Updates with certified results posted.

Lakewood voters approved a 1 percent cap on housing construction in a special election that ended Tuesday night with the neighbors behind the "Strategic Growth Initiative" celebrating over a potluck at the home of the woman who led them.

Proponents launched a petition drive and overcame a court challenge to get to Tuesday's one-issue special election. Led by schoolteacher Cathy Kentner, they argued their city west of Denver was growing too quickly and their roads, parks, sewers and other infrastructure weren't keeping up. They also raised concerns about the power of developers and loss of identity, echoing arguments heard along a changing Front Range where transportation infrastructure is under pressure, housing prices are rising and gentrification is leading to displacement.

Kentner, who was heavily outspent, attributed the victory to "all of our volunteers. Those who signed our petition two years ago and everyone who volunteered since."

Speaking at her home surrounded by friends and supporters, she added she hoped the result would spur others who felt ignored by their elected officials to take action on the issues that mattered to them, not necessarily growth. She said her own initiative "is a reasonable compromise. This is not anti-growth."

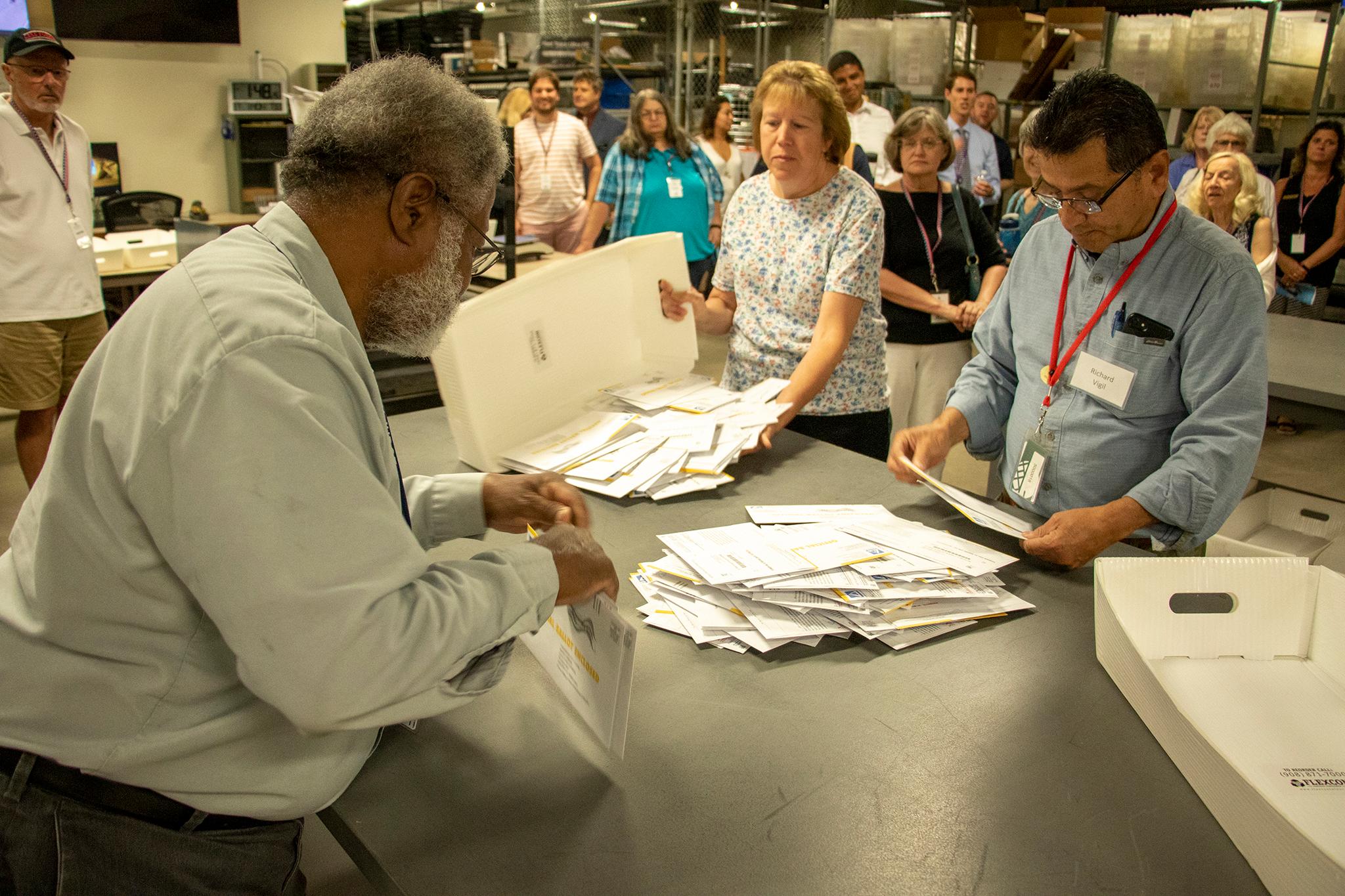

Shortly after polls closed at 7 p.m., the first results showed the "yes" vote with about 53 percent to 47 percent for "no." Jefferson County Clerk and Recorder George Stern said that reflected a substantial portion of the more than 30,000 votes cast -- more than a third of registered voters took part in the election in which ballots were mailed and voters could return them by mail or drop them off at designated sites.

While the results were incomplete and would not be official for several days, they were clear enough for Mayor Adam Paul, who had opposed the measure, to concede defeat.

"It's time for us to come together as a community and try to figure out how this is going to work," he told Denverite.

According to certified results posted by election officials July 12, 52.61 percent of voters approved the measure.

Opponents said Ballot Question 200 was wrongheaded in trying to squelch growth -- the alternatives, they argue, are stagnation or losing opportunity -- instead of proposing solutions to its unwelcome consequences.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated Lakewood's population at about 150,000 in 2018, up about 10 percent from 2010. Neighboring Denver over the same period grew about 20 percent, to about 700,000. In Denver, concern about growth shook up the May election and June runoff, with three incumbents ousted from the 13-member City Council. Mayor Michael Hancock, for good or ill closely linked to Denver's dizzying growth, won re-election only after a runoff.

