Joel Hodge wears his experience with violence on his face. He's been shot three times, and one incident claimed his right eye.

He was released from a Colorado prison in 2001. He had met his wife, LaKeisha, on weekenders while he was still incarcerated. They founded their nonprofit and married as soon as they had the chance.

The Struggle of Love Foundation is their attempt to curb youth violence in northeast Denver. When shots are fired or gang activity picks up, Denver police leaders call Hodge, a Chicago native, to speak with families reeling from tragedy. He makes sure they have what they need, and he tries to talk mourning relatives down from retaliation.

Hodge says this summer will be a difficult one.

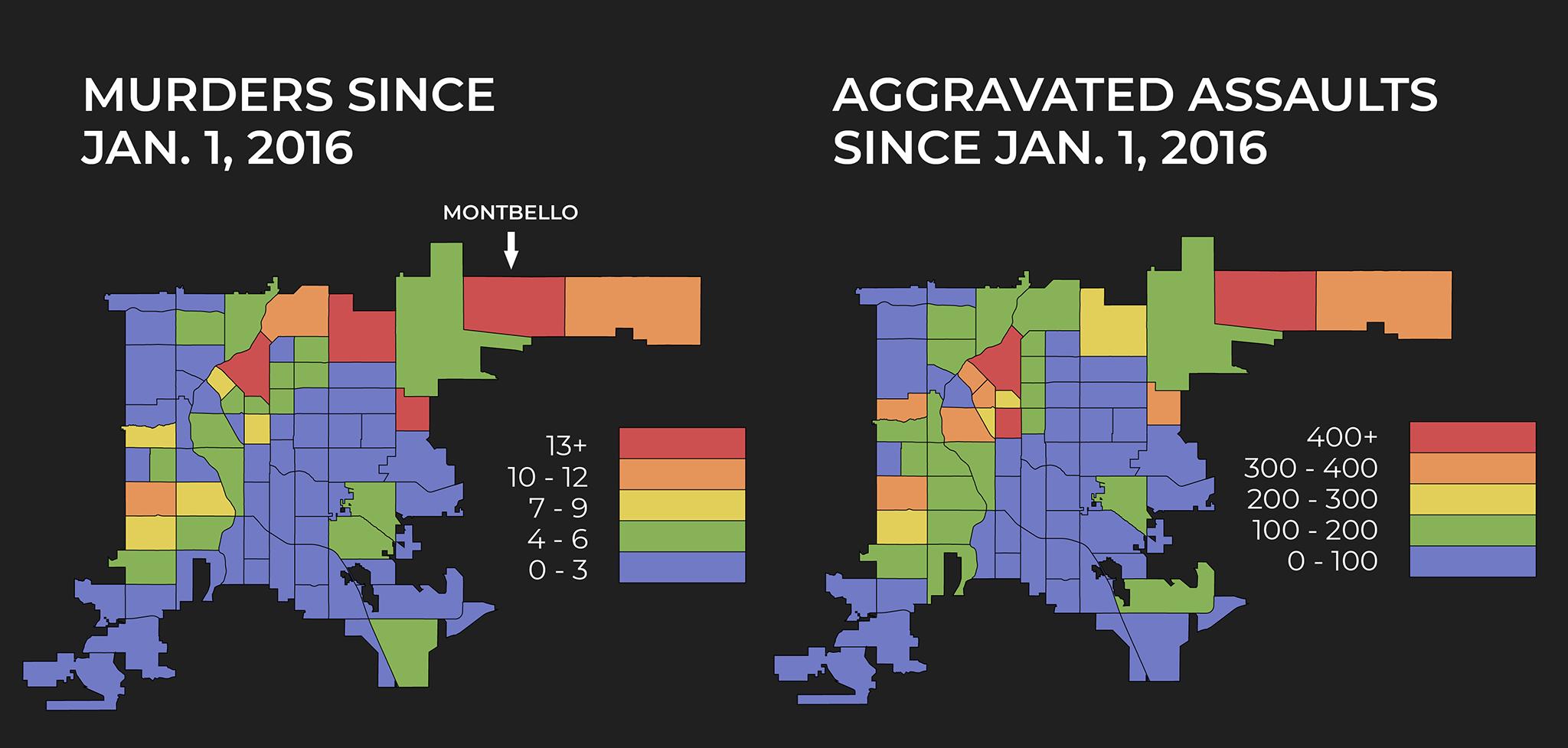

Violence always picks up in the summer, when it's hot and people spend more time outside, Hodge said. But he suspects the problem in Montbello and Green Valley Ranch will climb to new levels this year. Lock downs related to COVID-19 have resulted in high unemployment and people spending a lot of time in close quarters. He says it's a recipe for disaster.

"They're gathering at home. They don't have nothing to do. So, what we do? We drink. Let's be real," he said. "Once the drinking comes along, then comes up an argument. Next thing you know, we don't know how to do conflict resolution the right way. All we know is violence, because that's all we've seen growing up and that's all we've heard and that's what we adapted to."

