Rebellion, betrayal and murder underscore the new play by Brenton Weyi, a longtime Denverite and one of four playwrights in the Denver Center for the Performing Arts' new fellowship for rising talents.

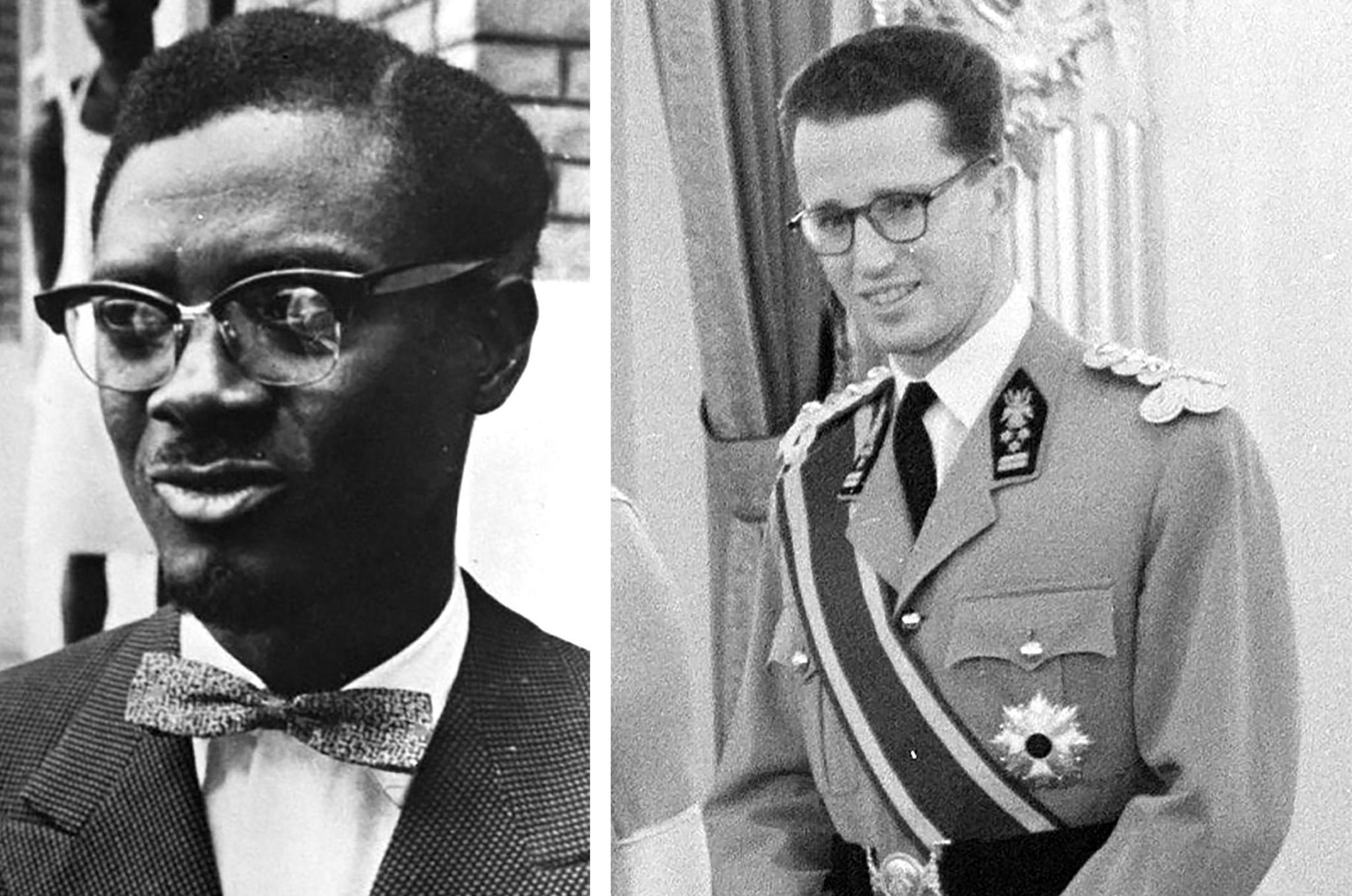

At a glance, "My Country, My Country" reads like Shakespeare, but it's no fiction. It's the true story of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Republic of the Congo and a revolutionary idealist who helped steer the country out of Belgian rule in the 1950s. Weyi spins a tale of Lumumba's rise and fall through his musical, which features freestyle raps and group harmonies.

