Updates with details from Friday's ceremony.

As a child, Olivell Owens wondered about the water under the "whites only " sign. Did it taste different than what flowed from the fountains where she and other African-Americans were supposed to drink in her hometown of Conway, Arkansas? She crossed the color line for a sip.

Her fearlessness didn't end there. When a white boy taunted Owens with a racist slur one day, she didn't hesitate to slap him.

Her mother, convinced Owens's bravery would get her killed, decided to move the family out of the south, first to Iowa before eventually settling in Colorado.

It was in Denver in the 1940s when Owens, then a teenager, met Dr. Justina Ford. After relating her stories of Arkansas to Ford, Owens recalls the doctor sharing her experiences of practicing medicine in Denver even though racism kept her out of the Colorado Medical Society and Denver General Hospital, now Denver Health, barred black patients and physicians.

Ford, Denver's first licensed black woman doctor, never sounded bitter or sorry for herself, Owens recalls. "She just told me how life is. It was like, 'If I made it, you can make it.'"

Ford died in 1952 at the age of 81, having treated patients almost until her death. Memories of Ford from surviving patients and friends are brush strokes in her personal monument, a people's history of Five Points.

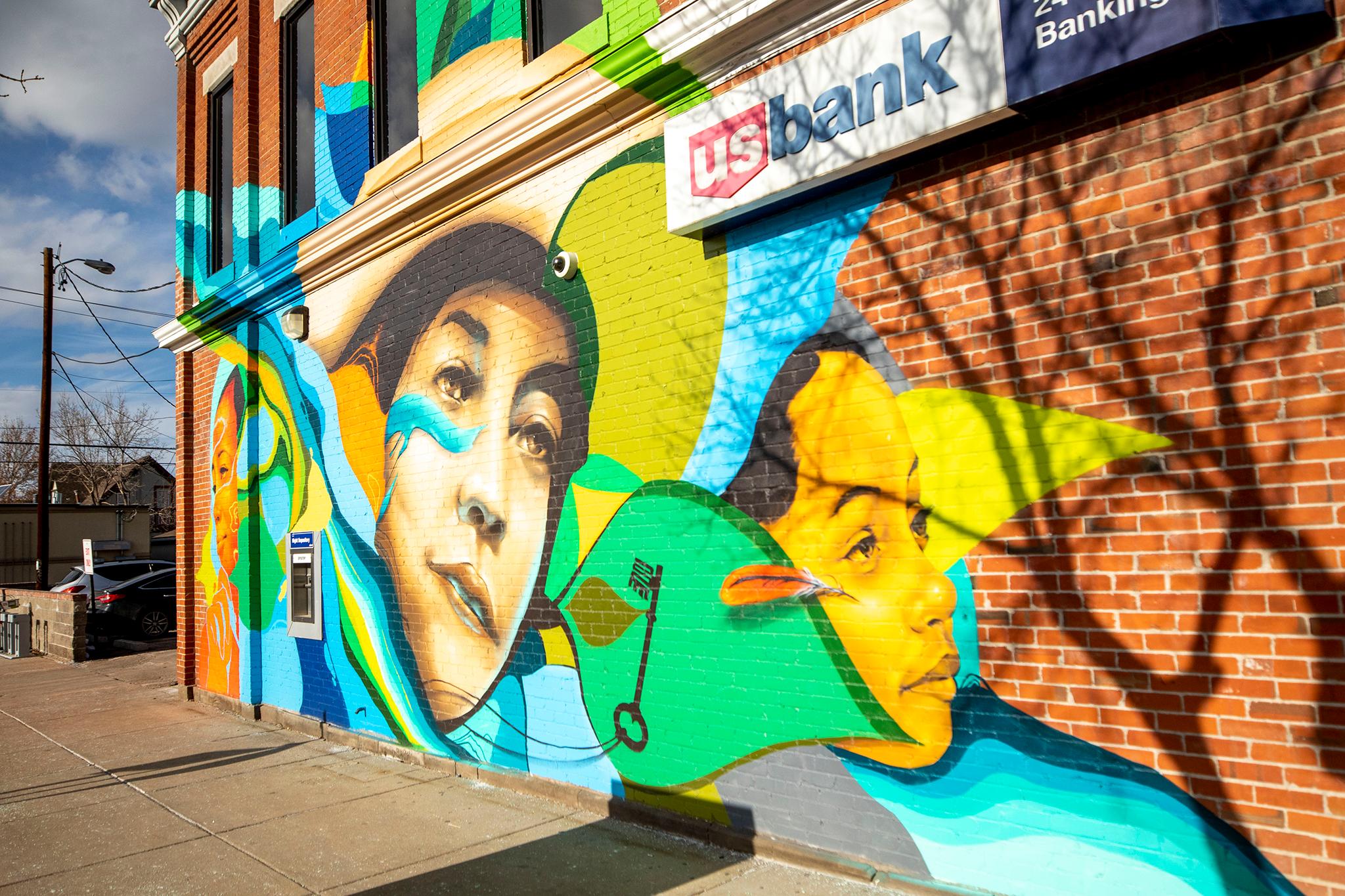

Owens joined others who knew Ford at a dedication Friday of a mural celebrating Black History Month and honoring the doctor. Mayor Michael Hancock awarded Ford a posthumous city honor during the ceremony, giving the gold Challenge Coin to Daphne H. Rice-Allen, who chairs the board of the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center. The award is usually given to living Denverites. Past honorees have included the late Marie Greenwood who was the first African-American school teacher within the Denver Public Schools

Connect for Health Colorado, the state's health insurance marketplace, commissioned Max Sansing to paint the mural on a wall of the U.S. Bank branch at 2701 Welton Street. The bank isn't far from 2335 Arapahoe Street, where Ford lived and treated patients. While Ford's two-story brick home was moved in 1984 to save it from demolition, the structure, now at 3091 California Street, houses the Black American West Museum & Heritage Center.

After training as a doctor in Chicago, Ford worked briefly at a hospital in Alabama. She arrived in Five Points in 1902, then the heart of Denver's African-American community as well as home to immigrants from around the world, many of them poor. Ford learned languages to better care for her patients and accepted payment in food or a skills exchange. Toward the end of her life, Ford estimated that she had attended the deliveries of more than 7,000 babies.

