The staff at History Colorado, keepers of the state's historic collections, were already planning for an important 2020.

It was late winter, and they were preparing to capture Coloradans' thoughts, feelings and objects from an upcoming and consequential election. They began to hear rumblings that COVID-19 was becoming a problem overseas. Then, in March, it became clear they needed to change gears, and quickly.

"Friday the 13th, we all got sent home," History Colorado's chief creative officer, Jason Hanson, said. "By March 25th, we had stood up the COVID collecting project."

He and his colleagues worked feverishly to document how people were feeling about this new reality. They opened a hotline where residents could call in and leave voice messages. They asked teachers and students to send in videos and photos. Over the past few years, they'd begun to cultivate relationships with communities across the state; this year they leaned on those connections, making sure people most affected by the pandemic had an opportunity to be represented in the historic record.

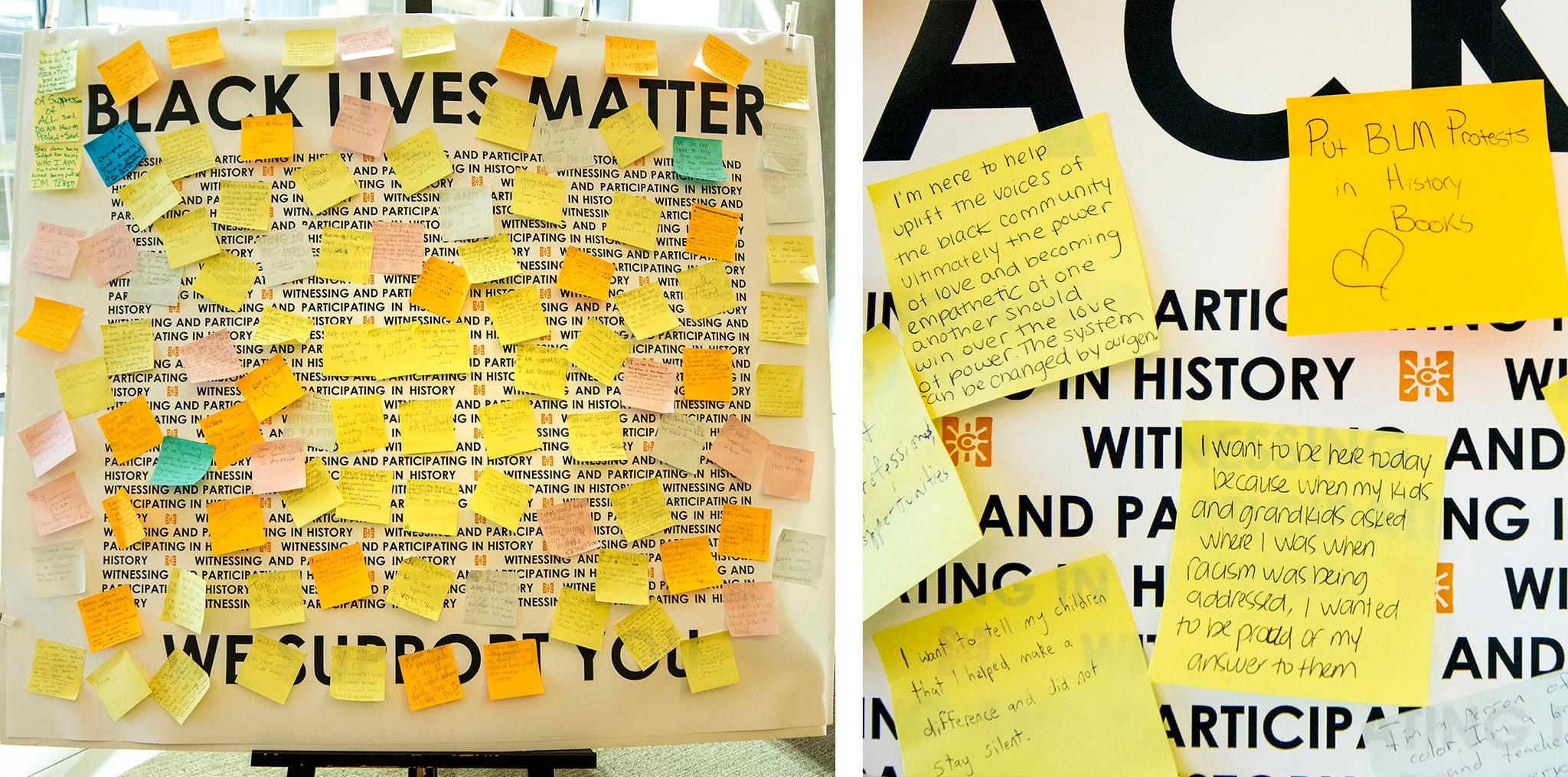

Then, just a few months later, things changed again. The protest movement against racism and police brutality took hold at the State Capitol, just a few blocks away from their headquarters, on Broadway. It was another crucial moment they needed to record immediately.