In addition to calling for limiting new home construction to 1 percent per year, the Lakewood initiative requires the city council to approve projects with 40 units or more. It outlines a process for determining at the start of each year how many building permits for housing can be issued -- 1 percent of the existing stock, with exceptions for, for example, proposals to build in areas determined to be "blighted." According to the ballot language, 200 aimed to safeguard Lakewood's "unique environment and exceptional quality of life;" encourage the preservation of large open space areas and the development of "distressed areas;" ensure that infrastructure and services are not stretched thin; protect the environment and avoid "increases in crime and urban decay associated with unmanaged growth."

"Most people have moved to Lakewood to experience a suburban environment," Kentner said during a pre-election forum on the proposal organized by Jefferson County's League of Women Voters.

Bill Furman, a longtime Lakewood resident who spoke for the opposition during the forum, countered that Lakewood "is a city that has gone from a bedroom community to a community that supports numerous big businesses."

Kentner and other organizers had collected thousands of signatures to get the proposal on a ballot or adopted by the city council. Their effort was delayed by a suit filed by Steve Dorman, who has been active in Jefferson County politics and expressed concern about the proposal's possible impact on property rights. Dorman's legal effort failed and City Council in April voted to hold the special election. Council also adopted new regulations that would prevent a court challenge like Dorman's from delaying a vote of the people should a similar case arise in the future.

Lakewood Mayor Paul had been an early opponent of the measure, expressing concern it would limit the city's ability to build affordable housing and only make growth harder to manage. He has said concerns about the impact of growth can and are being addressed in his city, pointing to recent moves such as requiring developers to include more open space around apartment buildings. Kentner said those measures were too little, too late.

Paul also noted that last year Lakewood voters approved lifting limits set by the Taxpayer's Bill of Rights, or TABOR, to allow the city to spend $12.5 million in tax revenue on such things as improvements to parks, sidewalks and traffic signals.

Paul had predicted parts of the initiative could be challenged in court if it became law. The requirement that city council approve projects with 40 units or more, for example, could clash with zoning rules that allow such structures in some parts of town.

"There's a lot of projects in the pipeline. I don't know how those will be affected," he added Tuesday night.

Six months after the new measure is implemented, City Council will be able to consider whether amendments are necessary.

Charley Able, a Lakewood city councilman, supported the initiative on growth.

"Slower growth will give us a chance to catch up on the infrastructure that we need to serve all of these people," he said, though he acknowledged coming up with the money would be a challenge.

