Fentanyl-related overdose deaths in Denver tripled between 2019 and 2018, according to data from the the Denver Department of Public Health & Environment and the Office of the Medical Examiner.

Fifty-three people died from overdoses involving fentanyl in 2019 -- triple the amount from 2018, when it was 17. The city had 18 fatal overdoses involving fentanyl in 2017.

As of March 22, the city has had at least 10 deaths involving fentanyl this year.

Overall drug-related overdoses have remained nearly the same year over year. In 2019, 213 people died in Denver from drug-related overdoses, up slightly from 209 fatal drug overdoses in 2018 and 201 in 2017. (While the data shows that fatal drug overdoses have increased annually between 2015 to 2019, fewer people are dying per capita year over year.)

"I am really concerned about the fentanyl deaths," Harm Reduction Action Center executive director Lisa Raville said. "Of course it was going to come here, but my goodness."

Last year, most fatal drug overdoses in Denver involved multiple substances.

Fifty-four percent of deaths had three or more drugs present, while 18 percent involved five or more. Opioids -- a class of drugs including fentanyl, heroin, morphine and hydrocodone -- were found in nearly 60 percent of drug-related deaths in the city.

Medical examiner office spokesperson Steven Castro said its new case management system can now capture more than five substances found in deaths.

"So if there are 15 drugs in a (person's) system, we are able to capture 15, just as an example," Castro said.

At least 25 percent of drug-related deaths in Denver included fentanyl in 2019, compared to just 9 percent in 2018.

CU Skaggs School of Pharmacy professor Rob Valuck said fentanyl can be up to 100 times stronger than morphine.

Fentanyl is used for medical purposes in small quantities. But when it's used outside that setting, Valuck said it's usually cut into heroin.

"If it's used outside medical use, it's just extremely potent," said Valuck, who also directs the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention. "It's really troubling, obviously, because it doesn't take much of it to kill (a person)."

Sixty-seven percent of fatal ODs happened in residences, while at least 17 percent happened at hospitals. At least 8 percent happened outdoors, while less than 2 percent taking place in businesses. At least 15 percent of people who died from drug overdoses were experiencing homelessness.

The data includes information about "place of injury," or where a person who overdosed consumed a drug or was found. "Unknown" accounts for 43 percent of these locations, while "home" accounts for 45 percent. Castro said a death occurs at an "unknown" location when officials can't pinpoint where that person took the drug or where they came from.

"We always know where they died, but we don't always know where they consumed the drug," he said.

Raville, whose organization provides a needle exchange program and other services for drug users, said she wants clearer data. She notes the place of death may not give a full enough picture for someone who overdoses, and she thinks some people aren't actually dying at hospitals, as the data suggests.

Ann Cecchine-Williams, deputy executive director for the city's public health department, said the city created an "early warning system" last year to alert organizations like HRAC if the city learns there's fentanyl in the city's recreational drug supply. Last year, Denver police issued a public warning after finding fentanyl in "brick-like form" for the first time in the city.

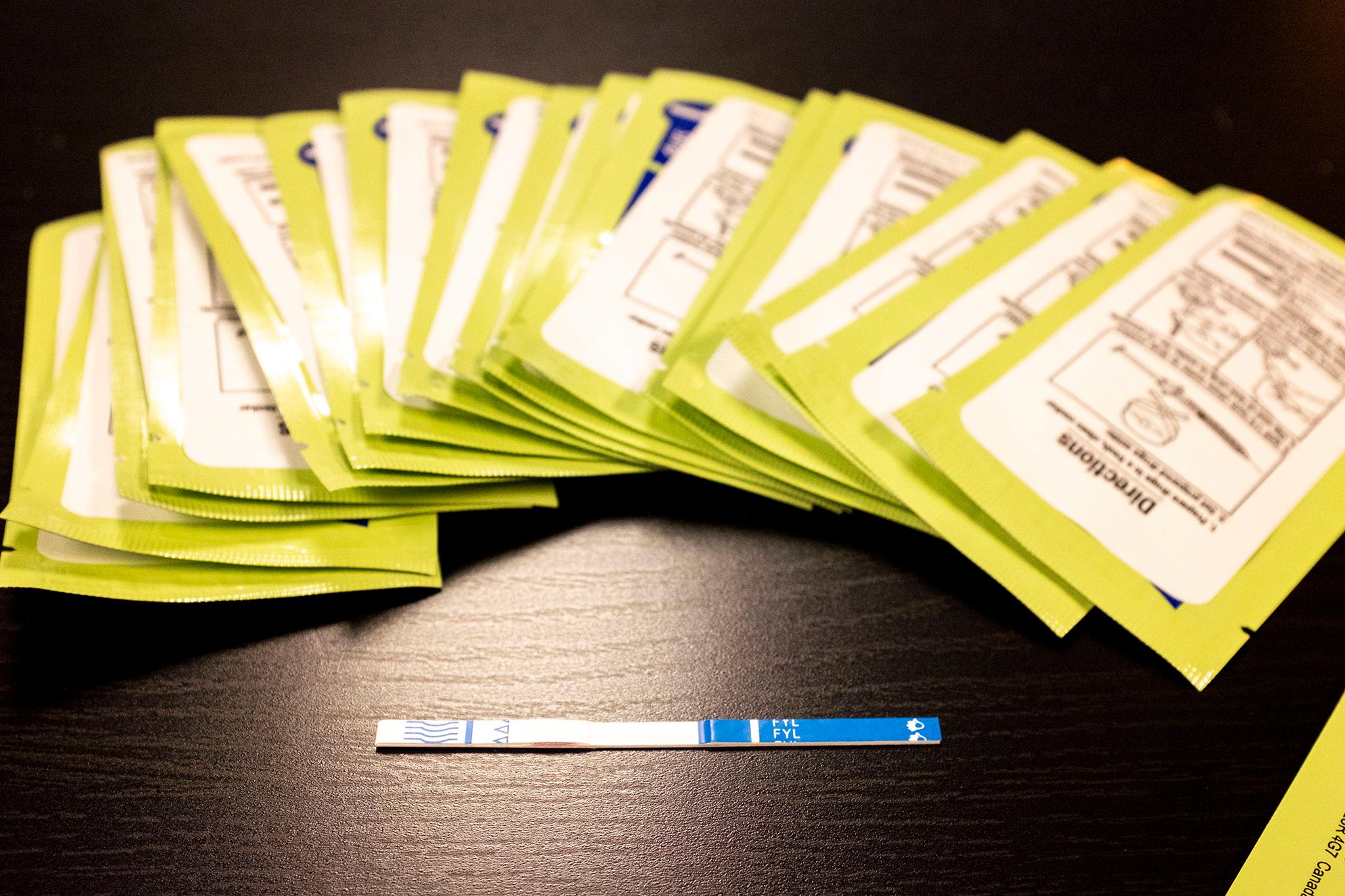

HRAC has provided fentanyl-testing strips for nearly two years, which Raville said are key in helping to reduce overdose deaths. The organization has trained 917 people -- including people who inject drugs -- to use naloxone, the medication that can reverse an opioid overdose.

So far, the training sessions are proving helpful: Raville said HRAC clients reported successfully using naloxone 514 times in 2019, saving hundreds of lives.

"We can do something about this," Raville said. "We've got to do better."