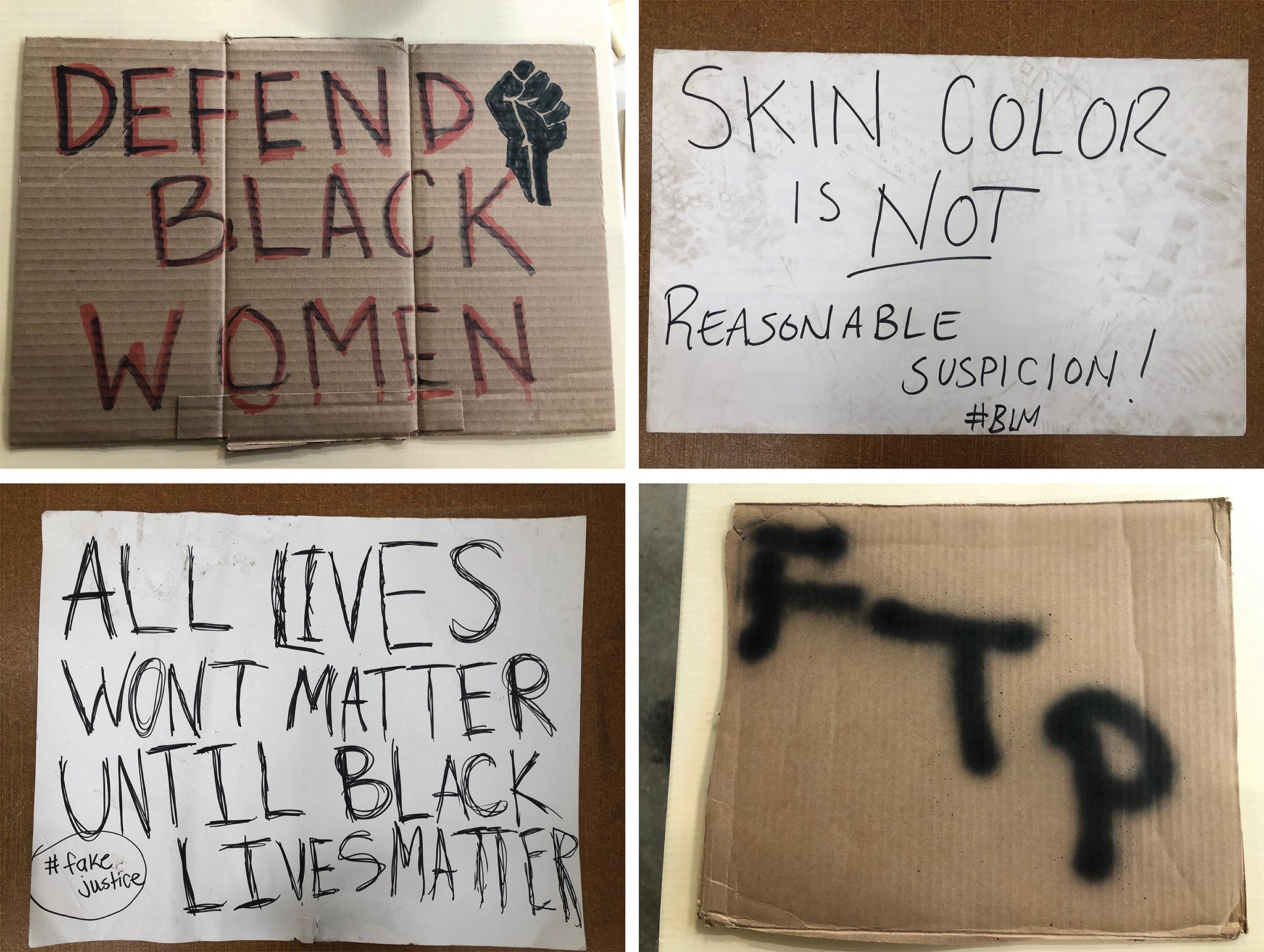

This time, they had infrastructure in place to document the moment as it was unfolding. History Colorado dispatched a battalion of archivists and photographers to record the uprising. They set up collection stations outside, asking people to write their feelings onto sticky notes. Hanson and his colleagues wandered through the crowds, picking up objects discarded in the moment and asking protesters to donate signs and other items once things settled down.

