A new, separated bike lane is coming to South Marion Parkway -- the street where 37-year-old Alexis Bounds was killed while riding her bike in July.

Denver Public Works is hailing the new lane as a critical safety measure in a widely used bike corridor that connects some of the city's largest bike path networks.

Bounds's death was Denver's second cyclist killing in a month and it sparked protest rides around the city. Cycling groups also erected two "ghost bike" memorials following the crashes. Before the meeting Thursday, Bounds's white spray-painted bike could be seen chained to its tree on Marion. Someone had tied balloons to it for Bound's recent birthday. The cards laid between the bike's tires read "Mom" and "Fantastic Daughter."

The new lane is part of the 2017 Elevate Denver Bond, which will fun $937 million in city infrastructure improvements. But while that bond measure passed with over 70 percent of the vote, not everyone in the Washington West Park neighborhood approves of the new bike lane.

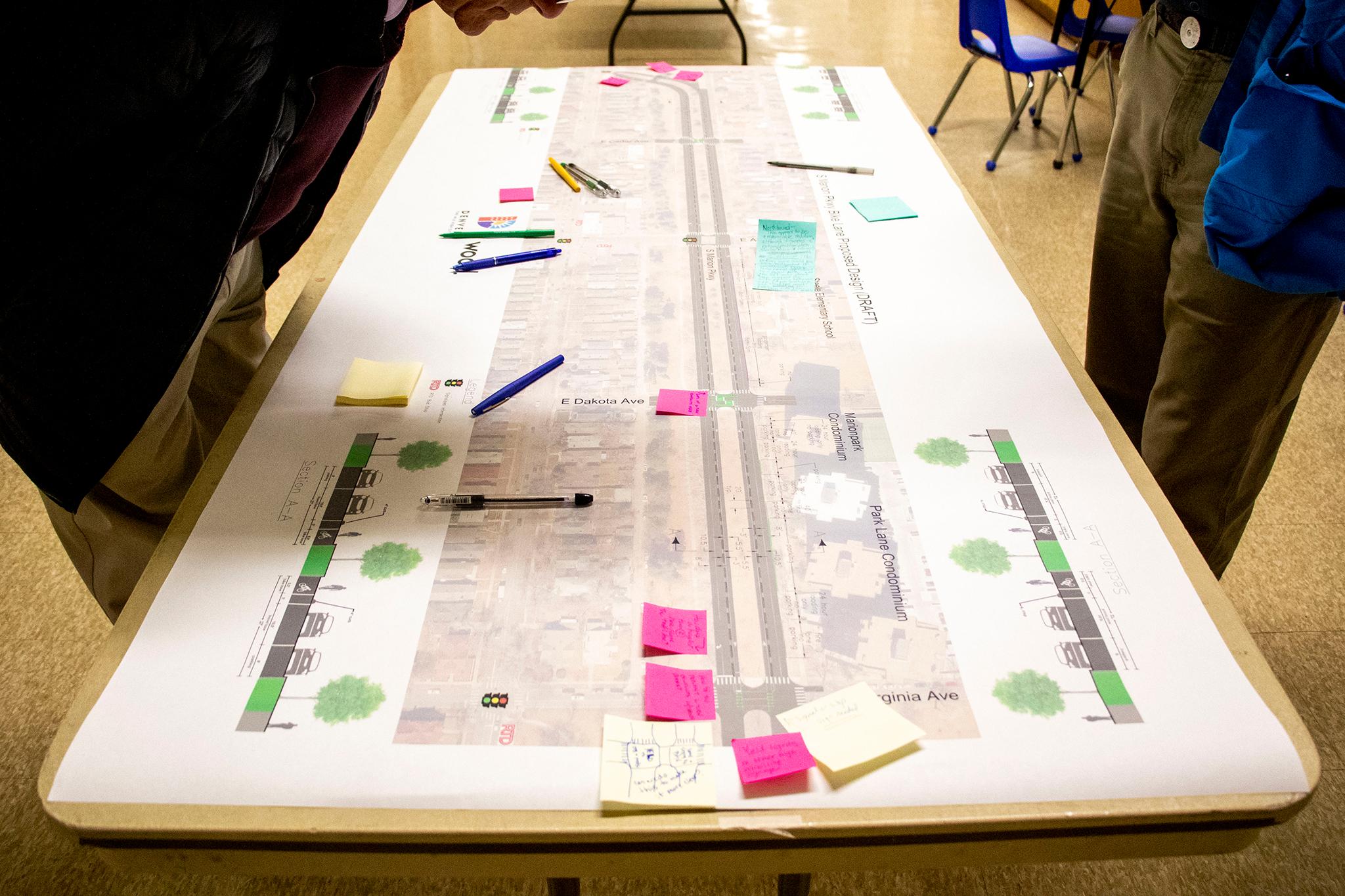

The small auditorium at Steele Elementary school was packed Thursday night for a meeting about the lane. Bike advocates had asked people to wear blue to show their support for the project, but it was easier to spot supporters by the bike helmets they carried after riding over for the event. Those against the project mostly wore scowls.

The new lane will run along the median of Marion Parkway and have a small barrier with pylons to separate it from the parked cars and loading zones. Lanes like this that are separated from traffic by a barrier are what the city is calling "comfort bike lanes."

There is an existing bike lane along the right side of the road, between traffic and a row for parking. The city calls this a high-stress lane because there is no physical separation between cyclists and moving cars. Parked cars can also pose a hazard to cyclists in the current bike lane as its close enough for drivers to accidentally hit a passing cyclist with their doors.

While the city and bike advocates say this lane will help improve safety on the street. Many in the audience said they felt that a change to the bike lane was unnecessary and that the pylons would damage the look of the road.

"We have no transit. Everyone drives cars," said DeDe Arnholz, a resident of the Park Lane Condominiums on Marion. "How does this address that bigger problem other than making this beautiful parkway ugly, ugly, ugly."

Marion is designated as a historic parkway, which comes with certain protections and design rules. These rules are what have prevented construction of a completely off-road bike lane in the area, something many residents have said they would support. It is only the area between the curbs, however, that lies completely within public works' jurisdiction. Officials from the public works department told residents at the meeting they have taken into consideration the historic look of the parkway, but still see a separated bike lane as a priority.

"I think the plan they are putting forward shows that they are listening," said Paul Kashmann, the city councilman for District 6, which includes Marion Parkway. "But safety has to be the preeminent concern."

There were also many at the meeting who supported the bike lane. Those with small kids were particularly enthusiastic about a separated lane. Amy Kenreich, a mother in West Washington Park with a 10-year-old and a 6-year-old only lets her kids ride on lanes with a barrier. She said that this lane would open up bike trips to the whole downtown Denver area to her and her kids in the summer.

"When my kids listen, they listen really well, but they only listen about eight out of every 10 times," she said. "I wouldn't risk taking them [downtown] now, I wouldn't risk their lives that way."

Correction: This story has been changed to reflect that it was bike advocates, not the city, that asked supporters to wear blue.