Pssst! Pit Bulls are on the Denver ballot for Election 2020. Make sure you understand what you're voting on.

Denverite has received a ton of emails and comments about the saga of the city's pit bull ban. Our readers are very passionate about the issue, whether they think the ban should stand or be repealed - or whether they agree with Mayor Hancock's decision to veto the repeal measure passed by city council.

So we wondered: Has the ordinance always been such a flashpoint? The answer to that question is, generally: yes.

One way to tell is that the Denver Public Library's Western History Collection has an entire file of newspaper clippings on pit bulls, the only breed-specific folder in the collection. A dive into that archive shows that Denverites have been fighting over the ban since 1989, when it was first enacted.

"Pit-bull owners bare teeth at law" - Denver Post, Sept. 10, 1989.

City council had approved the rule on July 31, but now it had a legal fight to deal with.

The Colorado Humane Society and the American Dog Breeders Association filed suit against Denver, hoping to block the ban. In the months since it was enacted, Denver Post reporter Katherine Corcoran wrote, the city had "destroyed" about 100 pit bulls.

George Bentley was the lead attorney representing the plaintiffs. To make his point that the ban was ineffective, he trotted out three dogs to meet the press.

"Three well-mannered American pit bull terriers, one wearing a polka-dotted tie and sunglasses, were enlisted yesterday to help show the public that looks are only hair deep," the Post's story begins.

"Which one is a pit bull?" Bentley asked reporters. "Which one is a registered therapy dog? ... Which one is a trained attack dog? ... Which one is a family pet?"

Punk, the dog with the tie, turned out to be both a trained attack dog and a registered therapy dog.

The thing is, Bentley said, a "pit bull" refers to a dog trained to fight. Banning a specific breed meant punishing a lot of perfectly nice pets.

"No one can tell a dangerous dog by its looks," he said.

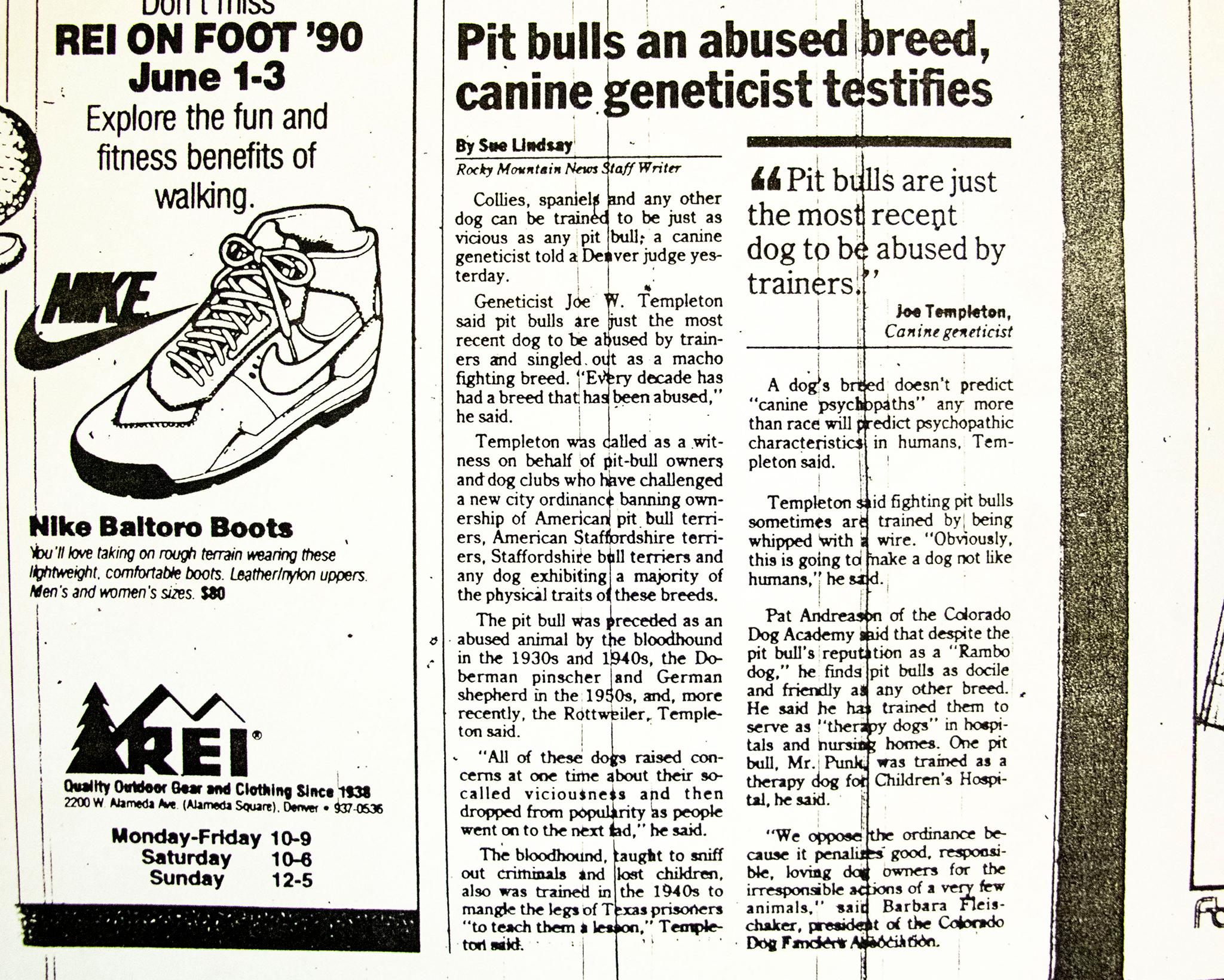

A Rocky Mountain News story quoted canine geneticist Joe Templeton: "A dog's breed doesn't predict 'canine psychopaths' any more than race will predict psychopathic characteristics in humans."

