A project that’s been in the works for years has finally, officially, opened.

The 39th Avenue Greenway is a flood-control mechanism and park that stretches between Franklin and Steele streets through the Cole and Clayton neighborhoods. It cost almost $90.8 million, paid in large part by annual stormwater fee collections.

It’s one in a suite of projects referred to as the Platte to Park Hill stormwater plan that’s meant to reduce flooding in the area. The recently revamped City Park Golf Course, improvements to Globeville Landing Park and new infrastructure at the Park Hill Golf Course also play into this effort. Basically, this part of the city was built with small pipes and few places for water to go during big storm events. These projects situate recreation spaces on top of new routes for rainwater to get to the South Platte River without collecting on roadways.

What used to be a very industrial area now invites residents to walk and roll past swanky playgrounds, over stylish bridges and to swinging benches hanging under modernist awnings. The people we met there were pretty happy with how it turned out.

Still, the greenway was the subject of some controversy as it was developed. Now that it’s been completed, here’s a recap of the conversations Denver had about this project along the way.

If you don’t know, now you know: Stormwater can be controversial.

When the city began planning the greenway project back in 2016, there was already growing resistance to the entire Platte to Park Hill plan. Some neighbors called it a “boondoggle” and accused the city of ginning up the projects because they helped protect the also-controversial I-70 renovation plan that the Colorado Department of Transportation had begun.

It was such a familiar talking point that the FAQ section on the greenway project’s website addresses it directly: “Is this project being pursued due to I-70 reconstruction? No.”

Nancy Kuhn, spokesperson for Denver’s Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, told us this part of the city needed flood improvements regardless of what happened with the highway. It’s the largest flood basin in town without a natural exit ramp for excess rains. Still, she said there were benefits to hitching it to I-70s renovation and that CDOT’s flood planning work did benefit when the city put Platte to Park Hill in motion.

“Yes, I-70 benefits, but so do 485 at-risk structures north of 39th Avenue,” she said.

“We were lucky with the timing,” Sam Stevens, a DOTI engineer, added. “We were lucky to be able to leverage them for funding.”

Like similar features at City Park Golf Course, the greenway will allow heavy rainfall to drain into open-air channels and then toward the South Platte River. DOTI has also installed two trash collectors along the greenway, which will help remove litter (mostly cigarette butts) from the flows. The department installed a system like it at the golf course, too. For the basin to go from zero litter filters to three in a year, Stevens said, isn’t nothing.

The greenway has seen some decent rainfall already this year. So far, Stevens said, it’s performing as expected.

It’s also worth noting that there were some environmental concerns as the bulldozers got to work along the greenway. Residences — but not industrial areas — all around the area were part of a huge Superfund site until recently. Some neighbors feared digging so deep into the soil would kick up historic pollution that could float into their bodies.

When we looked into these questions in 2018, it was clear that there was plenty of pollution where the greenway now sits. Some of it might have come from burning trash, which used to be a legal way to deal with refuse in the city. Other trouble spots may have been related to historic gas leaks and buried fuel tanks.

“If there was anything there, we had to test for it, and we remediated it,” Kuhn said, echoing what city officials told us back then.

Big projects like this tend to force cities to deal with historic pollution that otherwise would have remained underground and unaddressed.

“If anything, it’s probably better than ever,” she said.

Big projects in Denver usually come with conversations about gentrification, too.

Suzanna Pierrepont was delighted when the greenway was finally unveiled. She bought a home nearby about two years ago, specifically because she knew the project was in the works. She’s been monitoring its progress like late-breaking election results.

“I’ve been checking online pretty regularly,” she said. “It’s so cool. They’ve done such a good job.”

Now that the park is open, she’s got a place to regularly walk Ranger, her dog. That’s where we met her on a blustery Saturday afternoon. Some developments are still under construction nearby, but she said the neighborhood is really starting to blossom into its potential. The 38th and Blake RTD station is very close, and she’s also a quick jaunt to RiNo’s bar scene.

“This whole area is fantastic,” she said.

Julian and Danielle Scott were also out for a walk in the weekend’s high winds. Like Pierrepont, the couple recently bought a place with the greenway in mind, just off the project’s western edge in Cole.

“This is one part of the reason we purchased our lot,” Julian said. “We’ve been waiting.”

Waiting for the new amenity to open, yes, but also for years of construction to finally abate.

“The whole neighborhood is unfortunately accustomed to construction,” Danielle said. For some, it’s worth the wait, but she said she’s not so sure how Cole’s longtime residents feel about all of these changes.

Jamarian Evans-Daniels lives in Globeville with her kids, but she grew up nearby. She took Jaia and Devaughn to the greenway Saturday to take in a new mural of the late Congressman John Lewis by Thomas “Detour” Evans, which was behind a fence until recently.

She thought the greenway project turned out “really cool.” She’d like to come back and hang out when the weather is a little nicer. But she said the improvements have come at a cost beyond taxpayer dollars.