"We were able to adapt the tools we had developed for that COVID collecting program, which was really an idea of crowdsourcing the collection," Hanson said.

These efforts represent a fundamental shift in the ways history is saved for the future. Traditionally, archives like History Colorado and Denver Public Library's Western History Center gather items from lone individuals who built their own collections over time. But in recent years, these institutions have started to assess how the old ways often skewed representations of history. Marginalized communities were regularly left out of the story. The perspectives of white, powerful men were often all that were saved to help historians and the public understand experiences of the past.

In a year of two major crises defined by inequity, the stewards of our collective history knew they had to take a new approach.

When the pandemic took hold of Colorado, History Colorado's staff came face to face with the institution's past mistakes.

"We all looked at the 1918 flu pandemic, and our historians on staff were frustrated," Hanson said.

They had statistics, newspaper articles and a few interviews conducted decades after the fact, but the reality of life in 1918 was largely unaccounted for.

"Unless you had access to a printing press or a microphone, your story didn't get recorded," he said. "We just couldn't get a good sense of the texture of everyday life for people."

Marissa Volpe is History Colorado's head of equity and engagement. In her three years at the archive, she's been working to establish inroads with residents for just a moment such as this.

"Where are those stories of underrepresented and underserved communities?" she said of 1918. "How have we been in relationship with community, so that at the point of something like a pandemic, issues of social unrest, we are in relationship with community so they can tell those stories?"

After lockdown orders came, Volpe got to work. She began with a group of Latinos living in the Roaring Fork Valley, home to many working-class migrants who prop up luxury ski towns like Aspen. History Colorado partnered with La Tricolor, a radio station serving Spanish-speakers in the area, to generate 15 oral histories for the archive.

In the past, Hanson said, institutions like History Colorado would wait as long as 30 years to assess a moment in history and then go looking for materials and witnesses. This way of doing business, which usually relied on singular donations and perspectives, often resulted in "blind spots" like those his colleagues discovered in the record of the Spanish Flu.

Volpe's approach to the Roaring Fork Valley produced something different: a collection of experiences gathered as a group.

