Hailey Bauer has long loved a good fight.

She grew up outside of Lincoln, Ne., where she was introduced to the art of fencing during summer camp when she was a kid. Bauer, who prefers individual sports over team games, was hooked.

"It's like a game of chess," she said, a contest of strategy that plays out in milliseconds.

But the challenge, and the fun, can fade without new opponents. And there aren't a whole lot of people who fence from a wheelchair, like she does.

Bauer was the first athlete in a small cohort of adaptive fencers that have found a home at the Denver Fencing Center, a huge gym in Ruby Hill that mostly caters to able-bodied sword wielders. The club's founder, Nathan Anderson, hopes to change that by growing his wheelchair program into a national hub for athletes like Bauer. His dream, he said, is to take an entire team to the 2024 Paralympic Games in Paris. This summer, he clinched a $20,000 grant from USA Fencing and the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee to help move the club toward this goal.

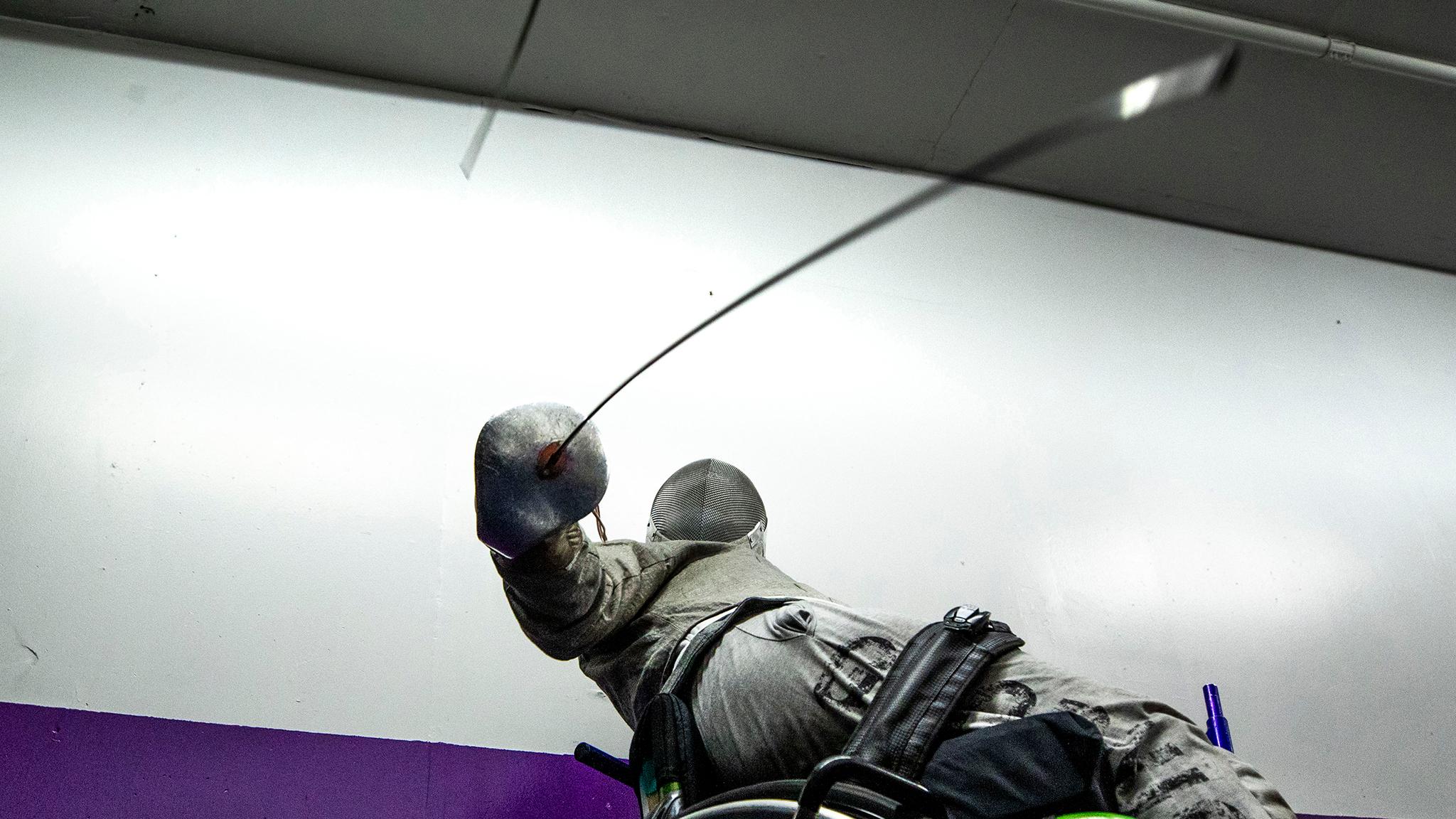

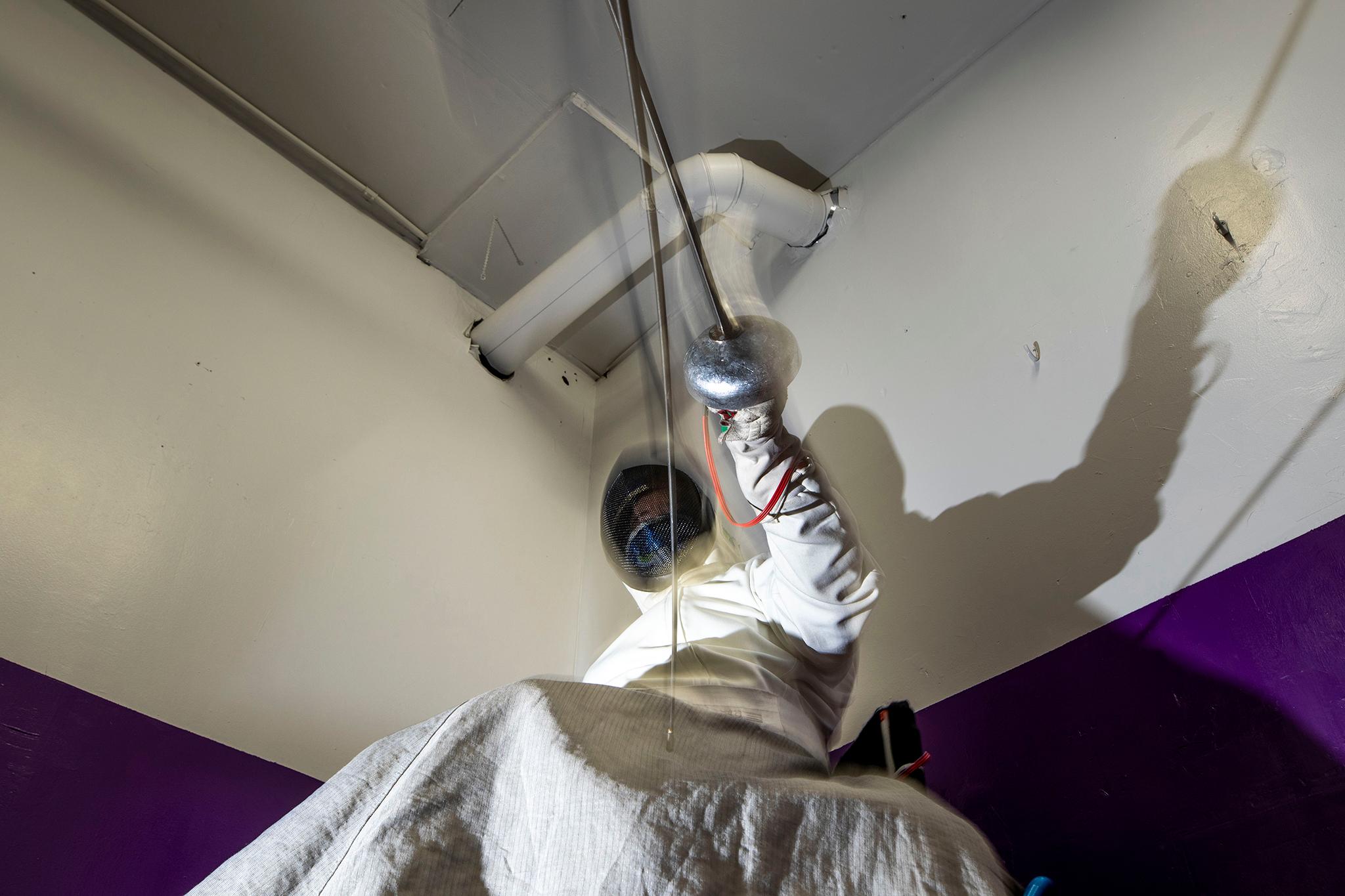

Parafencing condenses all of the sport's thrusts and parries into a fixed stage.

According to the International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation's rules, people with impaired muscle power, range-of-motion issues, nerve disorders and more can compete in the sport.

Bauer, for example, does not rely on a wheelchair to get around all the time, but the cerebral palsy she was diagnosed with as a baby means her muscles can quickly tire to the point that she has trouble walking.

The wheelchairs she and others use to fence are anchored to rigs that pit contenders against each other at close range. Athletes cannot back away from their opponents, like fencers dancing back and forth on a strip. To land points, sword work must be precise and lightning-fast. Rounds are often over in seconds.