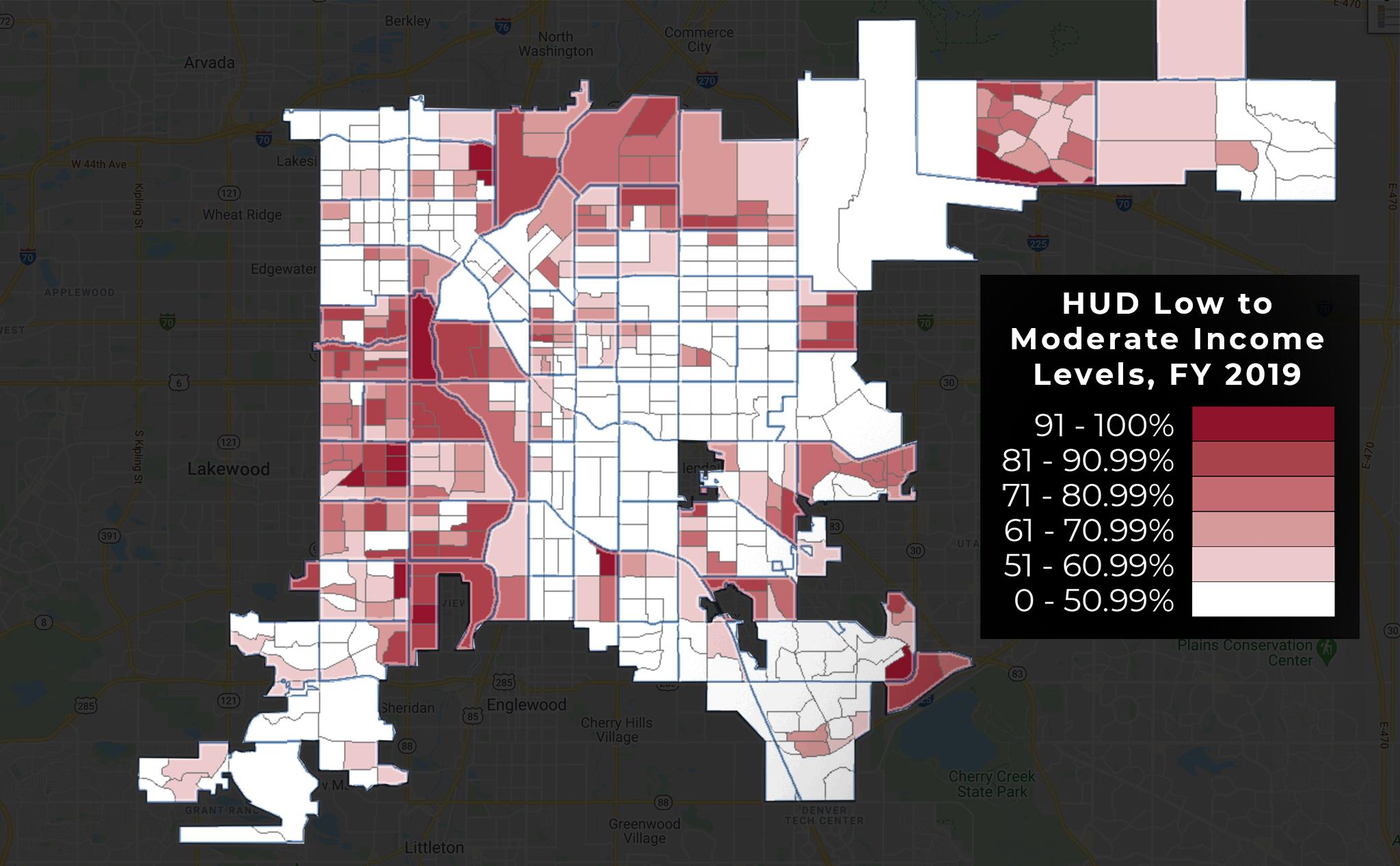

Generational and institutional inequalities have long festered in low-income communities like Montbello. The pandemic has laid bare longtime problems related to accessing education, healthy food and stable jobs.

It's why Hodge and his family are working overtime at their food pantry in Montbello, where they move truckloads of food into the hands of people in need every day. They've seen a tenfold increase in demand since the pandemic hit.

Hodge and others are doing their best to patch holes in broken systems. They hope it will be enough to hold their communities together as the world seems to be falling apart all around them.

Eris Griffin was shot in the back of the head when he was 20 years old.

He'd left a club off Leetsdale Drive when some men approached him. He was watching one of his friends run away when the shot went off right behind his ear. He hardly remembers the incident that changed his life forever.

"I just know dudes walked up on us, and after that I woke up in the hospital," he recalled. "I couldn't believe it really happened."

Griffin was unconscious for five days. It would take a half decade for him to fully recover, requiring assistance to walk and eat for years.

Today, Griffin is mostly back to his old self, though the bullet is still lodged in his skull. He still can't play basketball like he used to, when he thought he'd be a career player and foreign leagues sent him recruitment letters. He spends a lot of time now volunteering for Hodge, his brother-in-law, at the food pantry.

Griffin grew up in Montbello, and he says the neighborhood has changed a lot since he was a kid. He no longer knows everyone on the block where he grew up; most families from his childhood have moved away. He was one of the last graduates of Montbello High School before Denver Public Schools decided to phase it out in 2010 and replace it with three charter schools on the campus.

