Kim Engler had a great tube through Littleton's South Platte Park in late June. Eager to give it another go, she scouted out the river just downstream of the Chatfield Dam before heading out with some friends on July 18. The South Platte River seemed to have more water than it did on July 4, but the flow was still noticeably weaker than before.

"From the 28th to now is completely different," she said as she inflated a tube, determined to forge ahead. "We're just going to go for it."

Visitors to South Platte Park are greeted these days with signs with skulls and crossbones reading: "TUBERS BEWARE!! LOW RIVER." An automated phone message from Adventure West River Tube Rental, which runs some operations at Reynolds Landing by the Breckenridge Brewery on Santa Fe Drive, said its Littleton location is closed "indefinitely" due to low water levels.

That's bad news for folks like Engler, who loves the mostly slow float through ecosystems teeming with wildlife.

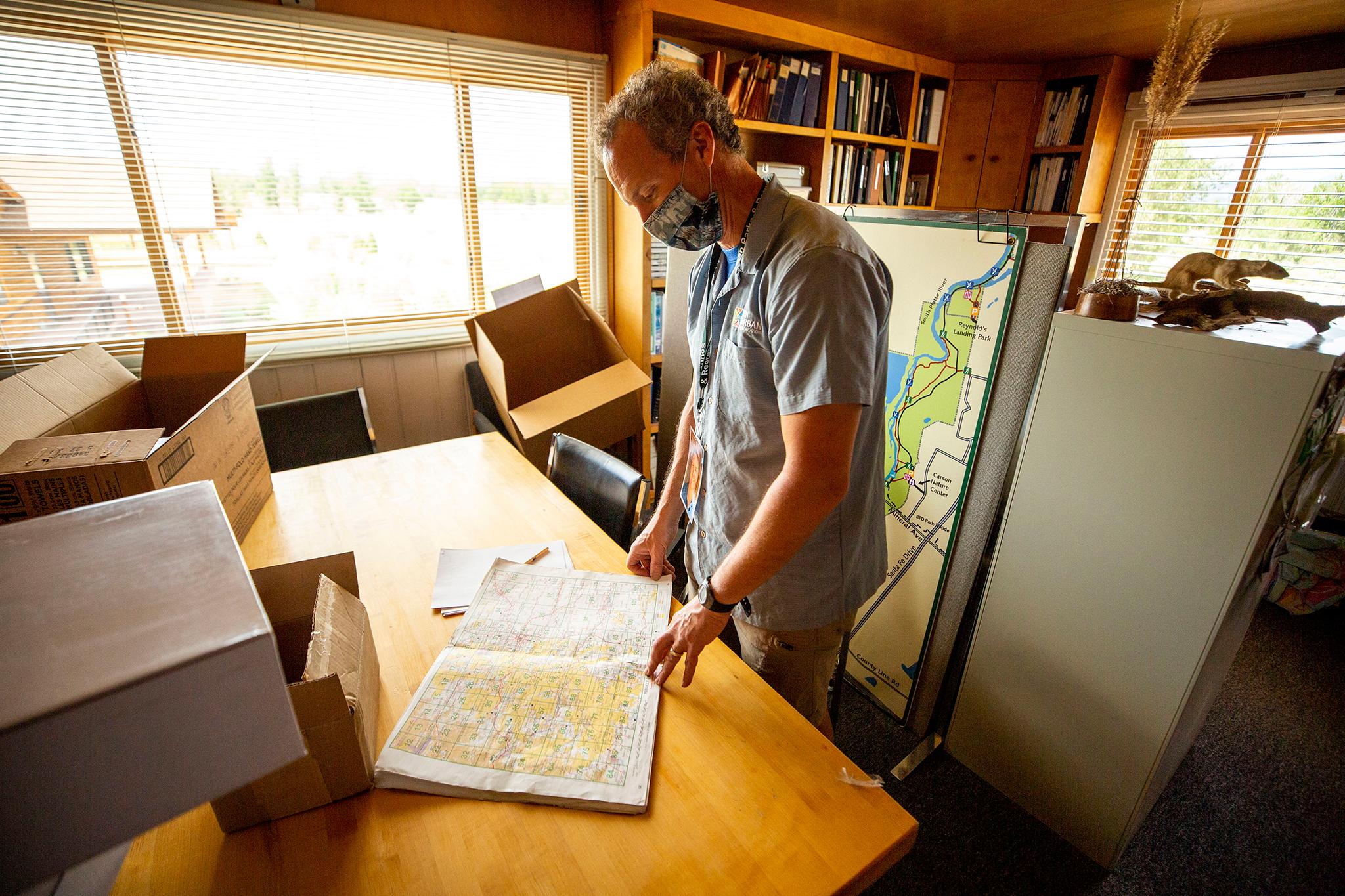

Skot Latona, the South Platte Park's manager, usually recommends tubing only when the local stream gauge registers at least 100 cubic feet per second. People who try to float now risk damaging the ecosystem and sinking their tubes.

"It is kind of a miserable experience," Latona said. "They're probably walking hundreds of yards at a time. If they have a cooler, they're having to carry that, drag the kids. Any dragging and tubes get popped."

Park rangers plan to display about 30 deflated floaties in a kind of tube graveyard.

