Dining room hours were once strictly observed at the converted nursing home on a leafy stretch of Federal Boulevard where the Salvation Army has for three decades housed and supported families experiencing homelessness. A curfew and rules about when residents were supposed to vacate common areas also were in place.

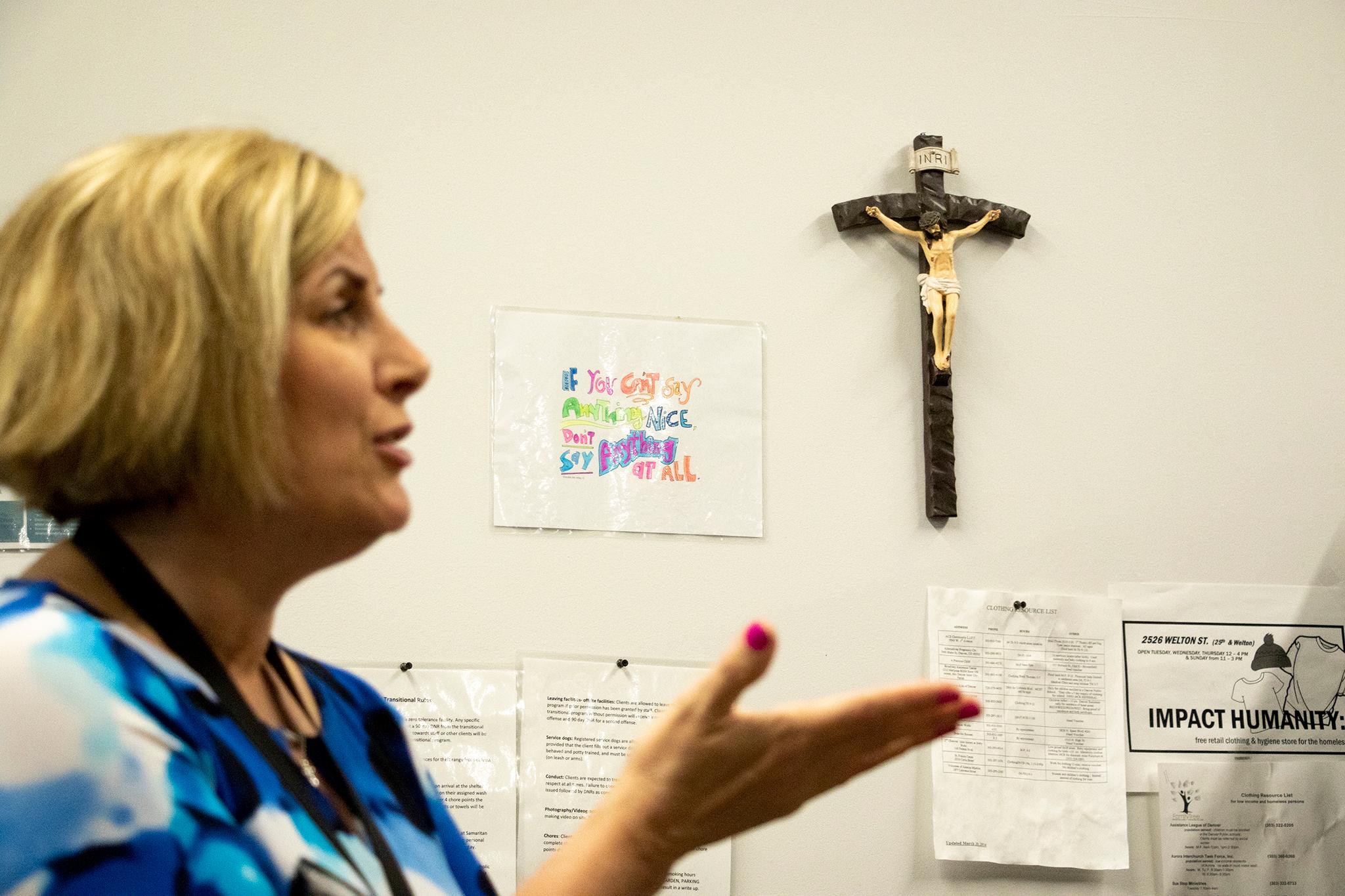

Such regulations have been relaxed in recent months to accommodate, for example, parents whose work schedules keep them out late. Kristen Baluyot, who oversees Salvation Army family services, said the shift from structure has been part of an overall rethinking of operations at Lambuth Family Center.