He remembers a homecoming dance in the school gym, where he played varsity basketball. Hodge lent him a white Cadillac to pick up his date. That night ended with girls fighting in the parking lot and police officers rushing in to break up the brawl.

Violence has followed Griffin throughout his life.

"A lot of things can be talked out. But a lot of people don't know how to communicate," he said. "A lot of people need love. Or they need guidance."

The issues Griffin experienced firsthand are things researchers at Montbello's Youth Violence Prevention Center, a program affiliated with the University of Colorado, have identified as factors that contribute to shootings and fights in the neighborhood. In 2017, they began a baseline study of residents' thoughts and feelings by knocking on doors and conducting lengthy interviews.

Dave Bechhoefer, the project's director, said the loss of the high school, the closure of Montbello's only full-service grocery store in 2014, and RTD bus route cuts in 2016 were all major burdens on residents. He said they show that the city's systems are not set up to benefit residents like Griffin and Hodge.

"The fact of the inequity causes a lot of anger," Bechhoefer said. "That ongoing glaring difference creates a lot of anger, creates a lot of self-doubt."

People who live in Montbello, like other Denver neighborhoods where the majority of residents are people of color, are less likely to complete formal education and are more likely to be displaced. These neighborhoods are mostly on the city's north and west borders, in what's been called the "inverted L."