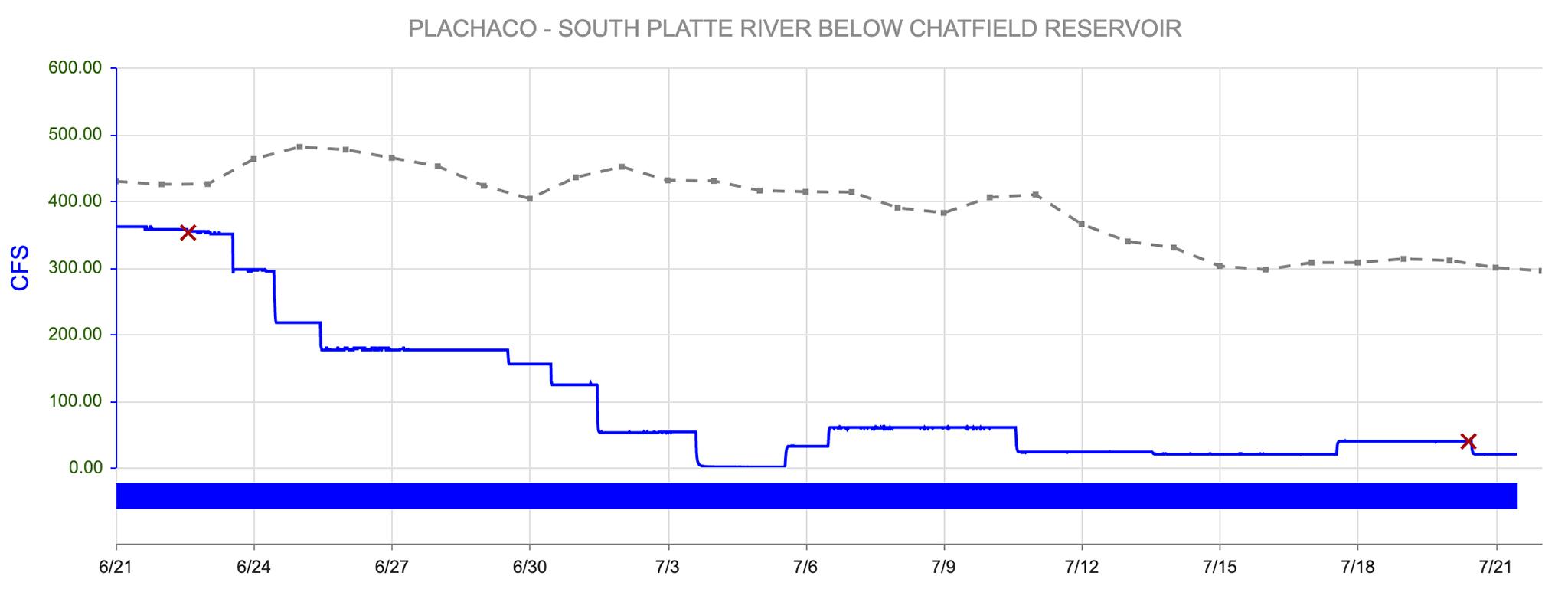

Conditions were ideal for about two weeks, but the flow plummeted on July 1. Two days later, virtually no water was coming through the dam.

The reasons why, Latona said, have to do with snowpack and the need to keep local faucets running.

While Colorado's snowpack was looking very good this winter, about 120 percent of the average, he said the expected runoff slumped to about 60 percent of normal levels. It's been a hot summer, and a lot of that melting water simply evaporated or sunk into the dry dirt before making its way into river systems.

Thirsty cities that rely on water from the South Platte have had to juggle their supplies to make sure customers get the service they expect. Denver Water's intakes are upstream from Chatfield Reservoir, so the water it draws from the South Platte has no reason to travel through Littleton's excellent tubing areas. There's no excess in a dry year like this one, so hardly anything will flow from Chatfield's dam.

On average over the last 30 years, between 300 and 500 cubic feet per second has flowed through South Platte Park in July. Latona said he's seen a change in the last decade.

"I do think we have a new normal of the last 10 years," he said. "The new normal comes from continued expansion of the metro area and more water storage capacity and water consumption, plus 'creative' ways of moving water through city systems rather than the river."

These "creative ways" refer to super-complex exchanges of rights that owners can use to pull water from other systems.

Brent Schantz, who manages flows from the Chatfield Dam, said managers who own water in the reservoir will try to exchange every drop of their rights in dry years to make sure they have supplies available further upstream.

Denver Water, for instance, draws its supply in the system from the Strontia Springs and Cheesman reservoirs. A majority of the metro area's drinking water is piped in from the Western Slope, but the droplets Denver Water does get from the South Platte need to be preserved in these pools upstream from Chatfield. Denver Water told us it releases water from its reservoirs on the other side of the city to deliver supply to folks downstream. By releasing it there, bypassing the stretch of river between Chatfield and Confluence Park, it can store more water upstream for the city's drinkers.

In dry years, Schantz said, you can either have water to drink or water to tube.

He added that the 30-year average water levels for a place like South Platte Park can be misleading. The region has had a lot of good years.

"It makes a dry year look so much worse than it is," he said. "This happens. We live in a desert."

But the idea that a warming climate could increase the frequency of those dry years is something he said is always on his mind.

"It concerns to me to no end," he said.

He's less worried about tubers than he is about the various farmers, municipalities and states that all have claims to the river.

Latona said the region's growth also plays into concerns about supply. Things were really good when the metro was growing quickly, and he expects newer residents have no sense of what it means to live in a serious drought.

"We have had such a wet season during our biggest growth," he said. "I think there is concern our growth will exceed our water at some point."