Mary Marquez says the woman known as "the baby doctor" was her family's physician.

Marquez was born in Tucumcari, New Mexico, 83 years ago and moved to Denver when she was five. Her father, Johnnie Martinez, had come first, finding work in a packing house. "Which was pretty common back then; people got jobs in packing houses and the rail road," Marquez says.

He bought a home at 2821 California Street before sending for his wife, Josephine, Marquez and their two other, younger children. In Denver, the Martinezes would have four more children.

Marquez says few other Mexican-American families lived in Five Points at the time. But she recalls that many other ethnic groups were represented among their neighbors.

Her brother Carlos Martinez, 81, lives in a high-rise complex for seniors in Sloan's Lake. He remembers teaching his Five Points playmates to say "caballo" during games of cowboys and Indians. A friend of his father stood out.

"He was the tallest Japanese guy I'd ever seen," Martinez says, smiling.

Marquez says that when her children were growing up in Denver, they would have had to be bused to experience the diversity at school that she witnessed as a student at Gilpin, Sacred Heart and Manual, which were all walking distance from her home.

In 1960, Marquez and her husband, Lee, bought the Westwood bungalow where they still live today. Their front room is decorated with photos of their children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren, most of whom also live in Denver. A granddaughter lives next door with her family.

"Every culture lived" in the Five Points of her youth, Marquez says. "To me, that has always been special. We all got along, the Germans, the Japanese and Spanish people that lived there."

Ford treated the Martinezes for illnesses such as measles and tonsillitis. She even cured Carlos of a stubborn ear infection and eczema after other doctors tried and failed. As payment, their father, who was a handyman and plumber, did odd jobs at the doctor's home. He also drove Ford when she made house calls to other families.

"We were all friends. We were all neighbors," Marquez says. "We were all poor. Nobody had any more money than anybody else."

When Ford came to the Martinez home to deliver Marquez's youngest brother on Oct. 13, 1948, she instructed Marquez to ready a pan of not-too-warm water and a towel. Then Marquez was entrusted with the baby's first bath.

"It was like washing a little doll," Marquez recalls.