While Bechhoefer defers to Hodge for predictions about the future of violence -- he calls Hodge "the expert on Montbello" -- Bechhoefer agrees that things could be worse this summer if Hodge and others can't ease some immediate pains. On top of everything else, the pandemic has canceled many summer programs where young people would otherwise find a safe space and supervision.

"It's totally going to be a volatile situation," he said. "Parents just cant drop everything and take care of their kids."

Jason McBride, who works with Denver's Gang Rescue and Support Project, described the situation like a classroom with a substitute teacher. Along with officials working to keep offenders out of jails, another measure to deal with the pandemic, he said people feel like they can get away with more than usual.

"You can do all the things you couldn't normally do when the teacher wasn't there," he said. "These kids know."

He's been delivering a lot of food to the families of young people who he'd normally work with in person. He's seen how the pandemic has made bad situations worse.

"You're going to have a lot of kids that are frustrated, and you're going to have a lot of kids who see their parents' situation and it frustrates them, too," he said. "I think you're going to see a lot of kids acting out. Hopefully they don't, but I think we're going to see a lot of that now."

Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen told Denverite last month that he's also concerned about an uptick in violence related to the pandemic. Through April, illegal gunshots rose to levels the city hasn't seen in years. Aggravated assaults were also up from this time last year. Pazen said the department saw a lot of violence between families in neighbors, but that it wasn't necessarily domestic violence or gang-related, just people who got into arguments that escalated.

Distrust of police plays into this frustration, and it's also been heightened during the pandemic. While Hodge said he has a good relationship with the department, that distrust is the reason his intermediary role exists.

Now that masks are required in the city, he's worried officers may have another reason to stop and search young Black kids like his son.

These same problems, brought to a boil by coronavirus lock downs, played into massive protests in Denver and across the nation.

Fresh off the State Capitol steps after announcing a new bill to increase police accountability and transparency last week, Rep. Leslie Herod said inequality exacerbated by the pandemic played into the recent outrage seen across the nation.

"COVID has highlighted the inequities that currently exist in society, and so does this," she said. "When you find out that global pandemic is disproportionately impacting us and no one's saying anything about it, no one's doing anything about it, you realize how little people care about us, and it's time to fight."

Elisabeth Epps, a justice reform activist who introduced Herod to the crowd on Tuesday, said she didn't think the nationwide protest movement would have emerged if George Floyd had been killed by Minneapolis police when lock downs were just beginning.

Bechhoefer also thought the pandemic contributed to the massive outcries.

"I hate to generalize across an entire population, but for many this is the straw that broke the camels back, the spark that ignited the fire," he said. Lost jobs during the pandemic and the killing of an unarmed Black man have shown him that "our democratic republic has failed in many ways."

While the marches, speeches and shouting in Denver's streets have mostly centered around police brutality, people at the protests invoke broader systemic racism. One sign at a Saturday rally in front of the Capitol read, "Food deserts are racial violence."

On Colorado Matters' June 2 episode, Colorado Council of Churches executive director Adrian Miller said violence has always been a part of the American experience for Black people.

"Black existence in this country has always been tied to violence. My ancestors were brought here forcibly to do uncompensated work," he told host Ryan Warner. "We should never lose sight of the fact that we are protesting rejecting a system that tries to keep us in a certain place in society."

Terrance Roberts is a former member of the Park Hill Bloods who, like Hodge, began working to improve his neighborhood in adulthood. While he's battled gang violence in the city for years, he said this moment brings him hope that people may come together, and the path toward destruction this summer may be reversed.

"These last eight or nine days has really changed the conversation. There's a different consciousness right now," he said. "This is the time to capture that positive energy."

Roberts said he was encouraged to see Crips and Bloods standing in the street together during the marches, though he also called some people out for staying at home. There's a conflict of interest for some gang-affiliated residents, he said. Some work as informants for police, and they may not be ready to go stand in the street against unwarranted brutality.

On Saturday, Roberts, Hodge and McBride were all present at a rally in memory of Elijah McClain, the unarmed 23-year-old who died after interacting with Aurora Police last year. Hodge said shootings in Montbello had continued into the weekend.