Politicians who joined Paul in opposing the initiative included former U.S. Rep. Bob Beauprez, a Republican, and Andy Kerr, a former state senator and a Democrat. Concern about the initiative came from across the region, in part out of a fear that success in Lakewood could lead to similar efforts elsewhere, and in part because of predictions that constraints on growth in one corner of metro Denver would likely push development elsewhere.

Kelly J. Brough, president and CEO of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, said in a statement ahead of the vote: "We are urging Lakewood voters to vote no on this ballot question. We know it's not the answer for Lakewood or our region."

The Denver Metro Association of Realtors, in its latest monthly report released Wednesday, said the average sale price of a single-family home in the area last month was $547,461, down slightly from May -- but May was a record month, with an average price of sold for $555,482. The June average this year was up 1.26 percent over last year in the area that include the Lakewood's county of Jefferson as well as Denver.

Business interests lined up against 200 included the Colorado Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, the Jefferson County Economic Development Corporation and the South Lakewood Business Alliance.

Last year Daniel Hayes proposed a 1 percent cap for at least two years for not just Lakewood but all of Jefferson County as well as Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield Boulder, Denver, Douglas, El Paso, Larimer and Weld. Hayes helped Golden put similar limits in place in the '90s, and Boulder also has longstanding curbs on growth. Hayes claimed taking such a step across a wider region would mean higher wages, keep housing prices stable by discouraging people from moving to Colorado, and discourage unauthorized immigrants who work in the construction industry. Hayes's proposal never made it to the ballot because he waited too long to start gathering petition signatures.

Carrie Makarewicz, an assistant professor in the University of Colorado Denver's College of Architecture and Planning, has studied anti-growth measures and what she sees as artificial caps on development. The impact in Boulder, she said, has been a housing shortage that has increased traffic because people who cannot afford to live in the city are commuting to jobs there.

"Growth is inevitable. People are having babies. People are living longer. And we cannot say people can't move to Colorado," Prof. Makarewicz said. "It's just shuffling the deck chairs on the Titanic to say, 'We don't want growth in our community."

Makarewicz's suggestions for addressing problems associated with growth include encouraging density to conserve open space and cut down on commuting time. She also recommended managing growth across regions so that development is directed to places that can best absorb it. Spending on infrastructure has to keep up as populations swell, and limiting growth could mean limiting the tax revenues cities need to improve their infrastructure, she added.

Spending in Colorado is constrained by TABOR, legislation passed in 1992 that prohibits increasing taxes without a vote of the people and limits how much revenue government can spend. The 1982 Gallagher Amendment to the state constitution, meanwhile, has hit property tax revenues. TABOR and Gallagher might be better targets than growth for people looking for ways to cope with change, Makarewicz said.

In an op-ed against 200 in Westword, urban policy consultant Jonathan Cappelli linked Golden's growth limitations to "the fact that the median list price for homes is a staggering $629,000, and the median rent rate is listed at $2,468 per month."

"If you want to address affordability, you need to shape housing development rather than restrict it. Appropriate policies for this approach include passing inclusionary housing ordinances that require developers to make a certain percentage of new units affordable, creating affordable housing development funds, and passing other developer regulations or incentives," added Cappelli, who is also executive director of the Neighborhood Development Collaborative of nonprofit housing organizations in metro Denver.

Other affordable housing advocates also questioned 200, whose proposals could mean extra steps along an already difficult road to finding sites and raising funds to build homes that can be offered at below-market rates.

"Habitat for Humanity of Metro Denver has been building and preserving affordable home ownership for 40 years, and we believe it's critical that hardworking and essential members of our workforce be able to afford to live near the communities where they work," Maria Sepulveda, the organization's vice president of government and community partnerships, said in an email late Tuesday. "While we support responsible growth, we were opposed to Ballot Initiative 200 because we're concerned it could have unintended consequences that will suppress affordable homeownership. However, we respect the opinions and voting results of Lakewood's residents, and look forward to continuing to collaborate with Lakewood's residents, elected officials, and other community organizations to increase the supply of affordable housing in Lakewood."

Anita Springsteen, who joined Kentner in pushing for the initiative on growth and now is running for City Council, said the new rules would allow for affordable housing that she sees as having been concentrated in certain areas to be placed all over Lakewood.

"If you look at the people involved (in passing the initiative), we are the people who need affordable housing. We are those teachers and ethnic minorities and single moms," she said.