Last month Joel Hodge, who runs the Struggle of Love Foundation in Montbello, was one of several people from the neighborhood who told us pandemic lockdowns could create a tinderbox that would light the city on fire.

Denver has seen a rash of homicides over the last few weeks. Hodge believes his predictions are, sadly, coming to fruition.

"Months ago, I told everybody. You just have to weigh the facts. Kids don't have to go to court. Kids didn't have to show up to probation. Kids didn't even have to report to nothing. To school. Nothing," he said, pounding his desk with frustration. "So you think of those knucklehead kids. All they're going to do is resort to getting some attention some way. And it's unfortunate that the only way we know how to get attention in our neighborhood and our community is violence."

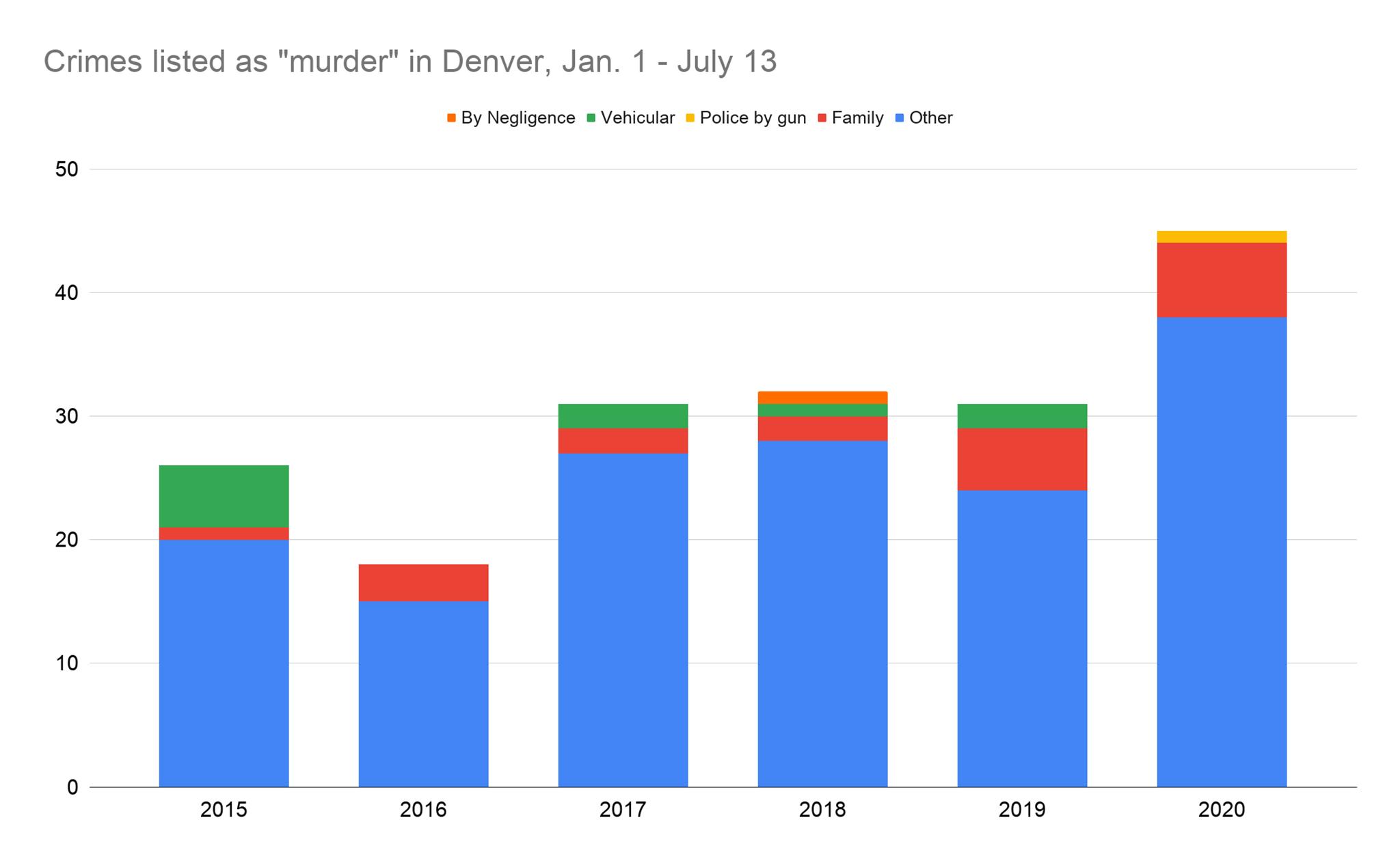

Denver Police Department's public crime data lists 45 instances of "murder" between Jan. 1 and July 13, 2020. It's the highest of any year since 2015. May, June and July account for the top three months of the year -- and, of course, July is only half over.