Weyi and his collaborators will show off an excerpt of the piece Thursday evening in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science's Botswana Africa Hall. It's not quite Congo, but Weyi said it's close enough.

"When I put on events, I always think about how can I make an enchanting experience for my audience," he said, "to capture people's imaginations."

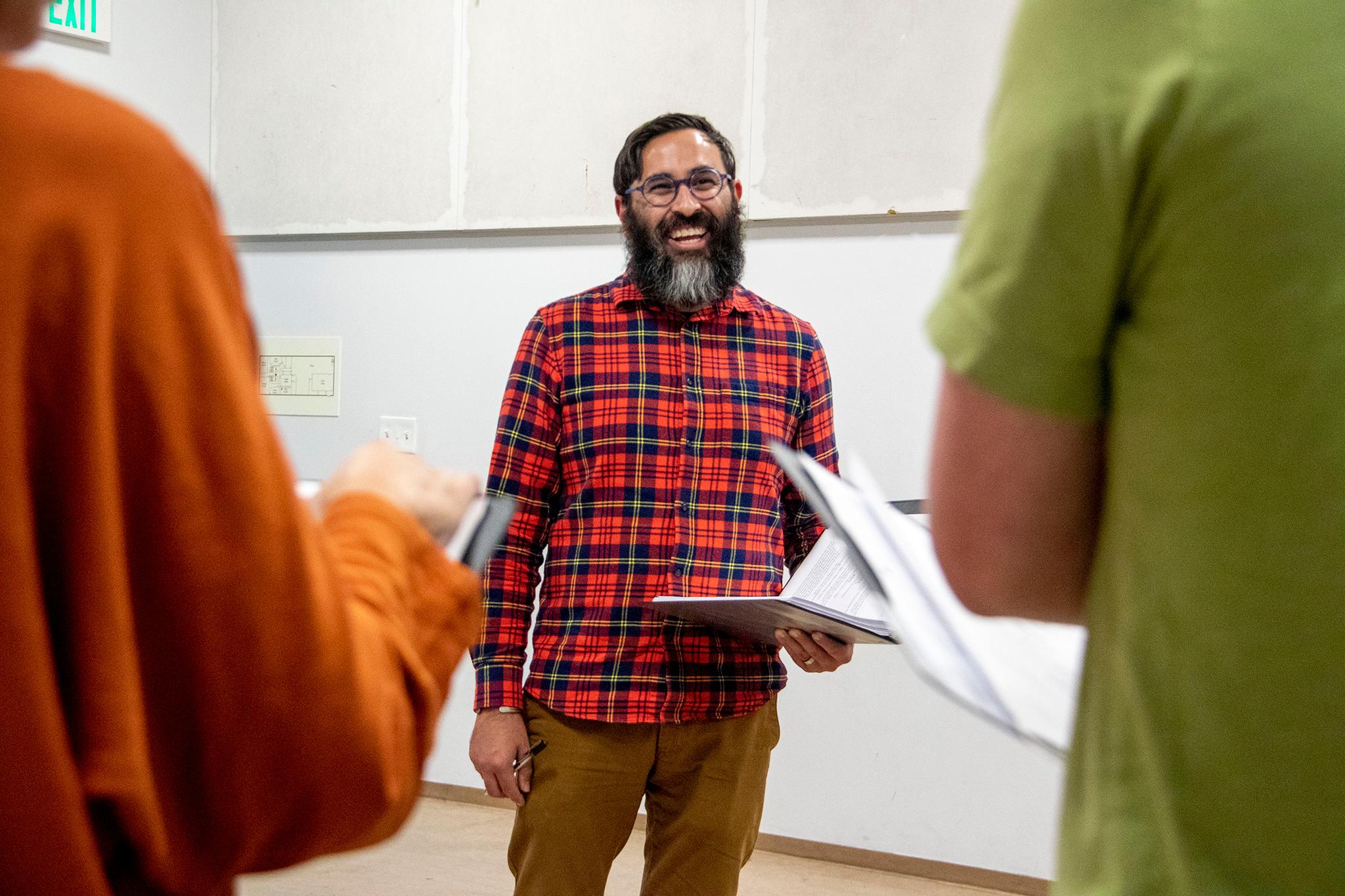

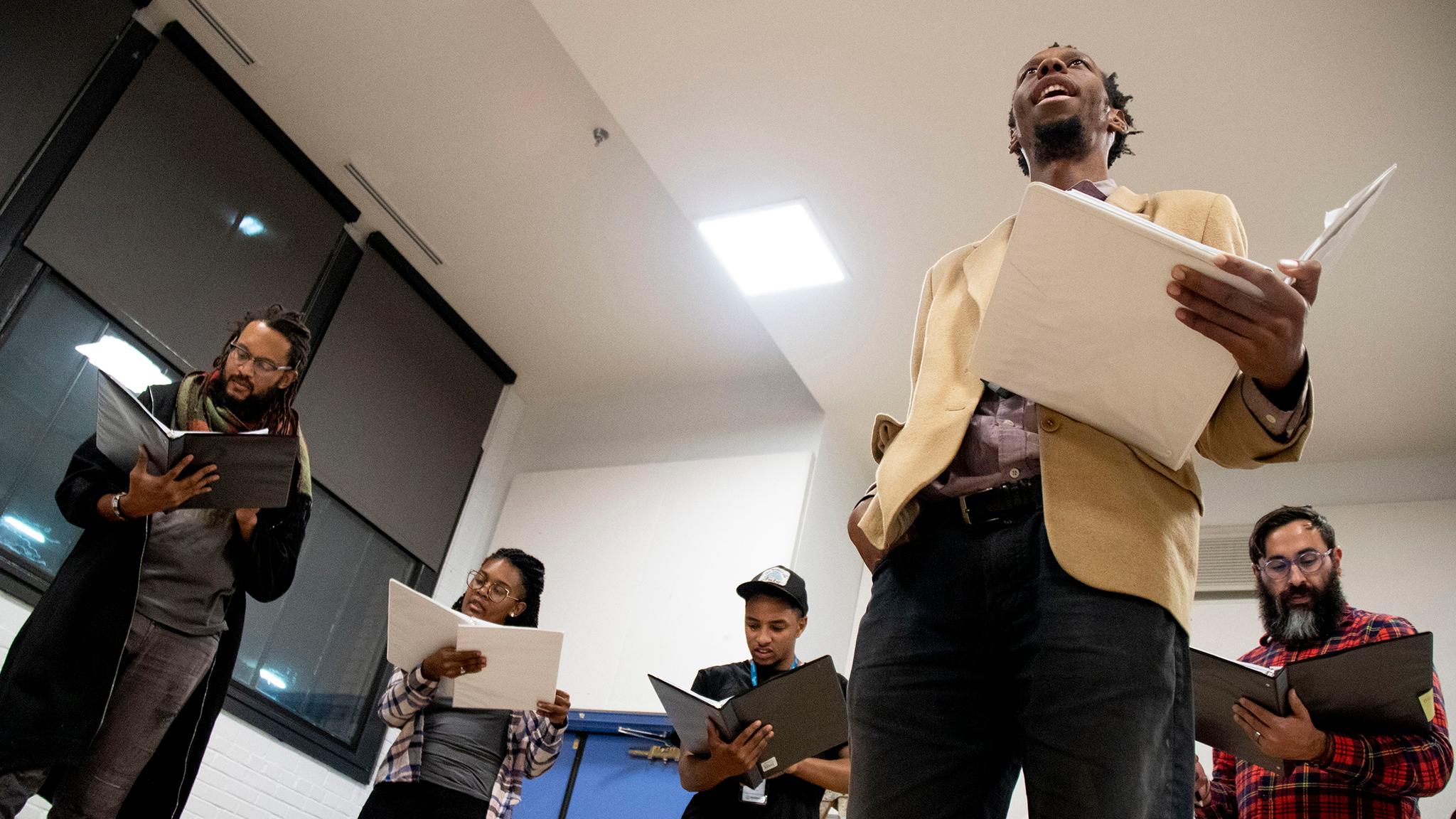

Manuel Aragon, who worked with Bobby LeFebre on his "Welcome to the Northside" web series, is directing the show. Stephen Brackett, a member of the Flobots and founder of Youth on Record, is among the cast.

This play has been in the works for years. The new DCPA fellowship gave Weyi the tools to see it through.

Congo is a place that's very close to Weyi's heart. His great-great-great-grandfather was Simon Kimbangu, who brought "Africanized Christianity" there and mounted, in Weyi's words, "one of the most effective resistances" to Belgian colonialism. The religious movement still has influence in the country, which is called Democratic Republic of the Congo today. Weyi's mother's uncle now leads the church. Weyi's father ran an unsuccessful campaign to be the country's president in 2016.

