Dorothy Spencer was born a few years after the 1918-1919 virus pandemic.

"My mother told be about the one in 1919," Spencer said. "It didn't really sink in that much until this one came up."

Spencer remembers her mother saying that the family lived through it on their Illinois farm.

"I imagine they pretty much stayed on the farm by themselves," Spencer said. "When you lived on a farm, you were pretty much isolated."

In 1918-'19, an H1N1 flu virus infected some 500 million people, a third of the world's population at the time. At least 50 million worldwide were killed, about 675,000 of them in the United States.

Since reports started to emerge in December that a new coronavirus was sickening people with COVID-19 in China, around the world more than 600,000 people have been infected and, while most cases are mild, the disease has killed more than 29,000, according to the World Health Organization. The United States has confirmed more than 122,000 infections and more than 2,000 deaths, including more than 2,000 cases and some 40 deaths in Colorado.

Experts have advised older people, who are especially at risk of falling seriously ill if they are infected by the coronavirus, to stay inside and away from others during this new pandemic. While her mother had her family with her on the farm, Spencer, a widow who will soon be 99 years old, is alone in the Virginia Village home that she and her husband bought 55 years ago and where they raised their three children. Her husband ran a beer wholesalers' trade group and she was his secretary. He died a few years after they retired together when they were in their 70s.

Knitting helps Spencer stay connected to others.

When a nextdoor neighbor phoned to ask if she needed anything, Spencer asked her if she could pick up a supply of yarn so she can keep knitting stocking caps for people experiencing homelessness, something she's done for years.

"I just have my family pass them out," Spencer said. "As I get stocking caps knitted, I give them to my family, who are more active than I am."

Relatives also keep her stocked with food, placing it on the porch for Spencer to bring inside.

"I can still cook," she said. "I don't cook very much."

The porch has become a buffer zone. Spencer leaves her laundry there for a granddaughter to collect and wash before returning it to the porch. Spencer sends her terrier, Skylar, to the porch to be picked up by neighbors for walks.

Skylar is "a good little dog and smart," Spencer said. "She keeps me company."

Neighbors and relatives also keep her company, usually by phone.

"I have good neighbors," she said.

Even before the coronavirus, Spencer had not gone out much in recent years. Back trouble had kept her from walking outside, but she exercises on a treadmill in her home.

"I do the treadmill every day to keep active," she said. "My health's pretty good for an old person."

"Right now, everybody doesn't want to go any place," Spencer said. "I don't know how long this is going to last."

While withdrawing is keeping them physically healthy, being cut off could put undue mental stress on seniors.

"What do they do to punish you, to really punish you, in jail? It's isolation," said Jacqui Shumway, a tai chi instructor who has many older students.

Shumway is working on an online version of her classes. She and her husband, Joseph Brady, own the Colorado School of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the City Park West neighborhood and have long focused on research into aging. Shumway said she understood the public health reasons for keeping older people away from others during the coronavirus outbreak. But she worries about the effect on seniors' mental health, especially those who live alone, and whether they will be able to rebound when the crisis is over.

Shumway urges people to keep in touch with their older parents, by phone or online, as she does with her 83-year-old widowed mother, who is in an assisted living facility in Texas. And Shumway encourages seniors to calls friends and relatives for the sake of their own and others' mental health.

Jayla Sanchez-Warren, who directs the Area Council on Aging for the Denver Regional Council of Governments, has a network of people who pay regular non-medical visits on seniors, though she has suspended in-person check-ins because of the coronavirus. She told Colorado Public Radio she's now relying on phone calls two or three times a week to see whether clients need someone to deliver food or supplies, and to let them "know that somebody cares."

Some people, like Spencer, have regular contact with neighbors, friends and relatives.

But "there are some that are pretty isolated, and that's who we focus on," Sanchez-Warren said.

The public and private sector has also found ways to help. Members of Denver City Council and the Denver delegation to the state legislature have adapted the phone bank, a staple of election campaigns, to organize volunteers to call older constituents to check that they are safe and healthy. Senior Planet, a national nonprofit that helps older Americans engage with technology, has compiled a coronavirus resource guide with links to virtual fitness classes and online support groups, saying "social distancing doesn't mean you have to be alone." Dale Elliott, director of aging and nutrition services for Volunteers of America Colorado, has talked with his staff about dropping off puzzles or mind teasers along with Meals on Wheels to help seniors "get past this isolation period."

"It's much more than a meal. It really is much more than a meal," Elliott said.

The coronavirus has forced changes in Meals on Wheels. Volunteers leave food at doors and return to their cars to wait and watch to see that recipients take the parcels inside.

"There's been a lot of waving," Elliott said. "We're still checking in with them, making sure they're OK."

Regular gatherings in the Meals on Wheels congregant dining program have been canceled, and meals are being distributed in packages that participants can take to their homes to eat. Many other social events for seniors have been suspended.

Elliott said volunteers, particularly those who helped organize the congregant dining events, often were seniors themselves. Because those volunteers are being advised to stay in, Volunteers of America has put out a call for new volunteers and turned to other organizations to help deliver meals, Elliott said.

Volunteers of America isn't alone in having had an army of senior volunteers.

Food pantries and shelters are among places that have had to scramble to fill a void because the coronavirus has sidelined helpers.

