Playwright Bobby LeFebre overheard her in one of the new bars in his old neighborhood.

A woman was telling a friend about a stranger in a passing car shouting an insult at her for carrying a yoga mat down the street. She told her friend, LeFebre remembers, that "these people have no idea how awesome it is to live close to the place that you meditate."

LeFebre, who was baptized at North Denver's Our Lady of Guadalupe, heard absurdity in the comment. It may not have occurred to his unknowing muse that people who had called the neighborhood home for generations before she called it Highland treasured being able to walk to prayers. LeFebre included the line -- changing "meditate" to "pray" -- in his new play because he also heard the woman's sincerity. He holds out hope that the gentrifiers and the gentrified can find enough empathy to have a conversation.

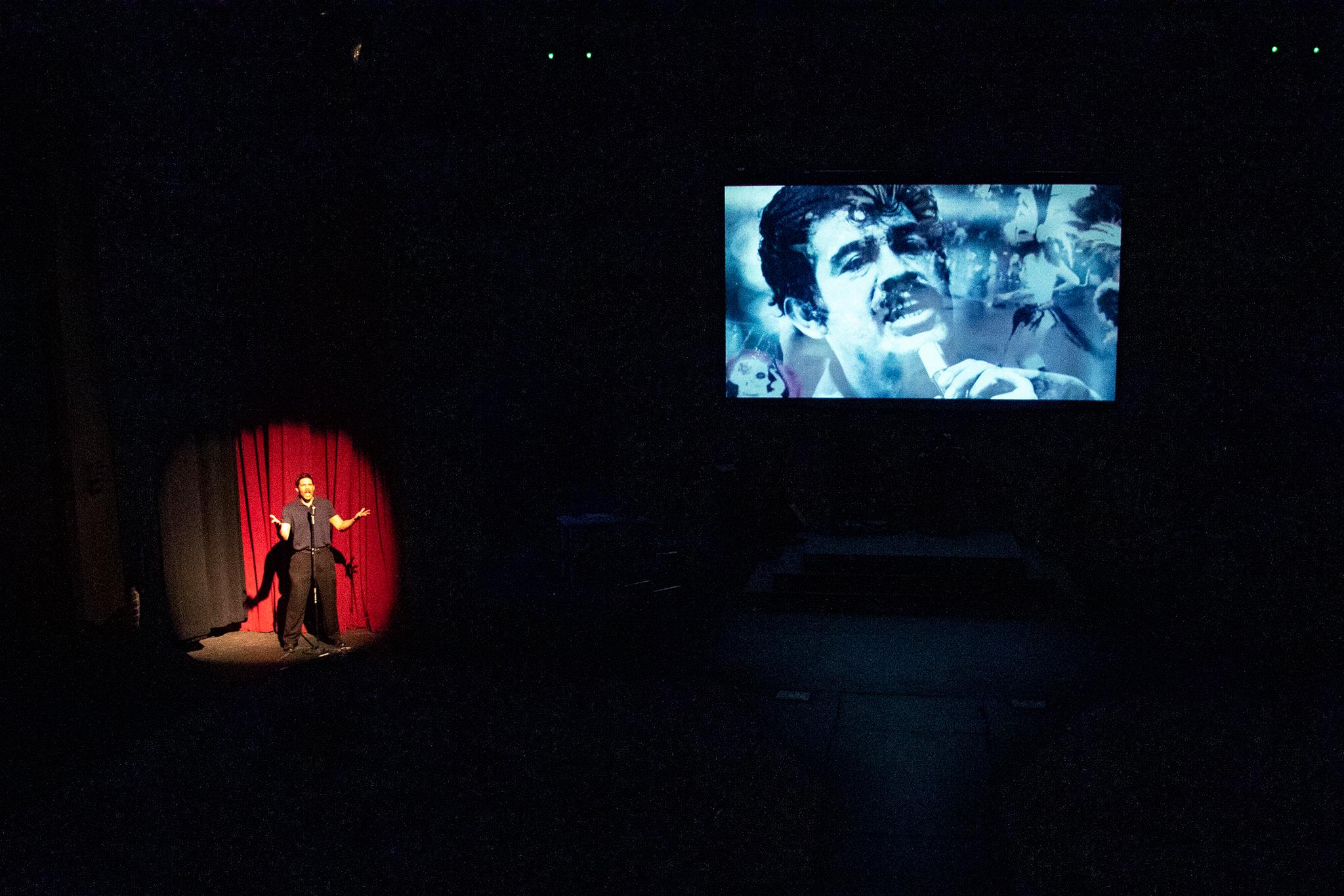

LeFebre's "Northside" opens Thursday at Su Teatro in the Art District on Santa Fe. Tickets are selling so fast that extra shows are being considered. That's a sign, LeFebre said, of a burning desire in Denver to talk about development and displacement. It's not just the primarily Hispanic north and west Denver neighborhoods that have faced a sudden influx of moneyed, white newcomers. Last spring LeFebre saw "Honorable Disorder," in which another local playwright, Jeff Campbell, tackled the gentrification of historically African-American Five Points. LeFebre responded with poetry to the infamous "happily gentrifying" sign at a Five Points ink! Coffee.

LeFebre makes room for everyone on stage. He knows that in real life it will take more than introspection and goodwill. If Denverites can get past the shouting, perhaps they can start to work together toward solutions that will allow communities that have long been marginalized a chance to benefit from their city's boom.

In the meantime, LeFebre offers "Northside" as a tender, sometimes comic, sometimes magical "celebration of what we had, a mourning of things lost and some questioning of whether we even fit in any more."

LeFebre's great grandparents, grandparents and parents all owned Northside homes. He and his wife ended up in a bidding war when they tried to buy a few years ago. They were able to persuade the seller they were the right buyers.

In "Northside," Luna and Teo struggle to buy in Sunnyside, where they grew up. They find real estate rivals in a yoga- and craft beer-loving Megan and Sean, a white couple from the suburbs whose main claim to a connection to the neighborhood is knowing the owners of a new kombucha brewery.

"I love Mexican food," declares Sean, who sometimes channels Archie Bunker.

"What about Mexicans?" Luna retorts.