But Bentley had an uphill battle. City council's action came on the heels of two vicious attacks, and people were afraid.

Earlier that year, Rev. Wilbur Billingsley left his house at 20th Avenue and Emerson Street through a back alley on the way to pick up some groceries. His daughter, Michelle Billingsley, told Denverite that her mother started to worry when he didn't promptly return. She poked her head into the alley and found him on the ground, badly bleeding and still being mauled by a neighbor's pit bull. It had jumped over the fence to attack him.

Michelle said the incident put her father in the hospital, and he couldn't walk for some time after he came home. While the bites on his arms and legs eventually healed, she said he suffered from aches related to the attack for the rest of his life. And not all the effects were physical.

"He never was the same," she said. "I don't think he ever went in that alley again."

City Councilwoman Mary DeGroot sponsored the measure with Councilwoman Ramona Martinez. She told us she didn't recall the Wilbur Billingsley's story, but she did remember visiting a house in the west side of the city where a three-year-old was killed by a pit bull.

"I remember driving by the house before we voted," she said "I just wanted to see where it actually happened."

Bentley's lawsuit was unsuccessful in repealing the ban, but it did force the city to extend a deadline that allowed pit owners to register their dogs. Those who qualified could be grandfathered into compliance, but it required $100,000 in liability insurance, proof that the owner was older than 21, proof that the dog had been neutered, proof it was vaccinated for rabies, and an annual $50 fee in cash, check or money order. A grandfathered pit bull also had to be marked as approved, sometimes with tattoos, and "confined" to its owner's property, kept inside or "behind an eight-foot fence (requiring Zoning approval)."

"Pit bulls go underground" - Rocky Mountain News, June 11, 2005

In 2004, Colorado's state legislature outlawed breed-specific bans, and Denver was forced to put its ban on hiatus. It lasted about year, until the state Supreme Court ruled that dog breeds were a singularly local issue, and thus the city had a right to ban pit bulls under "home rule" authority.

There was panic after the law went back into effect. People had apparently begun adopting pit bulls again - or at least brought them out of the closet - and suddenly pit lovers sprung into action to protect the dogs.

In 2005, the Rocky Mountain News ran a full-page spread of stories about people dealing with the reborn ban. In one, a brindle pit named Zena had been "haunted for nearly a month by the possibility of a death sentence." She was rescued by an organization called the "Pit Bull Underground Railroad," a "network dedicated to secretly ferrying the dogs out of Denver before animal control officers could confiscate them."

Many pits like Zena were taken to the town of Divide, west of Colorado Springs, to live on a 43-acre animal sanctuary.

"I consider this a crisis," sanctuary director Toni Phillips told reporter Jeff Kass. "You do what you have to do to save lives."

Another story in the spread said about 150 pits had been euthanized with lethal doses of sodium pentobarbitol in the month since the ban was reenacted.

Doug Kelly, director of Denver Animal Control at the time, told the Rocky that "the controversy" over the killing was "at a zenith."

"Every day the staff gets e-mails and phone calls from the outraged populace," the story read.

"We're compared to Nazis," Kelly told reporter David Montero.

One Rocky story described a woman who hid her dog in a basement. Police officers watched her back door as their colleagues tried to search the house.

But, Denver Post writer Kris Hudson printed that year, "City Council won't budge."

Despite a loud advocacy campaign to lift the ban, Councilwoman Rosemary Rodriguez said she was "unequivocally" opposed to overturning it.

Part of the repeal effort included a voice from actress Linda Blair, "best known for portraying the demon-possessed girl in the 1973 film 'The Exorcist,'" who "called publicly for Denver to lift the ban."

This outraged Councilman Charlie Brown, who said: "I'm not going to let a Hollywood star influence pit-bull public policy in Denver."

The ban was challenged one more time before the latest attempt by city council to repeal it.

In 2008, three Denver women sued the city, alleging that the ban unconstitutionally violated "their procedural due process rights" and was "unconstitutionally vague."

The women ultimately lost the lawsuit, but the city was forced to present the ban's merits in a separate hearing, something attorney Steven Rosenthal said was a "technical victory."

Through it all, the same arguments have persisted on both sides

Back in 1989, the Rocky Mountain News interviewed a panel of people about the ban.

On one side was Pat Andreason, president of the Colorado Dog Academy: "The problem is aggressive dogs attacking people. It's not a breed of dog."

On the other was Sterling Drumwright, director of Denver Environmental Health: "I'll tell you what the difference is between pit bulls and other breeds: They have lower levels of fighting inhibition; they have a tendency to attack without provocation because they're bred to do that. They will continue to fight until after they're dead or exhausted."

In 2005, City Councilwoman Carol Boigon told the paper the ban was "a strategy ... for managing a breed that is being encouraged not to be its best self."

"It's not inherent in the breed," Rosenthal, the attorney who fought the ban during the 2008 case, told Denverite. "It's inherent in the training combined with its physical capabilities."

And then, in 2020:

"I was thrilled that Mayor Hancock vetoed pit bulls as pets in Denver," Susan Walton emailed us. "Pit bulls were bred for hundreds of years to take down prey by the jugular."

And Olivia Lautin wrote in with the age-old counterpoint: "I think it should be repealed! I don't think the dogs are to blame at all, I think it's the humans! And the fact that we ban a certain breed makes absolutely no sense. They should ban people from getting dogs if they're not going to train them properly."

One thing is for sure, Rosenthal said, thinking back to his time in the fray: "It's true. At the time, the city felt very strongly about this. On both sides."