"We used to have a lot of rules," Baluyot said. "Now, we've eliminated a lot of those rules."

"It takes a long time to change staff culture and change beliefs about homelessness. Even among people who are serving the homeless."

As comments at public meetings about housing and homelessness in Denver attest, beliefs about who ends up on the streets also are entrenched among the general public. Take a recent gathering to discuss tiny homes as a shelter alternative in Clements, near downtown. A woman said with firm conviction:

"The people who are in this neighborhood who are homeless are drug addicts."

She suggested that money be spent on addiction treatment programs, not tiny home villages.

Getting beyond either-or thinking can better inform how both service organizations are run and policy decisions are made.

Because homelessness has many faces, addressing the crisis requires more than one approach.

The Denver Foundation commissioned a 2015 poll that measured understanding of homelessness among registered voters in metro Denver. The picture of a typical person in homelessness drawn from the survey's responses is narrow: a single man who was likely unemployed and struggling with substance abuse or mental illness. The survey helped spur an effort by the Denver Foundation to raise awareness about the complexities and breadth of homelessness and encourage action, in part by helping people who have experienced homelessness tell their stories.

Stephanie Miller, CEO of The Delores Project, summed up the stereotype that the Denver Foundation's storytellers are trying to shatter:

"It's somebody who has all these challenges and doesn't have the drive, the motivation to better themselves," Miller said. "I hate even saying these things because it's so contrary to what's really happening."

The Delores Project has long run a shelter and recently opened a permanent housing project. The women and transgender individuals Delores serves and the families at the Lambuth Center often don't figure in conversations about homelessness. Neither are older people, whom services providers are seeing in increasing numbers. Miller said The Delores Project recently sheltered a 94-year-old woman. The elderly are often on fixed incomes that have not kept up with metro Denver's fast-rising housing costs.

The Salvation Army's Baluyot said: "Homelessness can mean both parents are working and they're still facing homelessness. It can mean someone was sick, lost their job and are homeless even though they were perfectly stable for years."

Ending up on the streets can leave people feeling they have failed, Baluyot said.

"It's oftentimes the greater system that has failed them," she said.

Two-parent families with children. Single parents. A household formed of grandma, mom and the kids. They're all realities of homelessness, said Megan Newton, Baluyot's program manager at Lambuth Family Center.

The people who try to literally count people experiencing homelessness say even their count is too low.

The point-in-time survey is an annual attempt to gather numbers and details about homelessness. But the strict definition of homelessness used in the survey doesn't, for example, count people sleeping on the couches of friends and relatives, a precarious living arrangement to which families who have lost housing often resort.

The point-in-time does give a rough portrait. A not insignificant number of people who speak to point-in-time surveyors describe symptoms of severe mental illness and chronic substance abuse. But they are far from the majority. A large number of families, many with children, are counted year after year. As are people who are fleeing domestic violence.

A disheveled man -- eyes wide with pain or drugs taken to mask pain -- stands on a street corner holding a cardboard sign on which he's scrawled a plea for help. He's obvious. We don't see others experiencing homelessness because they are hiding. Women experiencing homelessness can be fearful of being tracked down by an abuser or being victimized again.

Cheryl Talley, director of communication for Catholic Charities in Denver, once met a woman who spent her nights huddled behind a dumpster. Other women try to get vouchers they can use for a night or two in a hotel.

"If they're lucky enough to have a car, that's where they'll spend the night," Talley said. "They're much more apt to be in places where they can't be surveyed, because they choose safety."

