Denver's Office of the District Attorney is pitching a specialized court within the city's judicial system aimed at preventing gun violence among young Denverites. Some elected officials and advocates say the intervention will come too late in the game while others say it would only address a tiny piece of a larger puzzle.

A "gun court" would involve a judge, prosecutors, public defenders and probation officers tasked with treating first-time, juvenile gun possessors with empathy instead of a punishment. The goal is to prevent young people from committing another gun-related crime and spiraling through the criminal justice system.

"I think it's really important to understand how unique a specialty court is," said Priscilla Gartner with the public defender's office. "When you're dealing with a specialty court the prosecutors are not engaged in punitive work. They are engaged in therapeutic work."

Gartner spoke to Denver City Council members Wednesday during an unusually long meeting of the safety committee in which the DA's office, Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen and other officials from the Hancock administration presented the proposed approach to halting the rising gun violence around the city.

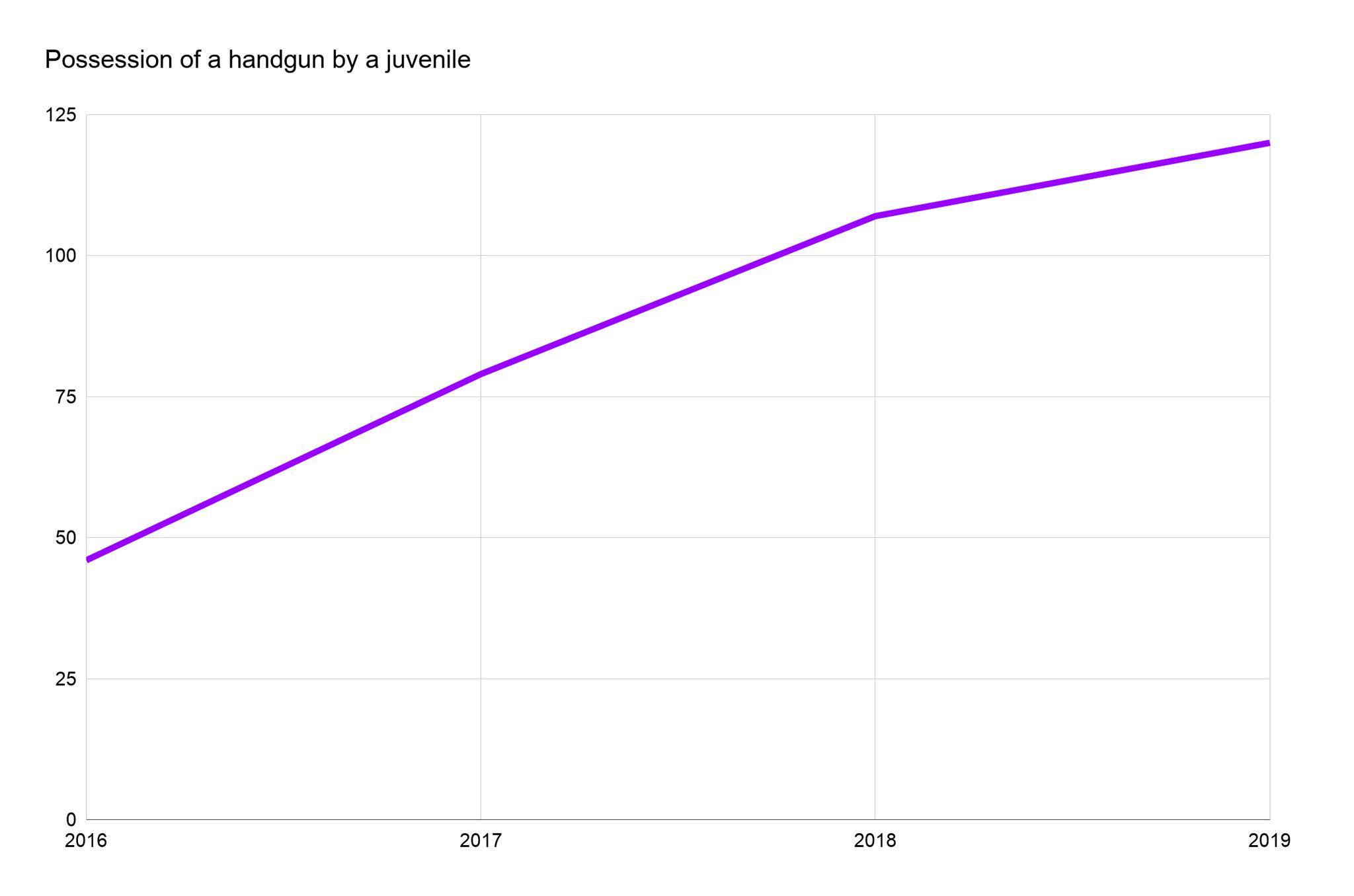

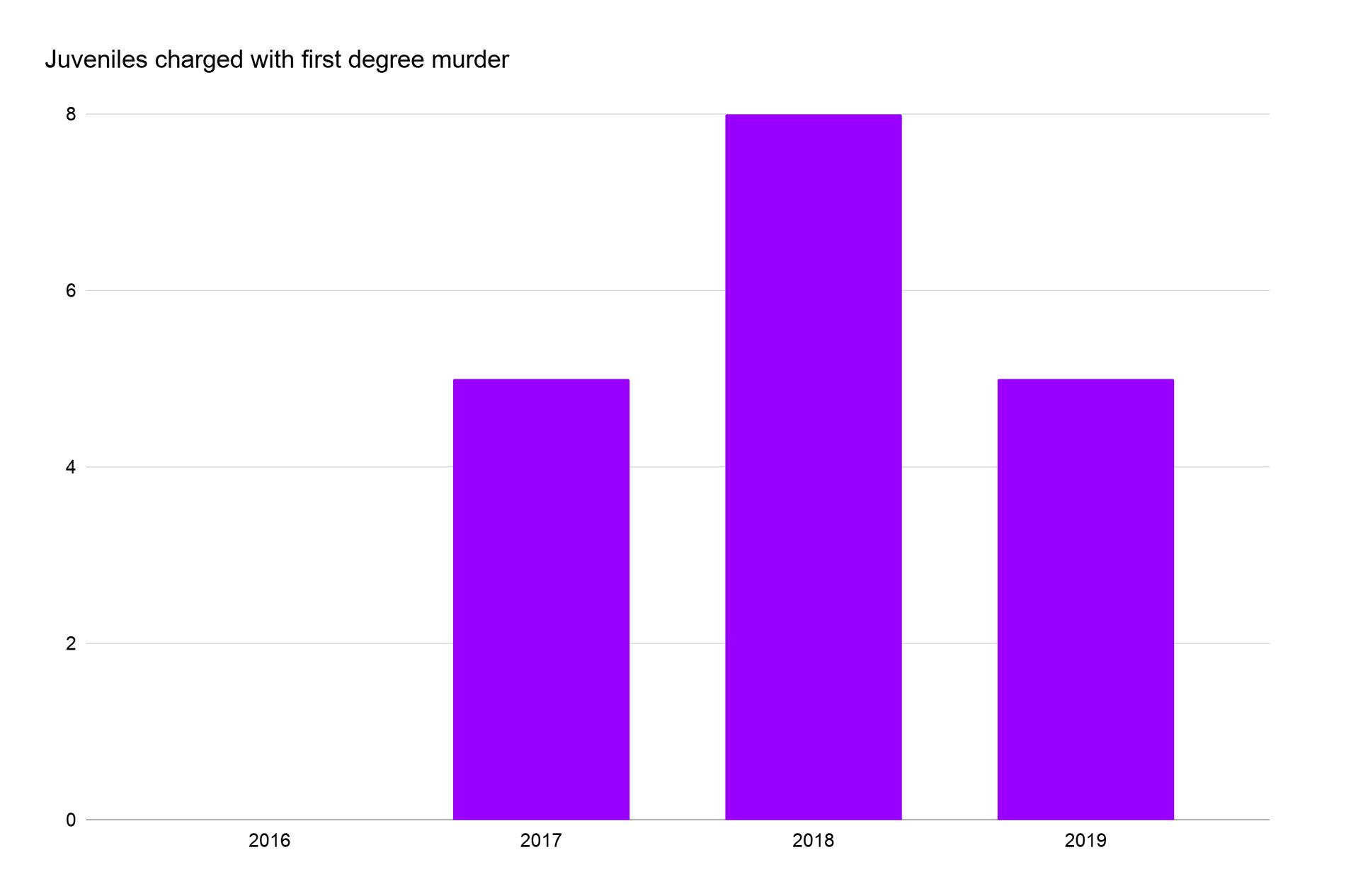

Five people under 18 were charged with murder last year and 120 were charged with possessing a handgun, according to court statistics. Those stats only account for people caught -- not the number of guns on the street. Prosecutors expect the homicide number to grow as more crimes are solved.