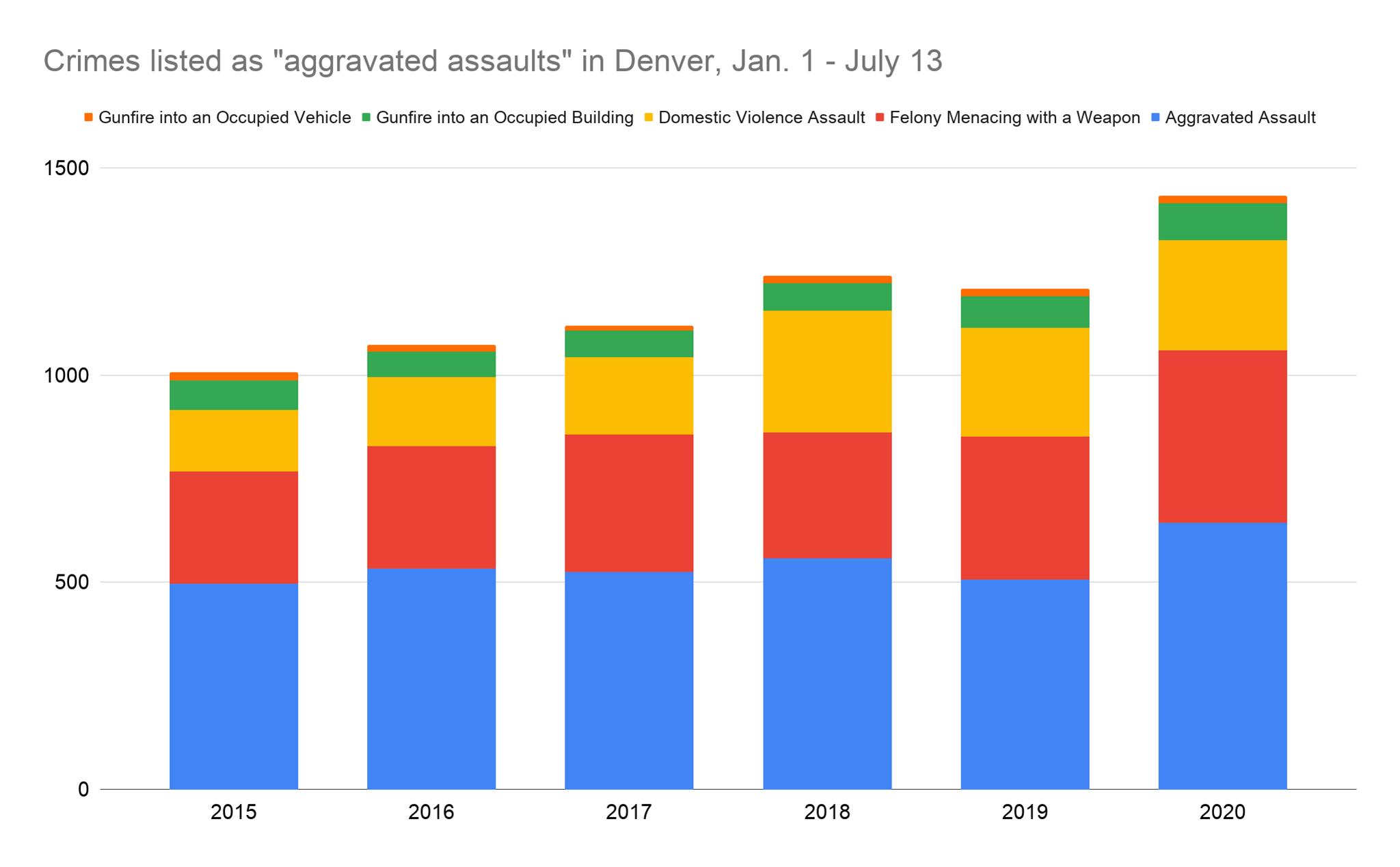

There were also more aggregated assaults between Jan. 1 and July 13, 2020 than any other year since 2015. Only two days in 2020 do not have an assault, according to DPD's data. And three days recorded more than 15 assaults, which all happened in the last month.

There were eight homicides in the first eight days in July. Victims' ages ranged from 14 to 40. Each of them left behind family and friends who now must deal with their absence.

"2020 is going to get studied for years," DPD's Chief Paul Pazen told us. "It's something we haven't seen."

There are two major factors that make this year unlike any other, he said.

First: the pandemic.

Lock downs have added stress and anxiety to people's lives, but Jason McBride, who works with Denver's Gang Rescue and Support Project, told us COVID-19 likely impacts kids from low-income families harder than others. He knows young people whose parents have lost jobs.

"You're going to have a lot of kids that are frustrated, and you're going to have a lot of kids who see their parents' situation and it frustrates them, too," he said.

The pandemic has exacerbated systematic problems that have long disenfranchised poor people and people of color. It's created desperation that's manifested into rage.

Pazen also pointed to COVID-19 precautions as a problem. Denver has purged its jails to keep the virus from spreading inside them. People who might otherwise be locked up are now out in the city. Pazen said 30 percent of homicide suspects under investigation this year would have been in jail or interacting with another part of the justice system in normal times.

"Had these individuals been in custody, would that homicide had occurred?" he said.

When he spoke to us a few months ago, McBride compared the situation to students in class with a substitute teacher. They know they can get away with more.

Another major factor contributing to violence, Pazen said, is the city's current "civic unrest."

The way Pazen described it, violent crime can only be dealt with through collaboration between communities and police. Cops do things like take guns off the street, he said, adding DPD has collected more than 850 firearms this year alone.

Community members watch over each other, he said. Hodge, for instance, has spent the better part of two decades working to quell violence in Montbello. He can reach people who don't trust police, and Pazen's officers work with him to keep bad situations from getting worse.

But recent uprisings against police brutality, Pazen said, have shattered this kind of partnership.

"It's hard to say in recent memory (when) our communities have been more divided than they are today," he said.