On Friday, City Park Golf Course finally re-opened. The municipal grounds closed in 2017, with some resistance from residents and at least one funeral for doomed trees, to make way for a renovation that was meant to create new floodwater infrastructure in the heart of the city.

Flooding is a historic problem in Denver. Though it's dry here most of the time, waterways like the Cherry Creek frequently flowed over in the city's early days after sudden and heavy rains. Projects like the Cherry Creek Dam helped deal with the most regular surges, but parts of town are still unprepared for the worst events today.

Sam Stevens, an engineer with Denver's Department of Transportation & Infrastructure, said the stormwater systems between City Park and the South Platte River are not built for a 100-year flood event, the kind of big storm that is statistically supposed to happen every 100 years. But don't let the name fool you: It doesn't mean these storms actually happen once a century. Back in 2007, Colorado's state climatologist said it's not uncommon for such events to occur more than 100 times a year across the state.

The bottom line: Parts of Denver are not built to handle the biggest rainstorms, and the city has worked to deal with that vulnerability.

For the neighborhoods Stevens mentioned, the new golf course's infrastructure should help keep them afloat during very wet times. It also features a new trash vault that will help keep garbage out of the South Platte. There's a lot more happening there than sand traps and bogeys.

Here's how it works.

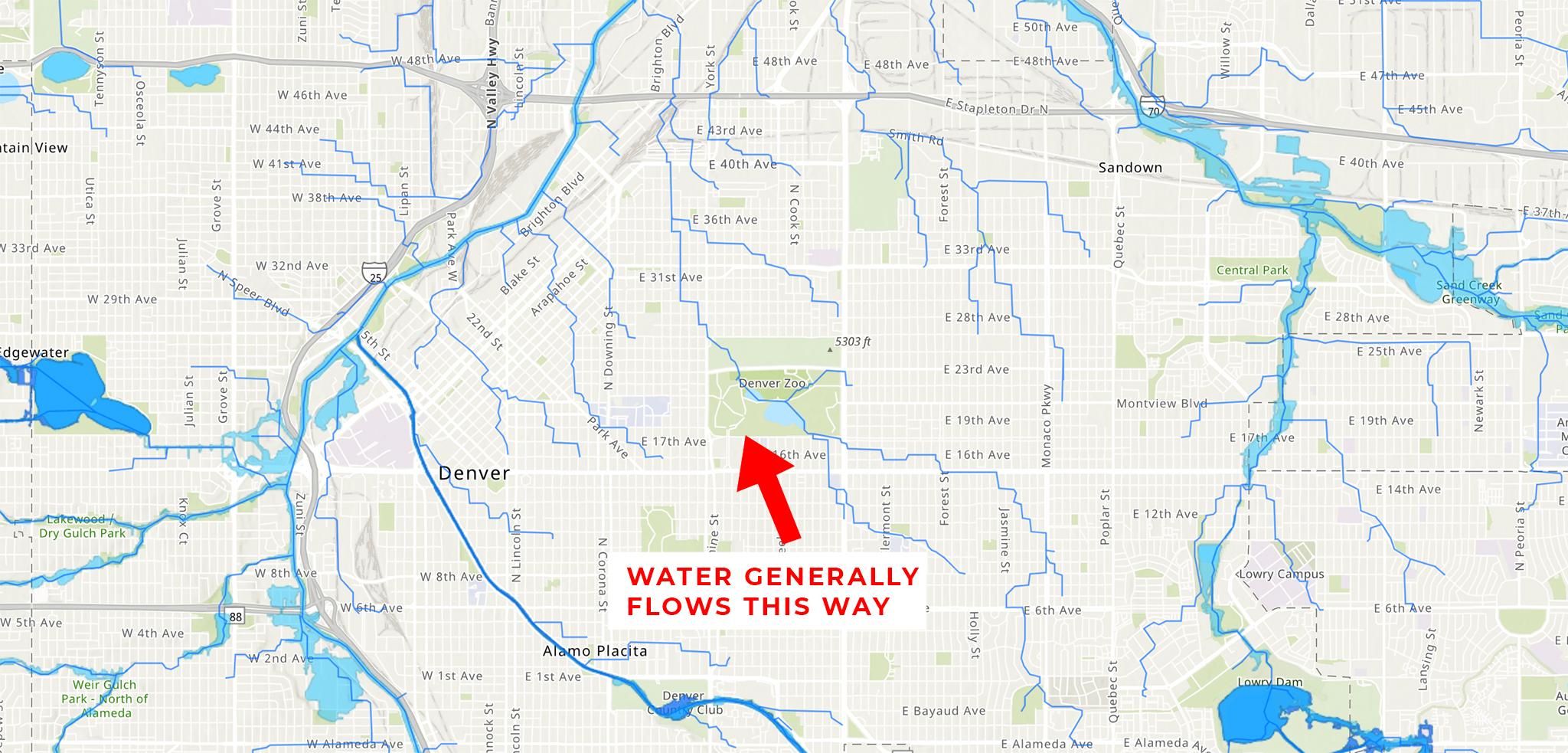

A lot of stormwater channels run beneath the city. The water around town generally flows toward the South Platte; channels leading beneath City Park flow north and west until water meets the river. These pipes begin as far southeast as Alameda Avenue's intersection with Quebec Street.

If there's a huge deluge that fills these pathways, any water upstream from City Park will end up in a detention pond at the golf course. For most events, it'll just fill up the pond and not bother golfers too much. But the system is set up to handle every drop of a 100-year event, about 67 million gallons.

The worst storms will make the course unusable for about 24 hours after the rain stops -- not like anyone wants to swing a club in a downpour, anyway. Water from the pond will flood the surrounding fairways and can even cover cart bridges in that low area.

"It does fill up pretty quick," Stevens said.

