A new policy aimed at quelling disruptive protesters in Denver's courthouses has been used against peaceful activists at city hall.

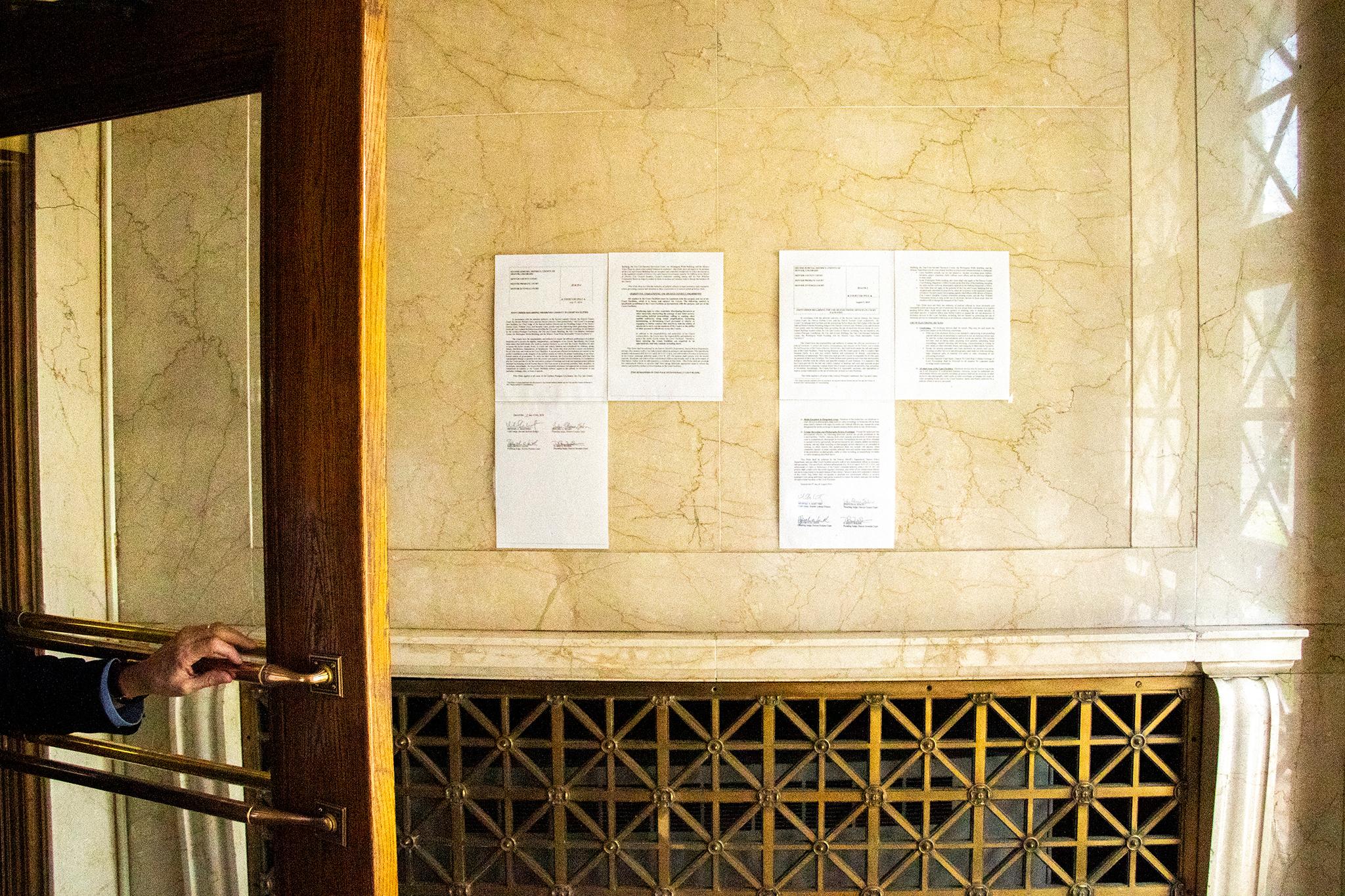

On Aug. 9 four Denver judges signed a judicial order that preempts people from using phones and other devices to record what happens in parts of the City and County Building -- Denver's city hall -- as well as courthouses and municipal office buildings.

Denver's government buildings belong to taxpayers, but the general public cannot freely record audio or video inside certain spaces without permission. Judges already had discretion to limit recording in courtrooms. The order gives police officers, deputies and private security contractors discretion to enforce the order at buildings that house the executive, legislative and judicial branches, but its main target is offices in the judicial branch, Second Judicial District Chief Judge Michael A. Martinez told Denverite. He wanted to prevent (sometimes loud, sometimes violent) spectacles from impeding court business.

"Over the course of the last few years it's been increasing in nature and occurrence, we're seeing an uptick in events that seem to be aimed at disrupting the conduct of essential court business," Martinez said. "And so it became necessary for us to at least set some guide posts for how to manage those type events to allow us to the greatest extent possible."

No one person fueled the new policy, according to Martinez. But notorious government agitator Eric Brandt has threatened to kill judges and regularly livestreams his interactions with public officials at Lindsay Flanagan Courthouse, which led to increased security for judges, according to a CBS4 report.

First Amendment lawyer and president of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition Steve Zansberg helped forge the new order over a year-long process. He said Brandt's actions partially prompted the new rules along with other agitators.

The order targeted the city's judicial branch. Yet a Denver sheriff's deputy stopped Denver Homeless Out Loud advocates from filming in the hallway outside of the Denver City Council chambers, part of the legislative branch, on Aug. 19.

Group leader Terese Howard said the deputy justified his actions with the new order. She posted a video of the incident to the group's Facebook page. The homeless advocates had been prepping to speak at a public hearing that evening.

"We had no amplification equipment. We were simply giving a presentation about homelessness and during our presentation, we were live-streaming it with our phones, and the deputy or whatever walked up to us after a short time," Howard said. "He threatened to arrest us ... and forced us to turn off the phones saying there's this law that bans us from filming in the hallway.

"We had been planning on giving a presentation in the hallway because the whole event is based on the fact that it is our government and it is our government building, and as such, we the people should use our space and use our voices there."

The sheriff's department did not document the incident and does not have a system to chronicle these types of interactions internally, as far as department spokeswoman Daria Serna knows.

Last week the Denver City Attorney's Office ordered law enforcement to let people record in that space while the City Council is in session. A designated space was roped off. Spokesperson Ryan Luby said he could not say whether the Aug. 19 incident fueled the policy change, but said members of the public had expressed concern.

Judge Martinez had not seen the video or heard about the incident, he said. His order does not apply to the areas where the mayor's office and City Council do their work. Nor does it preempt law enforcement from stopping recordings they deem disruptive.

First Amendment attorney and freedom-of-information advocate Zansberg wondered if the order shrinks freedoms because of a few bad apples.

"Part of what I was doing in meeting with this group (of judges) was to make sure that you're not treating non-disruptive members of the press and public too harshly because of the actions of people ... who are involved in civil disobedience," Zansberg said. "The thing about civil disobedience is that it means you're willing to violate the law to make a point. You can't do that without consequences."

He helped the judges draft the order, which carves out special privileges for members of the press -- a piece he believes might have been omitted without his advocacy.

Zansberg said, "As much as I advocate for and believe that there ought to be a right to videotape and record or photograph governmental proceedings open to the pubic so much as it's not disruptive, there ought to be a way for courts to carry out their business."

Judge Martinez, Denver County Judge Theresa A. Spahn, Denver Probate Court Judge Elizabeth D. Leith and Denver Juvenile Court Judge D. Brett Woods all signed the order.