A Shakespearean tragedy that scholars theorize was written during an outbreak of the plague in London. A drama from the 1920s that explores themes of dehumanization and isolation. New plays that are comic with a dark edge.

Don't expect escapism when you go the the virtual theater of a quarantine-era Denver company that uses the video conferencing app Zoom as its stage.

"I don't want to distract people," said Bradley Abeyta, founder and artistic director of the COVID-19 Theatrical Response Team. "I want to help them process."

Abeyta, who describes himself a big Nuggets fan, said the idea for his virtual theater company came to him in mid-March, after the NBA suddenly suspended its season following news that a Utah Jazz player had tested positive for the coronavirus. Two days after the March 11 NBA announcement, Mayor Michael Hancock ordered city venues such as Red Rocks and the Denver Performing Arts Complex to close, and urged private businesses to do the same to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus.

"It felt like a fundamental shift was happening," Abeyta said.

In February, he had been working as an assistant director for "Frost/Nixon" at Aurora's Vintage Theatre. Abeyta had been contemplating a shift of his own, from primarily acting and stage managing to more directing.

He wrote an email describing his goal of offering opportunities for "creative people to keep stimulating that part of their brain."

Responses arrived almost immediately from about 10 people, most of whom are still involved. The COVID-19 Theatrical Response Team, a volunteer project, has grown to some 60 actors, writers and directors.

The team presented its first show at the end of March. Since then, audiences at home have been live-streamed at least one play a week from actors in their homes, among them "King Lear," which Shakespeare may have written during a plague, and 1923's "The Adding Machine" by Pulitzer-winner Elmer Rice.

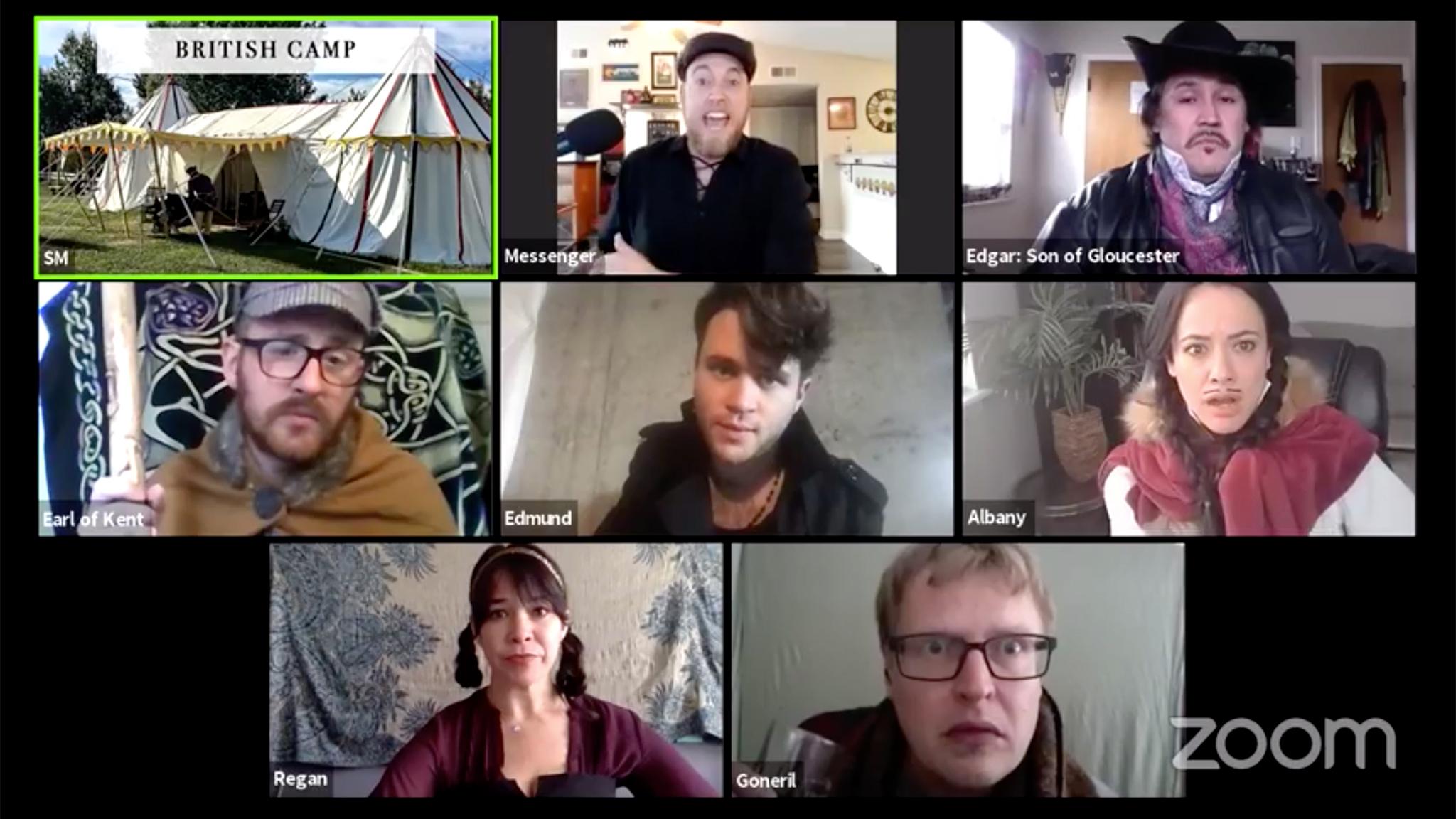

Early COVID-19 performances look like staged readings, except instead of sitting together around the table, the actors appear each in their own Zoom tiles (except in a few cases in which roomates were cast in the same show).