The system is set up to slowly release that water back into the storm drain system, which will stop it from overwhelming the older, less robust channels in places like Cole and Elyria-Swansea on its way to the river. Stevens added the golf course improvements should help the city avoid upgrading stormwater drains past the golf course to accommodate 100-year floods: "That would be a lot more expensive than what we did here."

Scott Rethlake, Denver's director of golf, said the system has been tested a few times since it began operating about a year and a half ago. Storms have already filled the basin up to the bridges, and he said he's happy things appear to be working as they should.

Bigger storms could still cause problems, and they're not unheard of. The downpour that caused huge flooding in Boulder and up Big Thompson Canyon in 2013 was a 1,000-year rain event.

How will City Park Golf Course work in a storm like that?

"We're all running to the mountains for a 1,000-year flood," Rethlake said.

Stevens mentioned most stormwater infrastructure is built for 100-year events.

While some scientists say more intense rainstorms may result from climate change, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study from 2015 predicted global warming may decrease the frequency of these events in the Front Range.

The golf course will also help clean the river.

The city does a lot of work to keep pollution out of its natural waterways. It's one big reason why people get ticketed when they don't move cars for street sweepers. It's also why "green infrastructure" projects have popped up along redeveloped streets like Brighton Boulevard; you may have seen the impoundments along sidewalks there. There was a time when Denver would let anything flow down a drain and into the South Platte, but no longer.

One feature of City Park Golf's new detention pond is what Stevens called a "trash vault." Garbage that floats into the stormwater system upstream from the course gets trapped in a concrete basin beneath the fairway and is regularly hauled out by city crews. Stevens said he's seen what's down there.

"The amount of trash we've been pulling out of here is just unreal," he said. "When you pop it open, it's just full of cigarette butts. It's pretty nasty."

Cigarette butts, by the way, are the river's single biggest pollution problem, according to Greenway Foundation executive director Jeff Shoemaker.

Oh yeah, and you can golf, too.

The new course is a "18-hole Par 70 with returning 9s" and a driving range.

If you're looking for a review of the holes, or someone who knows what "returning 9's" means, I am not your guy. You might just have to play it to find out, although I can say: It does look pretty nice out there, wildfire haze over the looming skyline notwithstanding.

The only trouble you might have is booking a tee time. Rethlake said the first three days were booked up in just ten minutes.