The house is not just the focus of their bidding war. It is the home where widowed Mrs. Lujan and her beloved Juan listened to the laughter of their grandchildren and great grandchildren.

"I just wanted to fill this house with people who would appreciate what we built," Mrs. Lujan said. "Not destroy it."

Su Teatro itself gives reason for hope that traditions can be preserved and allow the future to flourish. Under Artistic Director Tony Garcia, the cultural and performing arts center has kept alive the stories of Denver's Hispanic residents. One recent production chronicled events of the spring of 1969, when students at nearby West High School walked out to protest racism and were met by police wielding tear gas and batons.

"We're still here. We're still representing the neighborhoods. We're not going down easy," said LeFebre, now 37, who got his start as an actor when he was a teenager and later as a director at Su Teatro.

"They have my headshot upstairs," he said in a pre-rehearsal interview. "It's always been my creative home."

LeFebre thinks of himself primarily as a poet. He has a national reputation as a slam artist. His first paycheck for his writing came from a Su Teatro poetry festival.

Hugo Carbajal also started his career at Su Teatro. Carbajal, who came from his current base in Los Angeles to direct "Northside," didn't think the text he first saw had enough poetry.

"There needs to be more of you in the script," he told his old friend LeFebre.

LeFebre revised. Carbajal highlighted some of the poetry by staging stylized passages in which the actors gesture like dancers as they recite, allowing the audience to pause and reflect.

"Living paycheck to paycheck is never fashionable. There was beauty in the struggle, though," the chorus intones at one point.

Carbajal and LeFebre weave together surreal moments with nonfiction from LeFebre's own experience, current and historic events and the playwright's research/eavesdropping in trendy bars.

LeFebre has been able to tackle big themes from many platforms. He wrote his first poem about gentrification more than a decade ago. He later started "We Are North Denver," a digital and grassroots campaign of storytelling and activism in response to racist leaflets scattered in his neighborhood a few years ago. Five years ago an early draft of "Northside" got a staged reading at Su Teatro. LeFebre then created the "Welcome to the Northside" Web comedy series. In one of the eight episodes, a version of the yoga lady claims to have "discovered" a neighborhood panaderia and to be more Latino than the local character LeFebre plays because she studied Spanish in Ecuador.

Food is cultural territory for LeFebre. His "Northside" characters pick up burritos from Chubby's and conchas from that panaderia, both of which -- like the playwright -- are so far successfully surfing fast-changing Denver.