Hand in hand with Denver's housing crisis come issues of hunger.

Across the city, Denverites are working on food insecurity and food justice. As we did in the areas of housing and politics, we wanted to know who those people are -- particularly the people who are just beginning to make a difference or have promising things on the horizon. From your nominations, we pulled these 10 people.

Come and meet them from 6:30 to 9 p.m. June 6 at Comal Heritage Food Incubator, 3455 Ringsby Court, #105. We'll eat some food, drink some drinks, and talk about Denver's hunger issues. You can get tickets here.

Right now, you can get to know them here.

Denver Food Rescue Executive Director Christine Alford started her current role in April after starting a full salaried position with the food rescue last fall. She's been part of the nonprofit for about fours years and first came in contact with them as a participant in 2015 when she sought their services to help feed her family. She now helps oversee 18 no-cost grocery programs.

The role gives her a chance to enact policies addressing concerns like proper nutrition, food insecurity and food deserts throughout the city. She started her own no-cost grocery program in Five Points before joining the nonprofit's board of directors and later earning a job as a program director last fall. Her biggest goal now? Motivating other people, just like the nonprofit motivated and empowered her when she was in need.

"Communities are the muscles of organizations. Without communities and without their voice, and us leveraging that connection, there's no way for us to really see the impact or get the feedback from them on what is needed out there," Alford said.

Paola Babb went to school for nutrition and she's using that knowledge to help her run the food pantry at Westminster's Growing Home.

She was nominated in part because she knows people are what they eat, and she instituted a model that disperses a nutritional combination of foods to each family or individual.

Babb was also nominated for her impeccable organizational skills. When Babb came onboard, the pantry needed structure. She created an experience that was more like a grocery store, giving people choices they don't always have with hand-ups. And she instituted a rationing system that looks ahead to ensure tomorrow's families don't go hungry in order to feed today's.

Last year the pantry rarely served more than 300 people per month. This year, it's the rule, not the exception.

"It was already a great program and now it's just been improving and getting better," Babb said. "I have drive and passion for the families we work with, and so do my colleagues, and with my background and everything, I hope to implement more."

She couldn't do what she does without the help of her colleagues, Babb said, or the families they serve in the "participant-centered" model.

Kate Mishara began teaching first grade at Cole's Wyatt Academy 10 years ago, but eventually found that her passion centered more on helping students and families overcome barriers to learning. Namely, hunger.

As the school's director of community engagement, Mishara launched a "free grocery" at the school that helps students and their families at a school in which 94 percent of kids qualify for free and reduced-priced lunch. The school is also in a food desert.

"We really believe that targeting hunger insecurity meets a direct need for our families, but also meets a larger goal of setting our scholars up for success every day at school," Mishara said. "We know if kids are hungry, they are not going to be able to bring all off their excitement and focus and energy to the classroom."

Nonprofit partners and the families themselves make the program work. It's been so successful, Mishara is looking to scale up.

"Our next step is to figure out how to expand and meet the needs of our broader community, because the model is working really well ... and we know the need extends outside of Wyatt."

Alicia Perez is the Community Outreach Coordinator at The GrowHaus, a position she earned after first getting involved in the program as a Denver high school student in 2011. The program works directly with the community by distributing thousands of pounds of food "rescued" from local supermarkets and farmers markets. They have three indoor farms and offer food education programs.

"I feel that that place really serves, directly, the community," Perez said. "We serve directly to help then support them with education or food. We also help them with different resources; so if we don't have the capacity to serve them with paying for their electricity bill, we send them somewhere else."

Perez also works in the Promotora program, which primarily helps women in the community who live in food deserts, including neighborhoods like Elyria Swansea and Globeville. In her role, she helps train others to teach the kind of classes GrowHaus specializes in, as well as how to make home visits to teach people more about gardening and nutrition. They also teach classes on herb and traditional medicine, so families can learn about homegrown remedies.

Arlan Preblud started We Don't Waste about 10 years ago, and has scaled it from an operation that once relied on his Volvo station wagon to a three-truck enterprise with an 11,000 square-foot distribution center.

Preblud began the nonprofit by asking restaurants and caterers for unused food, and delivering sustenance to Denverites. Now he gets grub from huge commercial vendors, like grocers who won't put food that expires in a week on the shelves.

