Artist Jonathan Saiz grew up in the Denver area and once dreamed of seeing his work in the Denver Art Museum, "a temple in its own right" in the city he's left and returned to many times since he began his professional career.

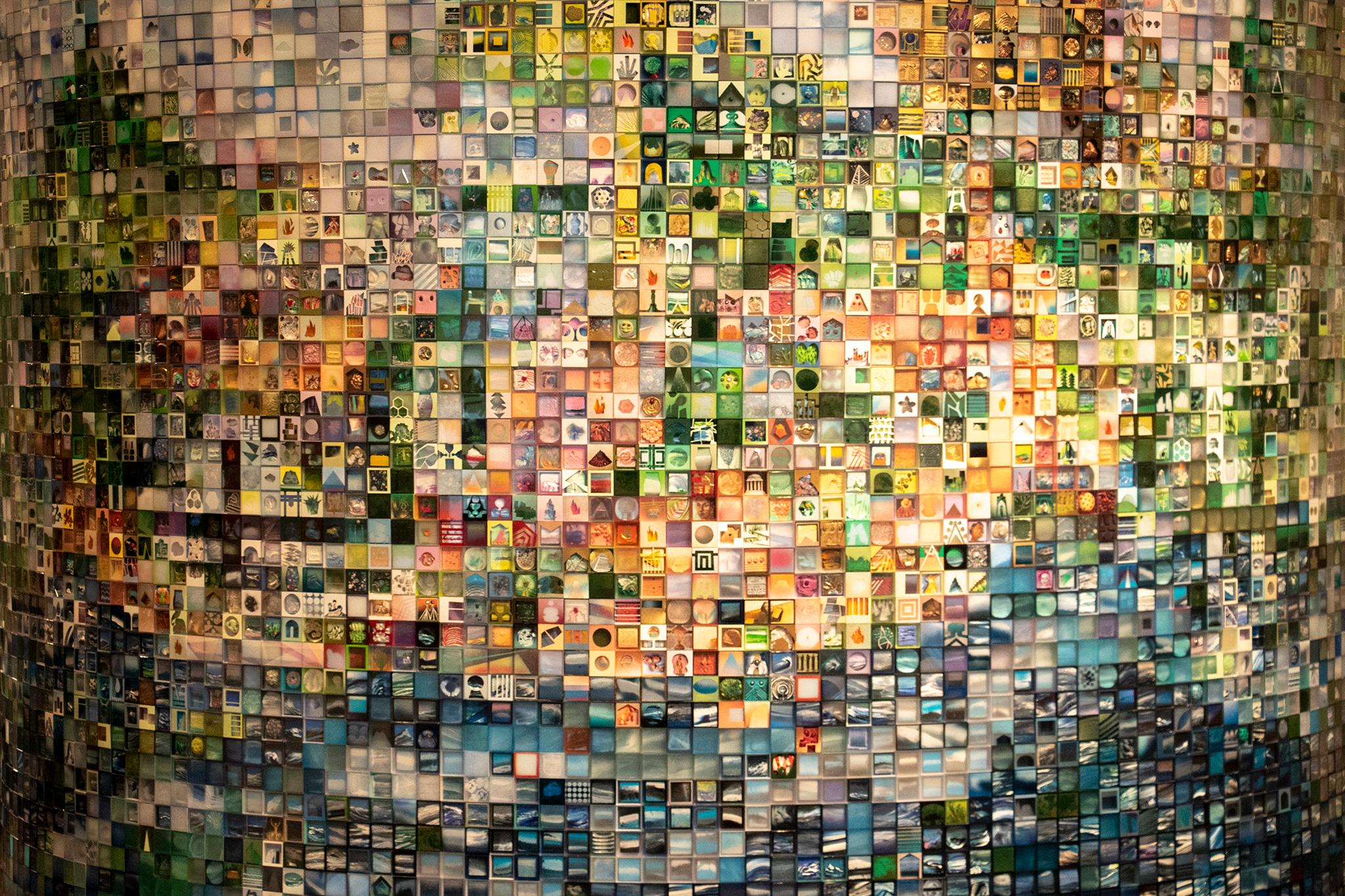

He was beginning to explain his first installation at the museum, titled "Study for Utopia," when visitor Miriam Williams felt moved to speak to the artist. She'd already been captivated by his work, an eight-foot column dense with 10,000 tiny paintings.