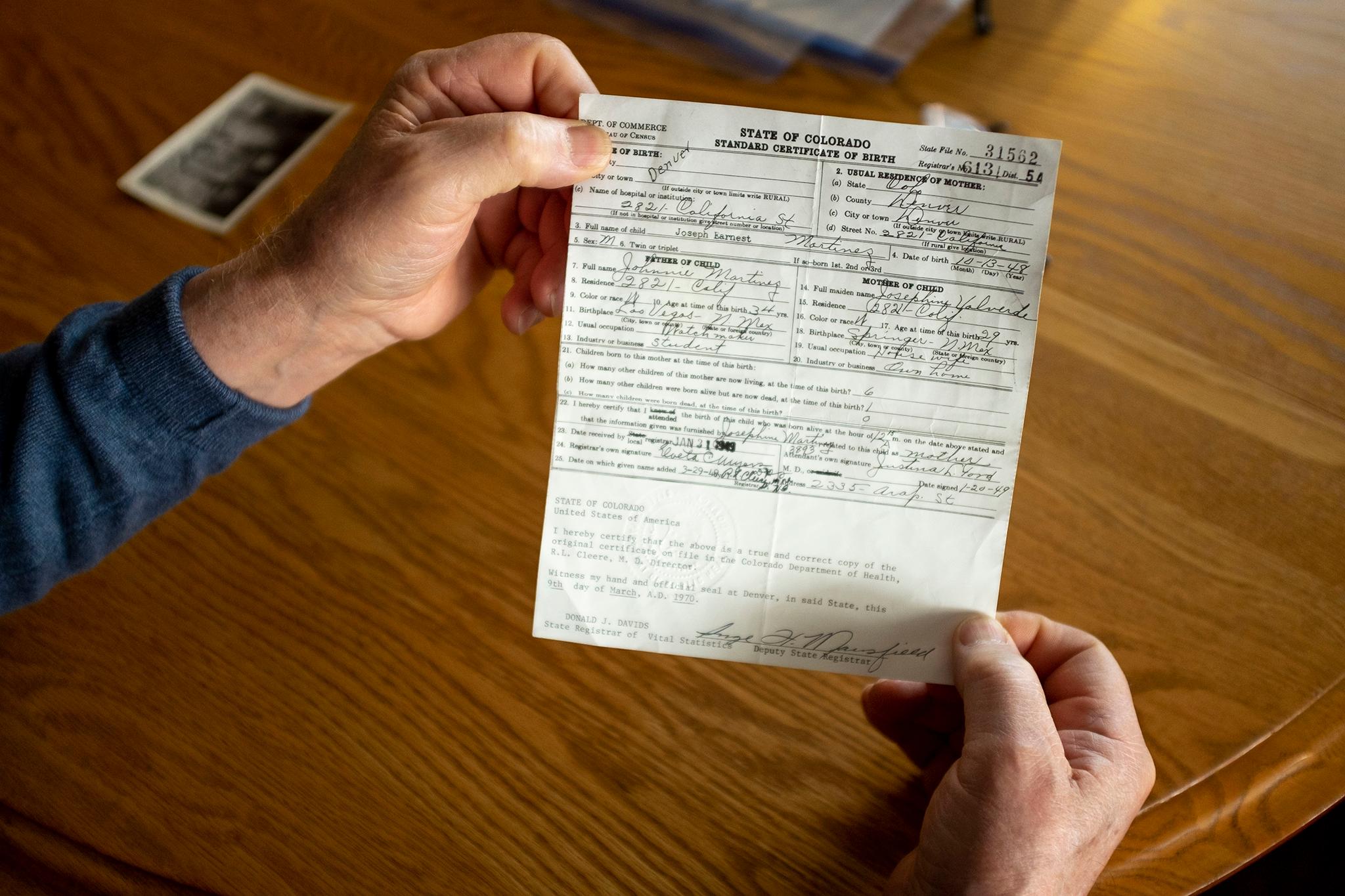

Joseph Martinez, 71, had just turned 4 when Ford died. He grew up hearing about the doctor, but never thought much about being a Ford baby until he heard a news story about her during Black History Month last year.

"I thought, 'That name sounds familiar,'" he says.

He pulled out his birth certificate and found Ford's neat signature. Then he took a copy of the birth certificate from his home in south Denver to the Black American West Museum & Heritage Center. He says he cried as he talked to a museum volunteer about Ford.

"She was just determined to help people," he says. "I get emotional talking about her. Her story and being part of that is really touching to me."

He calls Ford "the Mother Teresa of Five Points."

"There are a lot of people like that that need to be recognized," Joseph Martinez says. "It's not about me. It's about her and what she stood for."

His mother died the year after Ford. Josephine Martinez was just 34. Her children remember her as often bedridden.