Debbie Fox has taken to her social media network to try to fill the gap at the Denver Rescue Mission, where she had for years volunteered in the kitchen, preparing meals for the men who spend nights at the mission's shelter on Lawrence Street.

"I'll be honest, it's sad not to be there," Fox said. "I really enjoy having that nice chef's knife in my hand, chopping fruits and vegetables."

At 64 and after having recently had a kidney removed, she felt it would be irresponsible to risk her health by continuing to volunteer. Fox was active in a book club and often went to dinner with friends. The members of the club and her social circle also are older and have been staying home. She's had to give up Latin dancing.

Fox has found that people are coming together in other ways. She video chats with her granddaughters in Missouri and calls her mother in Michigan. Fox, whose husband died of cancer seven years ago, participates in a Facebook support group for widows.

"We're all rallying around each other," said Fox, a retired event planner.

Cycling and walking the trails near her Arvada home help her maintain mental balance, she said. She's been out on the trails with a friend, who kept the six-foot social distance health experts advise (even more than six feet, Fox said, because her friend had a dog who kept running ahead).

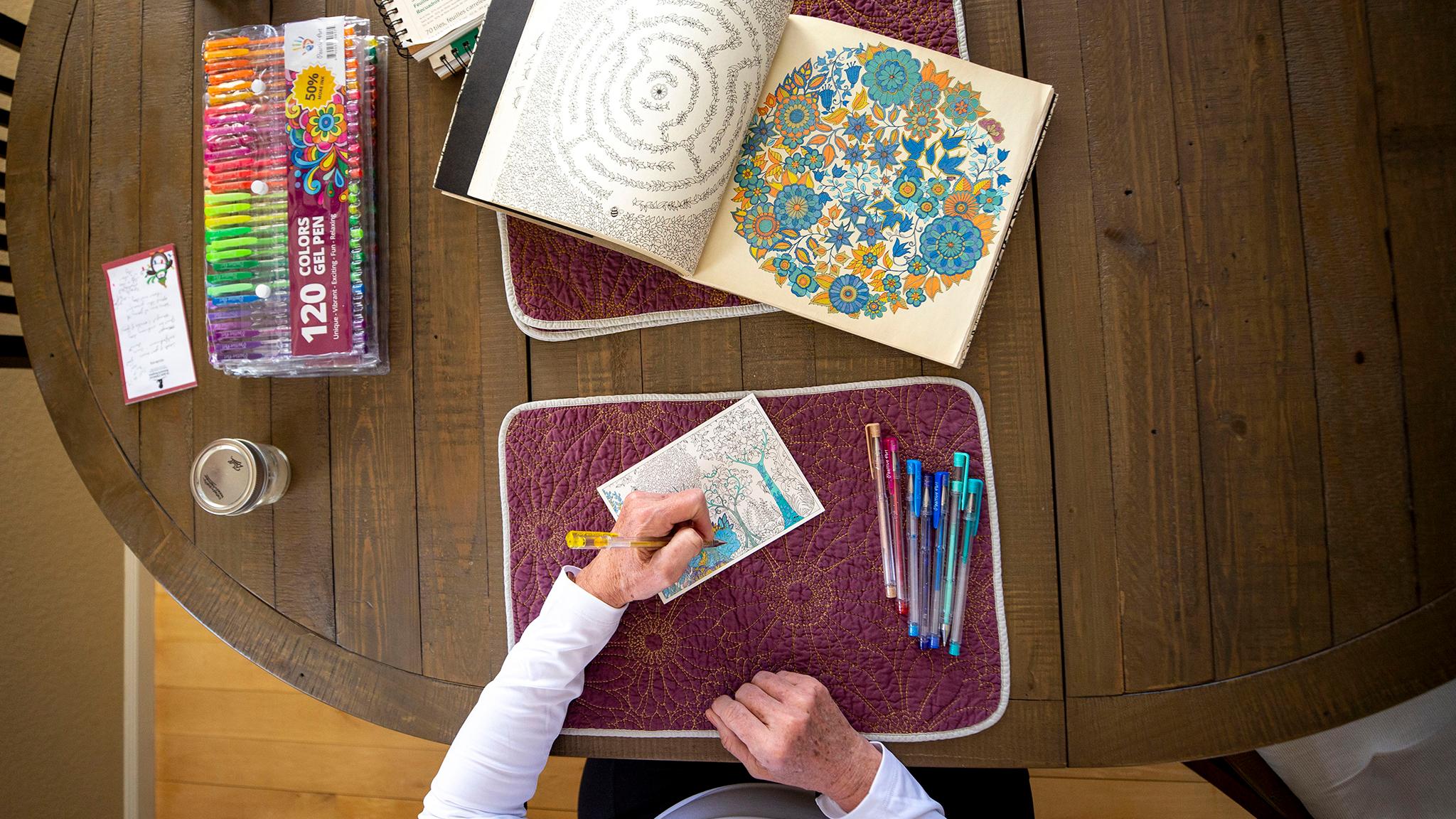

Fox also relies on yoga, meditation and art.

"I don't feel panicked," she said. "I'm beginning to see the beauty in this situation, in how people are responding and coming together."

And she's looking forward to returning to the Denver Rescue Mission kitchen one day.

"It filled me with a sense of purpose," she said. "It provided me with a sense of belonging."