Because of the safety concerns of some of the women who spend nights on cots arranged on its concrete floor, Talley asked that the address of the Catholic Charities emergency shelter for women not be publicized. Women gather in the evenings at Samaritan House, a Catholic Charities service center downtown, where they are given dinner before being taken by bus to spend the night in a nondescript office building in an industrial part of town. Pets are allowed, which is unusual for a shelter. Talley said some women depend on pets for security as well as companionship.

During winter, it's not unusual for 200 or more women to spend the night at the Catholic Charities facility, Denver's largest emergency shelter for women. The same building hosts a separate, 50-bed transitional housing facility where women can stay as long as they need.

The transitional facility looks like an unusually large dorm room, with beds personalized by bright comforters instead of the cots in the emergency shelter. In one corner, sofas are arranged in a conversation pit. Lockers provide a place to store belongings safely when women are out working or looking for jobs or housing. A bulletin board near the entrance.

Some women have been able to leave to go to permanent housing. Others might stop first at a more structured program, such as those run by Catholic Charities at Samaritan House or the Delores Project.

"Because there's such different needs, everybody (service providers) almost has to have different slants," Talley said.

The Salvation Army has found it can serve more people by being flexible.

Its Lambuth Family Center opened in 1987 as a structured program that served families for up to two years. After a restructuring that included a renovation, it reopened last December as a 90-day program focused on first getting families into housing, where they could have the stability to work on issues that might prevent other successes. In some cases, all that needs to be fixed is a lack of housing.

"Housing is our No. 1 thing," Baluyot said.

Between December, when the program change took effect, and May, 37 families have been served at Lambuth, and 20 of those have moved on to permanent housing.

"I found as a transitional housing facility, the longer people stay, the harder it is to leave," Baluyot said. Before switching from two years to 90 days, a shift she discussed with staff for some two years before implementing, "we weren't serving nearly as many families as we are serving now, and we weren't seeing as much success."

A sense that more families are in need helped drive the change. Catholic Charities also sees a growing need and has embarked on renovations at its Samaritan House that will result in four more rooms on its family floor, bringing the total to 25. Samaritan House has a 120-day program for families aimed at getting them into permanent housing.