"There is white supremacy and systemic racism, and that is why someone chose to pick up a gun last night," Roberts told the crowd.

"The fact that we have young men and women who feel hopeless -- who feel there's nobody who cares -- that they have to become gang members in the land of the so-called free. In the land of the cowards who murder people of color."

He said people need to stand up against everything "that's killing us." Not just police brutality but youth violence and environmental injustice.

Hodge challenged the crowd to help him in his work.

"Worse than the white man killing us, to me, is our own kind killing us first," he said at the microphone. "Show up over there and say 'we've had enough.' Y'all scared to do that one."

The next few months may look bleak, but Hodge is not slowing his efforts to keep people safe.

On a warm evening in May, after Denver's stay-at-home rules were about to lift, Hodge, McBride and other youth violence workers marched through Montbello. They prayed as they walked. Hodge's son, Dini, held a giant banner reading, "We can, we shall, we will stop the violence."

Through his mask, Stephon Cummings spoke to followers watching a Facebook Live video. He's a case manager with the Gang Reduction Initiative of Denver, known as The GRID.

"We want to pray for the community. We want to pray for the individuals affected by all these things. We want to encourage the community to be active, to help one another out, to love on one another, to do whatever they can to support each other," he said. "Because this is the most unprecedented time that I've been a part of. I'm 43 years old, and I've never seen a situation quite like this."

Both Hodge and McBride said their presence on the street sent a strong message to the community.

"Everything you see is confusing," McBride said. "These kind of things are definitely mandatory and necessary to show our kids that we're still here and we still care."

Love is the inspiration for Hodge's work, the namesake of his foundation and the message he preaches as a solution.

"People don't have outlets for their anger. And people don't have love, which is basically the bottom line," he said. "If you don't have an inkling of love in your body, you don't care about nothing. And I know that for a fact, because I did that for years in my life."

In mid-May, the city saw a rash of violence. Denver police responded to four shootings and two stabbings in just a 12-hour span. Days after the violence, Hodge was at home doing yard work, waiting for a lieutenant to call about a family he should visit.

"I can't take no more. Really, I can't. It's too much. I lost all my friends that I grew up with from kindergarten to gun violence," he said.

But the work is too important to him to quit, in part because he's still surrounded by the violence he fights. One of the shootings that week took place close to his home.

"We live here. Our kids play here," he said. "My nieces play on that street, and you think I'm not going to go over there and say something?"

He said he's encouraged that his son and little brothers are learning the ropes to one day take his place. It's a responsibility Griffin said he's ready to carry. Hodge has inspired him.

"He's going to give a lot of people a good outlook on life, and an outlet to know it's OK and to keep going. I respect what he's doing and that's why I'm there every day," Griffin said. "I want to take the loss that I had, but I want to come back who I was and I want to be a role model. Keep fighting. Never give up. Never give up."

For Bechhoefer, initiatives like Hodge's that come from within communities are the most crucial to hold people together. It's why his group funds local organizations and why it's launching a media campaign this year to try to instill kids living in Montbello with a sense of pride about where they live.

While the neighborhood has seen some dramatic changes in recent years, he's seen the community step up to take care of its own.

"There's been a growth in nonprofit organizations and civic engagement in Montbello," he said. "That's been really encouraging."

Roberts also said recognition for community-led efforts is due. A long-time emphasis of news stories on the neighborhood's tragedies misses the fuller picture, he said, and could actually work against the progress people like he and Hodge are making. People, he said, "read the energy of the city and they follow it."

"There's a lot of us doing this when nobody's gotten shot," he said. "We do have some phenomenal activists, and I want to stay positive."

If the protest movement can begin to heal some of the nation's systemic problems, Hodge said he won't always have to do his job.

"It will bring some change, you watch," he said. "Everybody has had enough. It's not just us, our race. Everybody's affected by this un-love that we have in our world."