Weyi said the story of Patrice Lumumba and the conflict with Belgian King Baudouin that resulted in his execution has long gripped his imagination. Legend has it that Kimbangu sat down with Lumumba when he was young and prophesied that, one day, he would lead the country. The story goes that Kimbangu shared the same prophecy with Lumumba's best friend, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who oversaw Lumumba's killing and became Congo's leader soon after.

"It was the fable-like story that was the seed of the idea," Weyi said. "That was Shakespearean shit."

That seed germinated seven years ago, and Weyi began working on the script in earnest in 2015. But it wasn't until last June that he really had the resources to turn his vision into a reality.

Weyi, Jennifer Faletto, Jeffrey Neuman and Colette Mazunik were chosen to be the first fellows in DCPA's Playwrights Group, a fellowship meant to foster the work of local creatives writing for the stage. Each of the fellows are given a stipend, practice studios and mentoring as they develop their plays. In the spring, at the end of the fellowship term, each will present their full visions to the center's brass. DCPA will have 60 days to decide if they will commission any of the plays when the program is complete.

Lynde Rosario, DCPA's literary manager, said this fellowship picks up where the center left off with a similar support program dating back to the 1990s. Members of Denver's theater scene have been clamoring for something like it since the old program closed.

Last year, DCPA Off-Center curator Charlie Miller put out a survey asking local playwrights what kinds of professional needs they wanted to see filled. Rosario said they got an "outpouring of responses," and the requests were simple: "time, space, and money."

And as DCPA is helping these artists finish their projects, Rosario said the program is also beneficial to the Center.

"They have greater access to us and our resources, and we have greater access to them and their art," she wrote in an email. "The upside is that DCPA has greater access to local talent."

Though Weyi had access to plenty of resources and big stages when he attended Whitman College, he said it's been a while since he could play with a vision as large as "My Country, My Country."

"I had forgotten what that feeling was like in my adulthood," he said, adding that acceptance to the fellowship program was "a weird kind of homecoming or remembrance."

He needed those tools to breathe life into his story.

He said he had a hard time pitching this "multi-genre musical" focusing on "independence and decolonization in Congo" to people with no prior knowledge of the story. There's a lot baked into his vision, and Weyi said it wasn't until people started seeing bits and pieces performed that they really understood where he was taking it.

In a DCPA practice studio last week, Weyi, his cast and his crew put those resources to work. Though he's been tinkering on the script for years, they still had to do in preparation for Thursday's performance.

Will the line be: "I'm going to write for the biggest paper in Belgium" or "My writing is going to be published in the biggest paper in Belgium?"

They hashed it out. Words on a page, Weyi said, always need workshopping to fit the form of each actor's mouth.

"Is it worth doing this one more time?" asked musical director David Nehls.

"Yes!" the group exclaimed.

So they ran it, again and again, until it was perfect.

"My Country, My Country" is an attempt to inject an authentic African story into mainstream American culture.

In the last few years, as feature films like "Black Panther" and "Crazy Rich Asians" have become box-office successes, Hollywood power brokers have begun to re-evaluate a long-standing belief that movies centered around non-white leading characters couldn't become financial successes. Weyi said that conversation hasn't been happening at the same scale in the theater world, and he's hoping he can help change the landscape.

He was chatting with a friend a few weeks ago, trying to think of ways Africa was represented in theater.

"The only things I could think of were 'Book of Mormon' and 'Lion King,'" he said.

Even "Hamilton," which he said was lauded as a "triumph in representation," is still just "about a bunch of old white guys."

Weyi is attempting to tread a fine line with a piece he thinks could become a commercial success and still hold on to its authenticity.

"I don't want people to think this is some kind of Black Panther or Kunta Kente piece," he said, "fetishizing the characters into a trope that people want to see."

He decided not to ask his actors to speak with stereotypical African accents, and he said he believes the trappings of musical theater and the Shakespearian dramatics of Lumumba's life will help a general audience accept the story without diluting it with gimmicks. He thinks people are already coming around to the idea.

Manuel Aragon, the director, told Weyi something that stuck when they worked together on an earlier version of the script.

"As a writer of color," Weyi remembered Aragon telling him, "it is your job to destroy as many tropes with your work that you can."

"My Country, My Country" is still in development, and the script may well be challenged if it's ever sold outside of the DCPA. But Weyi said he'll never allow the authenticity embedded in his story to be compromised.

Correction: This story incorrectly stated that the fellowship playwrights would perform plays at DCPA's annual New Play Summit. That line has been removed.