a defunct smelter in the area, according to his biography on Groundwork's website.

Oletski has not returned requests for an interview, but we'll update this story if and when he does.

Jonathan Woodley

Woodley, a sergeant in the National Guard, lives in the Central Business District. After he came back from the Middle East in 2017, he did not recognize his city.

"When I came back to Denver I realized I wasn't in the same city that I had just left," Woodley said. "I noticed that we have new buildings and everything, and that was fine, but I feel like I didn't realize things were going on while I was here."

Specifically, Woodley believes he was witnessing "social genocide," which he described as the government propping up development for profit's sake, rather than for the sake of residents.

"What I saw was a type of oppression that was different than what I just came from," he said. "And what I mean by that is, if you weren't making a certain amount of dollars, you were pretty much discarded, displaced and the local government really didn't care about you."

Denver has services to care for residents, of course, but Woodley says they're outweighed by greed. Developers can (and do) pay a fee to the affordable housing fund in lieu of building the units themselves. Woodley called that practice "public bribery."

As a councilman for District 9, he says he would at least double the linkage fee. He would ease restrictions on developers simultaneously, to make building affordable housing easier, he said.

On homelessness: Woodley is not against the urban camping ban, but he's not for it, either. He believes there's something between kicking unhoused people off of the street and letting them live on public sidewalks.

The candidate has a three-tiered approach to solving homelessness, he said. First, provide way more housing -- shelters but also actual homes, like the tiny home village. Next, offer everyone services, like job training and mental health aid. Finally, he would help people reintegrate into society, which he compared to the three months soldiers get when they reenter civilian life.

Of course, these aren't new ideas, but Woodley thinks he has the gumption to make them happen. Brooks, he says, does not.

"I helped liberate half a city," he said. "That's changing a city. Heroes don't wear Gucci shoes."

Who's got money?

Here's how much the candidates have raised, according to the most recent campaign finance report. Click on the candidate's name to dig deeper into who is giving them money.

Brooks has raised more than $220,000.

CdeBaca has raised about $57,000, including in-kind donations and about $4,600 in loans.

Woodley has raised about $2,100, most of which consisted of contributions to himself. Woodley is not taking donations from special interest groups, he said.

Oletski has not filed a campaign finance report.