All of this gear is expensive, as is travel to tournaments where Bauer and others can qualify for larger competitions. Anderson has already used some of his grant money to buy a second setup for the adaptive athletes. The rest will cover travel - once tournaments begin again after cancellations due to the pandemic - and marketing to attract new talent to his gym.

While tournaments and winning are certainly on Bauer's mind, she's most excited at the prospect of new competition at home.

Bauer was fencing in a tournament back in Nebraska when she met Anderson. She was hungry to grow as an athlete, but there weren't a lot of opportunities to pursue her sport where she grew up. That day, she said, Anderson asked if she'd consider picking up her life and moving to Denver to join his gym.

"If the biggest problem is fencing [new] people, we can do this thing," Anderson recalled telling her. "I've got this club. I've got all these people."

She was 18 at the time, and she was already thinking of leaving home to pursue an education in medicine. Bauer said she went home and talked to her mom about the prospect. She was excited. But it was also a big leap.

She was committed to her training and, before long, she and her mom packed up her things and headed west. Bauer became the Denver Fencing Center's first Paralympic pupil.

Though there weren't other fencers like her when she arrived, the club's coaches began to re-learn the sport from seated positions to help her grow. Bauer trained hard, devoting nearly every waking minute to her craft. In 2019, she traveled to São Paulo, Brazil, to compete for a ranking that could land her on an international team.

She wants to keep pursuing the sport's upper echelons, and she hopes the grant money will help build a community where she can be challenged every day.

"There's power in numbers," she said. "If we can get more people out here ... there's a chance for even further funding, even more chance to get more people on that national level, more people on the international level."

Parafencing is fairly small in the United States, she said, and the women's division is even smaller. She'd like to see the sport grow, so it might thrive nationally while it feeds her competitive spirit locally. And, she added, there are few things better than a worthy opponent.

Anderson, who's long been ingrained in the fencing world, sees the program as a way to expand the sport as a whole.

"I've always looked at different avenues where we haven't had representation and inclusion. I think para-fencing is one of the places that we can really advance," he said.

It's one reason he invited Bauer to Denver. The money, he added, "is like adding fuel to the fire."

A bigger program could do more than stoke competition.

The wheelchair program in Ruby Hill is still small. During training hours, three days a week, it's usually just Bauer, Rachel Malone and Terre Engdahl training amid the cacophony of clanging swords.

Malone and Engdahl are hungry for the program to grow, too, though for different reasons than gold medals.

Engdahl was able-bodied until a car crash five years ago, when he was 21. The incident led to a traumatic brain injury and then a stroke, which resulted in cognitive troubles that disrupted his speech and attention. He's recovered a lot since the day he left Craig Hospital in a wheelchair - he can now get around on two feet - but he still has trouble expressing himself.

When asked if he's excited that more para-fencers might join his ranks, he nodded, eyes bright: "Excited! Exciting."

There is a lot of unarticulated meaning in those words. Engdahl knows what he wants to say, but making it come out of his mouth is difficult. He does not struggle to maneuver a sword with precision, however.

His mom, Susan, said he fell in love with the sport about a year ago when the Denver Fencing Center opened for graduates of Craig Hospital's recovery program. He began weekly para-fencing training at the gym soon after.

"He would live here if he could," she said. "The more people involved, the happier he will be."

Malone was born with paralysis below her waist and has used a wheelchair her entire life. Fencing is not her first adaptive sport. She's competed, and won accolades, in curling and shooting. She's skied since fourth grade.

But the Ruby Hill fencing gym provides a place where she can compete all year long and pursue a new skill set without much trouble. She doesn't need a lot of help to participate. Skiing, for example, requires "a whole team" to get her on a ski lift and keep her safe on a mountain.

Malone said funding adaptive sports is important beyond providing a place to compete. The fencing gym could become a place where differently-abled people can find each other.

Kids who rely on wheelchairs sometimes "internalize" stress that they see in their parents, she said, who often struggle to balance finances and time to navigate a world that's often not designed with their children's needs in mind. A gathering place like the gym could help families lean on each other.

Malone was the only person in her small-town high school that used a wheelchair, she said. Often, she alone held the burden of figuring out how to get by.

"Everything I found growing up was me looking for it, and it was really stressful," she said. "I know how hard that is."

Susan Engdahl said her family faced this reality overnight when Terre left the hospital.

"It became painfully obvious, right away, the lack of access," she said.

A place that caters to her son's needs and gives him space to express himself, she said, means a great deal to them. She expects it will mean a lot to other families who find this place, too.

"You want them to participate and interact with society and enjoy themselves and get something physical out of it," she said. "How do you even put that into words? I can't quantify that. I cannot."