“This is what we always wanted,” she said. “It’s kind of sad that it had to take the whole gentrification thing.”

Big public investments are one part of the recipe for a neighborhood’s gentrification and the possible displacement of longtime residents. In a survey conducted in 2015, both Cole and Clayton were listed as “vulnerable” to these forces.

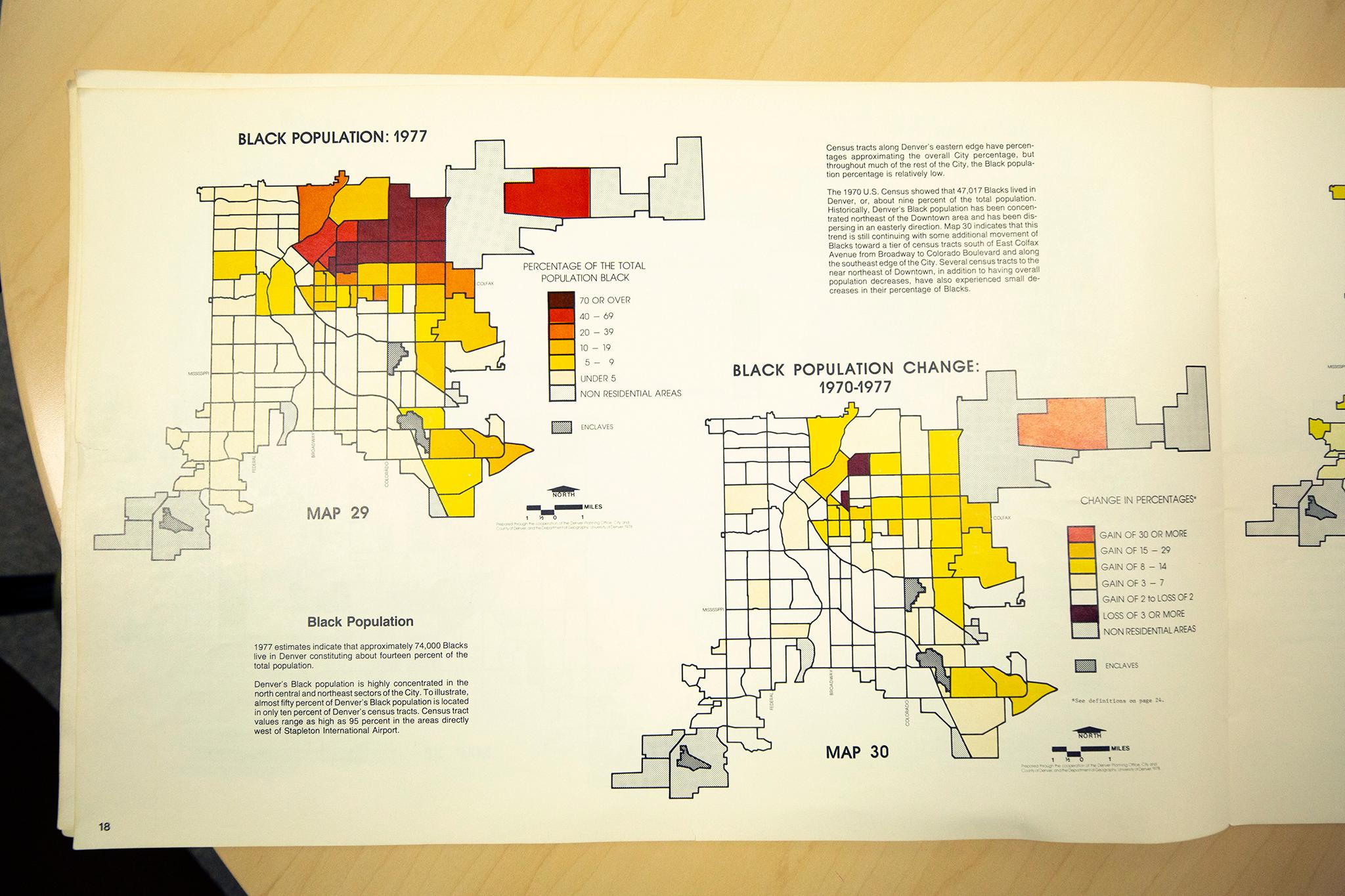

A survey back in the 1970s showed demographics had already begun to change 50 years ago. Cole, in particular, was listed in the “Denver Atlas” as one of two neighborhoods that lost the greatest percentage of Black residents between 1970 and 1977. Still, between 40 and 69 percent of Cole’s residents were Black in 1977. More recent figures show that group shrunk to 16 percent of the population by 2016.

A single greenway project can’t be held responsible for these broader changes in the city, but it might be a sign of the times. Neighborhood improvements, rising property values and displacement have been part of Denver’s story for years. New homes that have sprung up around the project might factor into why a recent study found that Denver ranked second for gentrification trends among U.S. cities in recent years.

Seen in the city's planning offi

This story initially included the wrong price tag for the greenway project. That figure has been updated, and we regret the error.