It's a one-two punch that feeds about 180,000 people a year -- 10 million meals -- while keeping would-be waste out of landfills.

Next, Preblud is taking the operation mobile. With his mobile food market, he will ferry sustenance to food deserts for families without transportation options, instead of asking them to come to him.

"If you don't have food in your belly, it's really hard to concentrate on anything else in life because you're worried about when and where your next meal comes from," Preblud said. "If you're a young child, it's difficult to get on a school bus and go to school while your stomach is saying, 'Hey, I'm hungry,' and the teacher's up there telling you to concentrate. So it's fulfilling in so many different ways."

Jack Regenbogen is an attorney and policy advocate for the Colorado Center on Law and Policy, which aims to create economic security for everyone in the state, not just the wealthy.

His claim to fame in a space with few celebrities is using the law to give more Coloradans access to SNAP, or the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program -- the credits once known as food stamps.

Regenbogen's expertise helped people without homes keep their food assistance, even if they're not enrolled in a state work program, which was once a requirement. The goal was to keep people fed even if they could not always work.

Next, the attorney will tackle SNAP overpayments. If Colorado mistakenly disperses too much money, they can force recipients to repay that money long after it's spent.

"We're trying to suggest a more reasonable statute of limitations so that clients don't end up with this crushing debt and tens of thousands of dollars that they'll never be able to pay back," Regenbogen said. They could get kicked off SNAP with kids. They might have their SNAP benefits docked or they will have their taxes. In some cases, they'll have their wages garnished."

Ricardo Rocha, CEO of the low-cost food delivery service Bondadosa, is a DREAMER who found his calling for the community while studying pre-med at MSU Denver. He wanted to work in Latino advocacy.

So he focused on minority communities, specifically the ones he felt seemed to have easier access to cash advance places and liquor stores than fresh groceries. He knew the importance of proper nutrition in helping avoid illnesses like hypertension. So he started the food delivery in March 2017 with Denver Food Rescue and now works with local farmers, growers and grocery stores to deliver food directly to people's homes. He started by delivering food on a bike before switching to an electric car. They now make about 350 deliveries a month.

"We envisioned a more robust, more sustainable, more local kind of Colorado food ecosystem," Rocha said. He said he wants to, figuratively speaking, look into people's fridge to ensure they have a chance to succeed. "Those are the people building our future."