"I have a question," she said. "How many years-"

"150 days," he answered before she could finish.

"10,000 in 150 days?"

"Yeah," Saiz said, "so I've been very, very, very busy."

"I bow to you sir," Williams replied, "not only your creativity but your dedication, because I can't even imagine how you did that much work in such a short span."

And then, the kicker.

"You know what helps?" Saiz said to her. "Knowing that I'm giving them all away for free at the end."

"You're going to deconstruct this?" Williams asked.

"Yep. This just becomes property of 10,000 different people at the end. For free."

"What can I say to you?" Williams replied. "You're giving me chills. You're literally giving me chills."

So, you're not alone if you're throttled by the idea of owning one piece of Saiz's massive collection of paintings. He is, too, after all.

"Study for Utopia" is an exercise in collective ownership, something Saiz and museum curator Becky Hart began talking about more than a year ago.

Hart said it's the first time a museum artist has ever distributed work for free at this scale, and it's right in line with their mission.

"We're a public institution that's publicly funded, so in a sense, every Denverite should have a sense of ownership and pride in the institution," she said. "But to actually be able to have a physical manifestation of that, have something to take home, is really very different than to have the artworks that are contained within our buildings."

For Saiz, the work is part of a quest to define utopia, some kind of perfect world that can only exist if we pull away from our society's tendency to over-value objects and hoard wealth. Art can be a commodity for the wealthy, so it may feel distant to average people.

"[With this piece], people could walk away feeling like contemporary art is really for them," he told Williams. "I mean, how few people are going to own a piece in a museum? It's very emotionally separate, so I was excited about changing that conversation."

The installation and giveaway are exercises in challenging art as an economic system. The fine art market, Hart said, is a place with "unreal" values that are not based in "the world you and I live in." Its emphasis on value and scarcity is one reason it can be so isolating.

"No one can come in and say, 'I like this pretty sparkly thing. I want it for myself. I'm going to squirrel it away in my dining room or, worse, my insurance vault,'" Saiz said. "The work only exists once in its totality and then lives off as seeds. So this is the very first iteration of a much bigger project. The fact that it doesn't have to be preserved, it doesn't have to be insured, it doesn't have to be protected, it can't be owned, makes it more ideologically related to utopia."

Challenging economics and value is also the reason he's included real gemstones and even a family heirloom, a wedding ring, in some of the tiny 2×2 inch pieces.

"In the 1970s my dad proposed to my mom with that ring, and then it sat in his underwear drawer for 30 years," he said. "I think that's a great reminder of how much wealth is squirreled away in the world that isn't being utilized."

This idea extends beyond just the ring itself. Saiz pointed to the entire business of extracting gold, the fact that people "are dying" to supply global demand is a sign that the world is leaning towards dystopia.

Embedding the ring in art might protect it from being subjected to any more underwear drawers. It has new value as a unique piece and as one of many symbols for a utopia, a better way to live.

"I wanted 10,000 different versions to be possible to people," he said. It's "something to start to think about what they personally would do to make the world better."

Not every viewer may pick up the full depth of his purpose behind the installation. Some may just be enthralled by each individual motif or the swaths of color when viewing the column's mosaic from afar.

"The message is more complex and has a lot more to do with economics and all that, but the visual sparkle factor is really high, and I did that on purpose," Saiz said. "It's fun to watch people walk by and see it sparkle and glimmer and explore."

Saiz's full installation will be on display at the Denver Art Museum until November. They're still figuring out how the giveaway will work, but Saiz said to follow the project on Instagram to stay in the loop.