The gun court would mirror existing problem-solving courts, like ones for substance abuse, aimed at helping people get better and get out of the system. Some people call the approach "restorative justice." Based on a model out of Mobile, Alabama, Denver's program would fast-track cases that typically take weeks to get off the ground, intervening with offenders and their families early before putting kids through a six-month program that focuses on "their poor decision-making skills," a presentation from the DA's office states.

The probation period would serve 12 kids at a time and include education, drug screenings, community service, monitored attention to school work and counseling. Kids under 18 charged with possessing a handgun would have the option to join the program, Gartner said. People charged with more serious gun-related crimes might also join on a case-by-case basis, as well as second-time offenders.

Incentives include not going to juvenile hall and shorter probation than is typical. Also, gift cards. The program would still have punitive pieces, however: curfews, house arrest and detention would still be fair game for kids performing poorly by the program's standards.

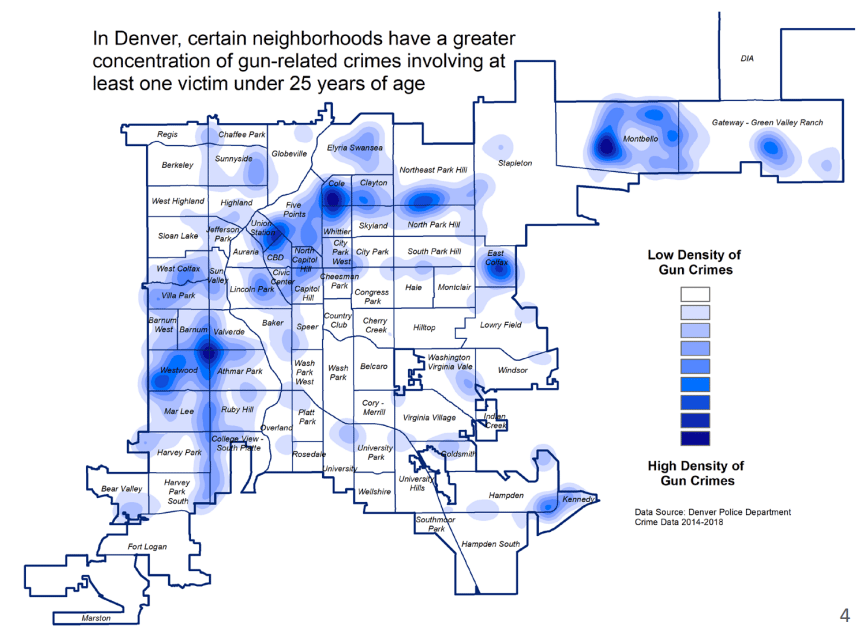

Councilwoman Stacie Gilmore represents Montbello and Green Valley Ranch, two of Denver's most violent pockets. She was not impressed.

"I feel like we're dancing around this issue and we're trying to address it through the courts, through the (DA's office) without pulling those layers back and addressing our families' health," Gilmore said, adding later, "I don't think that through serving 12 participants with the handgun intervention program is going to get us to where the folks in my neighborhood felt safe."

Gilmore said she wants to see more money and resources dedicated to her district and others to address underlying issues that lead to youth violence. She unleashed a long list of things that she says her far northeast Denver district needs: workforce development, financial literacy courses, "culturally relevant" mentoring, year-round educational programming, bilingual services and access to health care, among others.

Pazen referenced several DPD programs aimed at getting at the roots of crime, including mental health issues and gangs. But Gilmore and others are not seeing the results they want. Jason McBride, a former gang member youth advocate with Gang Rescue Support Project, told Denverite that a gun court would be "a waste of taxpayer money."

"We have to deal with the gang aspect first," McBride said. "We all used to identify with a school, a park, a neighborhood. I'm like, God, these kids are just cliquing up just playing Fortnite and then next thing you know, it spills out onto the street.

"So we have to get to the root cause of why these kids feel like they need to clique up and belong to something."

The handgun intervention program seemed like a good idea to others, but not a fix-all.

Councilwoman Robin Kniech called the intervention necessary but incomplete.

"I don't think we want the answer from probation and what your prevention is," she said. "We want the answer from outside the system."

There's no timeline for the program to launch and no guarantee it will. The DA's program will require funding from the mayor and/or Denver City Council.