"She never wanted to go to the hospital. She only wanted Dr. Ford to treat her," Marquez says.

Terri Richardson, vice chair of the Colorado Black Health Collaborative and a Kaiser Permanente internist, has heard other such stories of the trust patients placed in Ford.

"People are still proud to say she was their doctor," Richardson says. "She served a vital role. Would these people have been served any other way if she hadn't done it?"

The collaborative is a nonprofit working to connect black communities, which have traditionally been under-served by health professionals, to proper care. It has worked with Connect for Health Colorado to ensure African-Americans have access to health insurance, and the collaborative holds workshops on such issues as diabetes and breast cancer in barber shops and salons, embedding itself in neighborhoods as Ford did.

"She worked for way more years than I'll be able to work," Richardson says. "Would I have been able to stand that strong for so long?"

Retired Denver pediatrician Dr. Renee Cousins King wonders whether Ford had other doctors to whom to turn to discuss cases. She says doctors in the hospitals that barred Ford would have missed out on her experience and perspective.

Ford attended the birth of King's father, prominent Five Points businessman Charles R. Cousins. King grew up hearing stories of Ford, including an account from a nephew of Ford who had accompanied his aunt on a house call. As they left the home, Ford turned to her nephew and said:

"Those people are hungry."

She sent him to buy groceries for the family.

"That's a very kind, very realistic, very important way to help people," King says.

"I think it's very important to preserve the history of Dr. Ford and the Black American West Museum," King says. "And you start with the house. That museum would not be as compelling if it were in a structure built 10 years ago."

Ford was never able to practice at Denver General and was accepted into the Colorado Medical Society two years before she died.

Marquez says she didn't know until she was an adult that Ford had been barred from Denver's hospitals.

After her mother's death, Marquez's father asked her to stay home to help care for her younger siblings rather than go to college and pursue her dream of becoming a Spanish teacher. But years later, when her own children were old enough to be at school all day, she earned an associate's degree in Spanish at Metro State. She says her language teacher in college relied on her to help the other students with conversational Spanish. Marquez has also worked as a receptionist for Denver Health and for the city's police department, owned a small shop on Morrison Road, and coached young golfers and softball players.

"I taught all my grand kids to play golf," Marquez says. "I got to be a teacher anyway."

Owens, the Arkansas transplant, was pregnant when she arrived in Denver and sought Ford out because she wanted a woman doctor.

Ford did not tell Owens until she was delivering that she was going to birth not one, but two babies. Owens believes Ford was worried that it would be too stressful for such a young mother to know she was going to have twins.

Owens was kicked out of school after officials discovered her pregnancy, and her mother was angry that her only child was becoming a parent so young. But Owens found a mentor in Ford, confiding in her that she wanted to become a surgeon. Owens says she and Ford even talked about opening a school for teen mothers to ensure pregnancy did not keep young women from fulfilling their dreams.

"She just respected me," Owens says. "She was my friend. That's what it was. I just didn't realize it then."

Owens was 14 when she married the father of her twins on Dec. 10, 1945. Her daughters were born Feb. 14 the next year. She plunged into domestic life, and after Ford died a few years later, her aspirations of studying medicine and opening a school were put aside.

But Owens went back to school at 19 and earned the equivalent of a high school diploma. In her 40s, she went to night school to train as a nurse's aide and later as a beautician.

Ford "told me that it was hard for her to get her education," Owens says. "She let me know that I needed an education."

Charlotte Mozee, one of Owens's twin daughters, was killed at the age of 28 in a domestic violence dispute. Charlene Mozee, who is younger than her sister by just a few minutes, says seeing her mother return to school was instrumental in her own life. Charlene has a nursing degree and says she recalls hearing stories about Ford from her mother. The two were interviewed together in Charlene's East Colfax home. Owens lives with a younger daughter in Aurora.

"I knew her character and her struggles," Charlene says. "I'm sure Dr. Ford had a lot to do with the way I felt about a lot of things."

Charlene recalls a patient at a nursing home where she worked once telling her she was surprised the facility had hired a black nurse.

"I thought about Dr. Ford and I asked, 'Don't you think that if I go to school and meet all the requirements, I should get a job?'"

She says the patient begrudgingly agreed.

The Black American West Museum & Heritage Center would like to hear from more people who were treated by Ford or at whose deliveries she attended. If you are a Ford baby or patient, contact Sylvia Lambe at [email protected] or 720 276 3880.