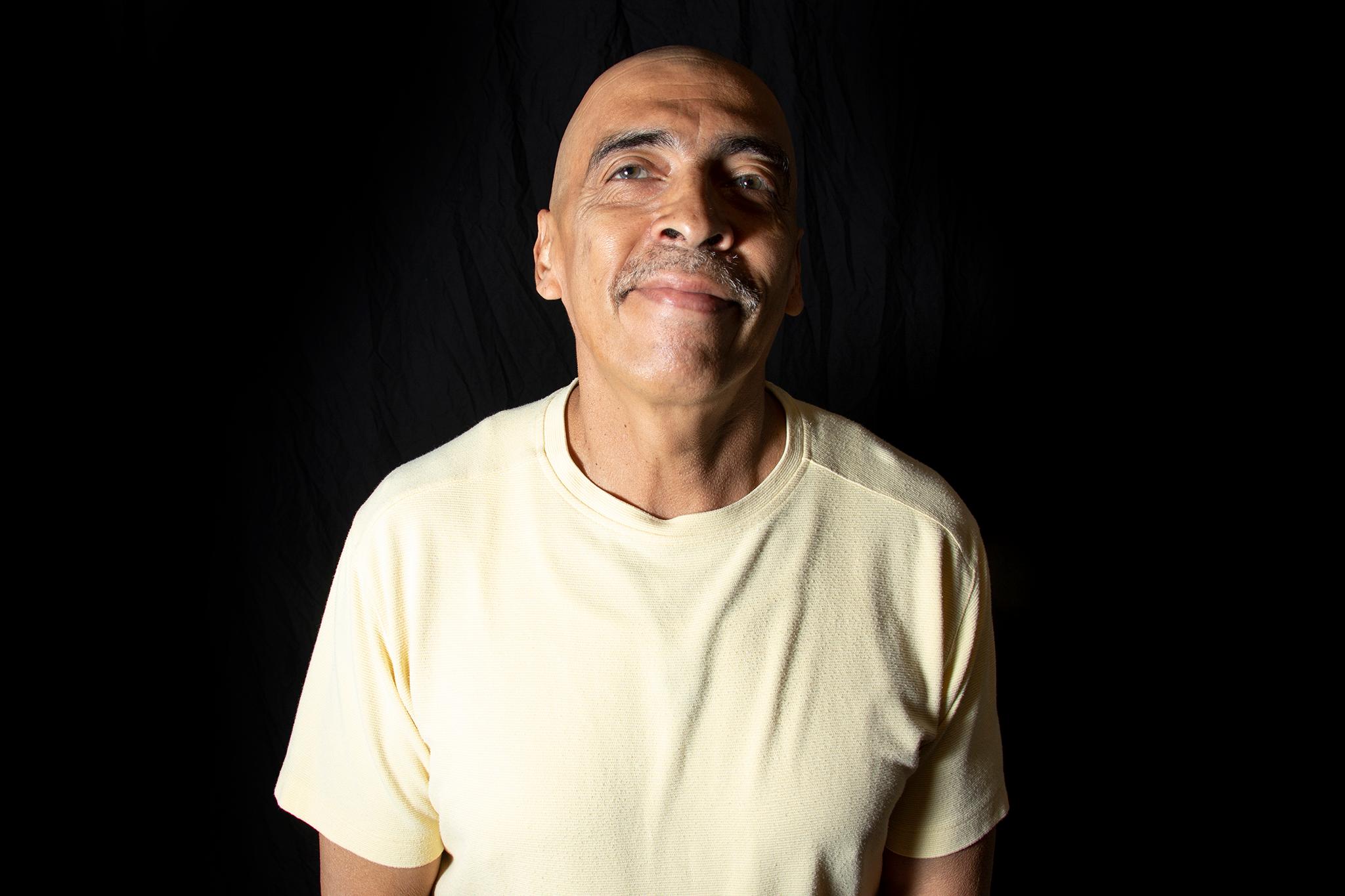

Donicio "Dennis" Romero works with the Volunteers Of America overseeing the Sunday Lunch Bunch Program. The program provides 250 lunches to people without homes in Denver with help from 14 area churches, who supply the food and alternate weekends to provide the lunches. The lunches are delivered to the Volunteers Of America offices on Lawrence Street and handed out throughout the week.

"The reason I'm doing this is I feel like it's my passion," Romero said. "It's something that I've been called to do. I don't like to see people go hungry."

After taking over the program in November, Romero is working on expanding it to provide more meals. He's hoping to get at least 250 more lunches every weekend and has been asking other area churches to help out with the additional lunches (he drafted a letter with more info on how to help). He retired four years ago but has worked with Volunteers Of America since 1988. Back then, he would hand out coffee and sack lunches with his mother from a table set up near Stout Street.

Lucy Roberts is a school nurse at Manual High School, but she's added a new role to her job description: food pantry manager. It's an out-of-the-box role she slowly grew into when she first started working as a nurse five years ago. At the time, she noticed kids coming in with symptoms suggesting they weren't getting enough food at home.

To help provide more nutritious food options, she reached out to Manual alumni to help. Three years ago, the idea that began inside her office morphed into a full food pantry called the Bolt Bag Food Pantry. It recently secured a partnership with Food Bank of the Rockies, making the program sustainable and able to provide more meals and snacks for students and others in the community. Her work has helped hundreds of families in the community.

"I think my biggest motivators are the kids that come down and some of the parents who have come through and the support that I've gotten from my school itself," Roberts said.

Teva Sienicki runs Metro Caring, but in a way, she would love to put the food pantry and community center out of business.

"Are we interested in putting a Metro Caring on every corner? No," Sienicki says. "We're interested in shortening the line and reducing the demand for services like Metro Caring."

The key to reducing that demand, she says, is by attacking hunger as a systemic problem, not a one-off issue.

That's why Metro Caring is more than a free food pantry with ample, diverse options that restores people's freedom to choose. It's a place where locals can garden -- there's a hydroponic farm in a shipping container -- and learn to cook, or get enrolled in government benefits for food security, to name a few things.

Sienicki aims to keep Metro Caring on its current "systems-based" trajectory, a model she says is gaining popularity in the space.