Over the weeks, the productions have become a bit more elaborate, with actors moving from room to room and scenes set by the occasional photograph of a castle or other site.

Dan Rib runs the meetings that are the COVID-19 Theatrical Response Team's shows. His day job is production manager for the 400-seat Elaine Wolf Theatre at the Staenberg-Loup Jewish Community Center in the Washington Virginia Vale neighborhood. Rib had just started to use Zoom for office meetings when he came on as Abeyta's technical director.

"I literally just Googled, 'What's the best online meeting platform?'" Rib said.

He bought a Zoom subscription and dove into online tutorials in preparation for the project's launch. Rib has stage managed large shows and appeared on stage himself. Even though it was largely a friends and family event, he said he had never been as nervous as when he connected and hit the "live" button on March 26 for the first COVID-19 Theatrical Response Team production. It was Terrence McNally's "Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune."

Actors and directors are working from their homes on phones and computers that are of varying ages and levels of sophistication. Anyone's WiFi might drop at any time. After Rib's own computer overheated during one rehearsal, he convened a meeting during which he forced his computer to stop and discovered that the show went on without him.

The potential for the unexpected to occur and the need to be able to solve problems on the fly makes virtual theater feel "very much like live theater," Rib said.

He said that since the debut of the COVID-19 Theatrical Response Team, brick-and-mortar theaters in the Denver area have consulted him about how they can move online. He's also helping fitness trainers and others at the Jewish Community Center develop virtual classes.

"I don't feel like I was restricted during this quarantine," Rib said. "I feel like I expanded my social network and my professional network."

Abeyta's team encourages use of the "chat" function, perhaps the opposite of shushing audiences in a theater, hoping viewers will feel they're part of a community even if they are not in the same room with one another and the actors. Actors might even cross the digital fourth wall to respond to audience comments.

"We've just reinforced the idea that social distancing does not mean that we're isolated," Abeyta said.

At the start of each free performance, viewers are urged to contribute to the Denver Actors Fund, which has created an emergency fund to help theater artists whose earnings have been hurt by the pandemic.

Alaina Beth Reel, an actor, director, teacher and writer who's appeared on stage at Curious Theater Company and the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, has been helped financially by the actors fund and other grant makers since COVID-19 darkened stages. And she's found inspiration in Abeyta's virtual theater company.

The stripped down productions for Zoom are "a chance to really just make it about the people and the emotions and the story," Reel said.

Among other contributions, she helped organize a festival of plays written for Zoom and directed one of those pieces. The festival, she said, "made me want to keep writing and telling my own stories from this period that we're in."

"There's a lot of questions about what it means to be connected and to care in big and small ways."

Then she laughed. Reel, who lives alone, said her coronavirus drama might not end up so serious: "It will be a play about a mouse in my apartment."

Like Reel, multimedia performing artist Cyndi Parr lives alone. The isolation and a cold she worried was COVID-19 got her thinking existentially.

"If we can no longer meet, how are we going to still tell these stories?" she wondered.

Then she got the email from Abeyta, whom she knew from a puppeteering group. Suddenly Parr, who lives in Colorado Springs, was virtually meeting with other story tellers.

"Usually distance has been a big barrier," Parr said.

She brought some of her original plays to Abeyta's project, saying she has found they suit the pandemic moment. In one, a comedy called "Heart of War," a couple takes as its marriage guide the "Art of War" by the military strategist Sun Tzu. Spouses who may be spending unprecedented amounts of time together because of the quarantine might find this bit of ancient advice useful: "The greatest victory is that which requires no battle."

Like technical director Rib, Parr plans to take lessons from her COVID-19 theater experience to her other work. When troupes can again be together, she said, as a director she might be able to offer an actor pressed for time the option of occasionally Zooming into a rehearsal. And she's planning a Zoom production of a summer play.

"I've been so appreciative of getting to connect with people across the state and rethink how we can do theater," Parr said.

The COVID-19 Theatrical Response Team went national for its theater festival.

Denver actor Curtiss Johns had been in touch with an old friend and colleague from Boulder who now teaches and performs in the Washington, D.C., area. His friend, Brian MacDonald, said he hadn't spoken to Johns in a decade when they reconnected to chat via Zoom amid the coronavirus outbreak.

"It took a pandemic to bring us back together," MacDonald said. "Community in general is important. I think it's more important now."

MacDonald and Johns hit upon the idea of a festival of plays about the pandemic and formed a partnership they call Dramatic Distancing to produce it. Johns made the introduction to Abeyta's COVID-19 team. Together, Dramatic Distancing and the COVID-19 theater project kicked off this month with a three-day festival of 14 short new plays.

"It was about people coming together, reminding each other we are not alone," MacDonald said. "I found it really encouraging and uplifting."

He and Johns contacted colleagues across the country -- some with whom they'd long lost touch -- to ask them to participate. Playwrights were asked to include a mention of toilet paper and the phrases "wash your hands" and "don't touch your face." The resulting festival was a reminder that though we are experiencing the coronavirus separated from one another, our experiences are similar. The scripts are so topical that watching the plays can feel like eavesdropping. In one, a character laments, "All my life is just Zoom meetings and putting out fires at work."

In another, set in the future, a character speculates that "there may never be another play performed."

Abeyta thinks performers and audiences eventually will return to theaters. Perhaps at first in the open air, where social distancing can be observed.

"I don't think there's any way that live performance will die," he said. "The desire for that connection is there."