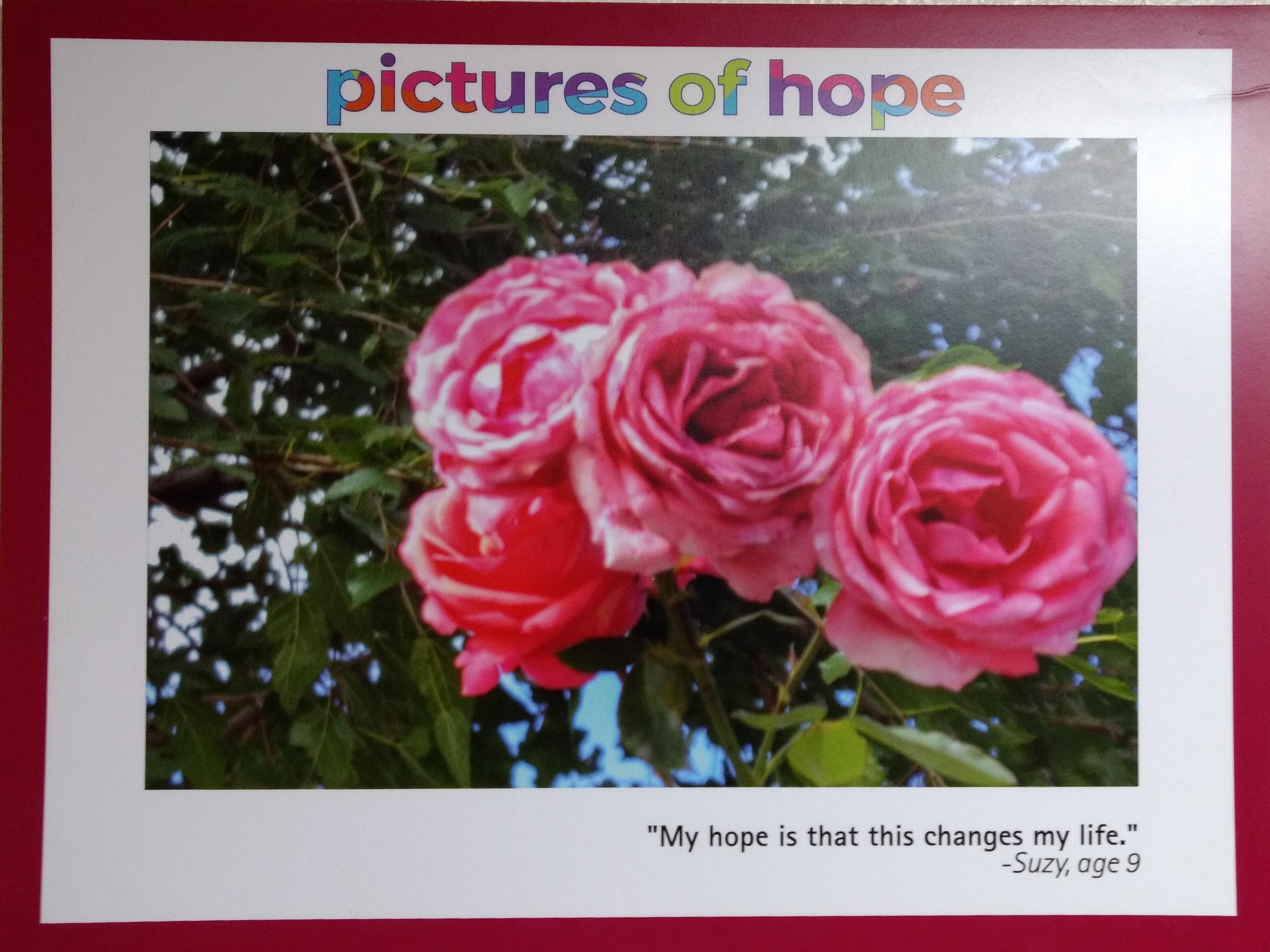

Lambuth has space for 20 families. Each gets a private room with a bathroom, off hallways decorated with the artwork of resident children. Three meals are provided every day. A preschool is on site, its walls splashed with a mural painted by volunteers as part of the renovation, which also included new flooring and furniture elsewhere in the building.

The Salvation Army gets referrals from Volunteers of America and other agencies. All that's asked is that households have at least one minor and adults have no violent criminal record. Once families move in, they are not required to accept the training and other support on offer, which include classes on parenting and financial literacy.

Newton, Lambuth's program manager, said some families do need structure. But she doesn't want requirements to slow families that are on the right track on their own.

Lambuth residents are expected to start looking for permanent housing as soon as possible. Salvation Army navigators offer support hunting for homes and negotiating with landlords.

Baluyot said finding affordable housing is a challenge in Denver's overheated market.

"I've got magic makers, as far as my staff goes," she said.

Navigators look outside Denver and adding that families have been flexible. Some families have found homes outside metro Denver, as far as Grand Junction and out of state in a few cases.

"There is not one single thing that brings folks into homelessness," Newton said. "There is no easy answer to bringing people back into housing."

Convinced that speed is key, Baluyot would like to see the 90-day stay reduced to 60.

Claire Limbric, a single mother of three, moved from Lambuth into subsidized housing after 30 days.

It would have been sooner, but she needed an extra day or two to work out the logistics of a new route to school for her children. Lambuth had helped her get her children back in school after a hiatus because of their homelessness.

"It's just remarkable that people here care so much about people they don't know," Limbric said of the Lambuth staff.

Limbric had left her job as a waitress in Virginia to move to Denver to be with a boyfriend who turned out to be abusive -- and to have no place for her and her children to live. She was referred to the Salvation Army by Volunteers of America and moved in to Lambuth soon after its renovation and redirection.

Now Limbric is looking for a job.

"I like waitressing," she said. "I'm a people person."