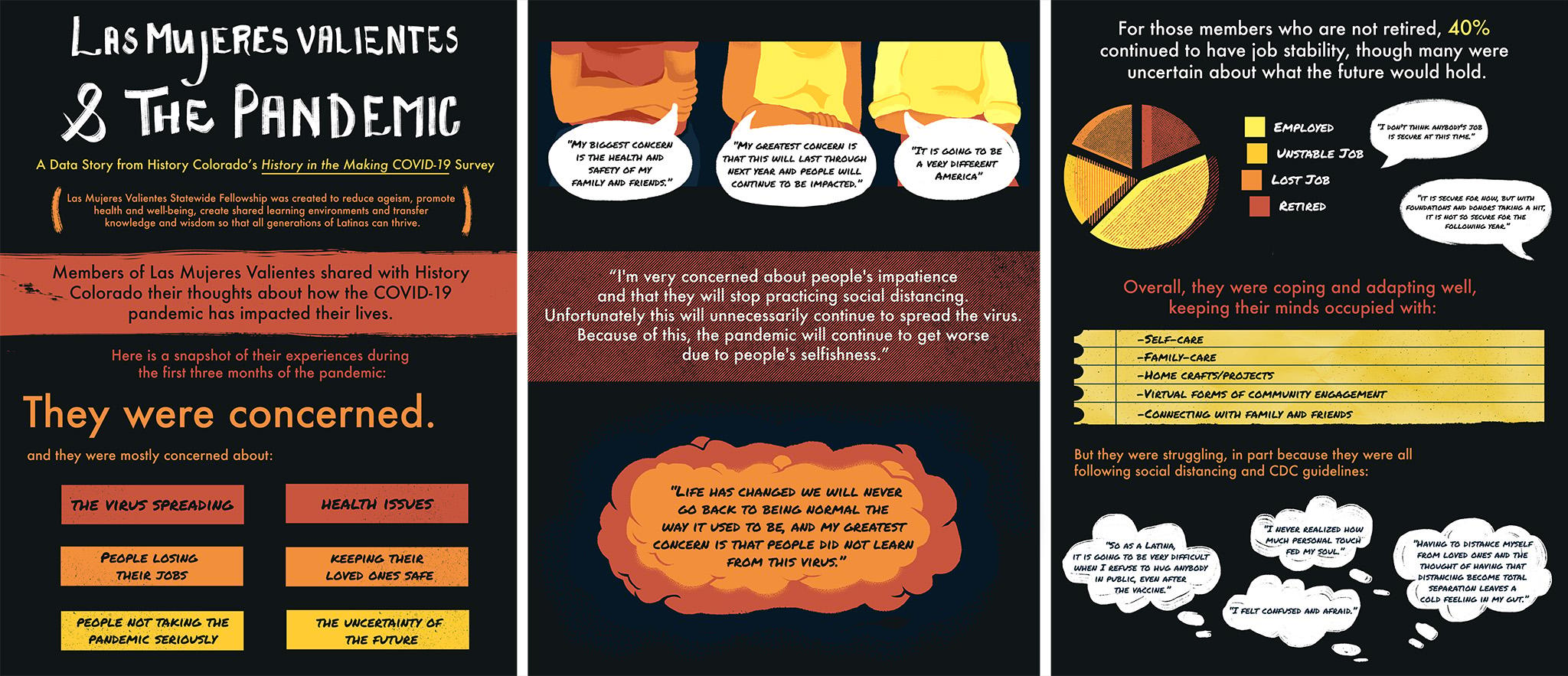

She also worked with Las Mujeres Valientes, a group in Denver that supports older Latinas in Colorado. History Colorado generated a report from the effort. It found that only 40 percent members felt they had stable jobs after the pandemic began. It also highlighted the emotional impact of COVID-19.

"I am concerned that the disparity in our communities of color will continue to grow," one person said.

"Life has changed. We will never go back to being normal, the way it used to be," said another.

But it was important to Volpe that the material did not simply languish in the state archive. Giving back is part of maintaining a strong relationship with communities. History Colorado created that report, in part, to return it to the women who helped create it, so they could use it to apply for grants and change the situations they described.

"We've been able to meet the needs of community," Volpe said. "It's not this extractive process of, let's just take and pirate. But really, we're thinking about the needs of the community and how can there be that reciprocity, so that we're working with and together."

Vople and her colleagues are now pursuing a similar project in Denver. They're working with Centro Humanitario, a day labor center in Five Points, to keep the oral histories coming.

She's thrilled, she said, to rethink what a state archive means. It's an exercise that also played out during the summer of protests, when the collections effort also was an opportunity to ask people what they wanted from the institution.

"We're really at an exciting place," she said. "Like, what is the role of a history museum during this time?"

Denver Public Library is also working in ways it never has before.

Before 2020, Jamie Seemiller spent much of her time keeping up with scores of collections offered to the Western History Collection. As the head of acquisitions, it's her job to meet with people who say they have something worth keeping, to comb through the boxes of documents and ephemera and make sure each submission gets a proper evaluation. But library acquisitions slowed down this year.

"Usually we bring a little over 100 collections a year," she said. "This year we brought in, so far, about 38."

Seemiller said this is both "a blessing and a curse." While it's a departure from the norm, the extra free time has given her and her colleagues breathing room to reassess the city's massive archive. It's allowed her to think about ways to be more proactive, rather than reactive, in her job to preserve the present for the future.

"We're thinking about history differently than we used to. Archives used to be keepers of the past," she said. "Now, we're trying to reshape the past, tell stories that have not been told. And that makes you think, what stories are happening right now that, if not told, will be lost?"

In reshaping history, Seemiller said her colleagues are using this time, while the library is closed, to reassess items that are already part of the archive. They're reworking "racist descriptions" written in past eras and attempting to highlight what diverse perspectives do exist in the collection.

Like History Colorado, they're also trying out new ways to document current events so this process of reevaluation may not be so necessary in the future.

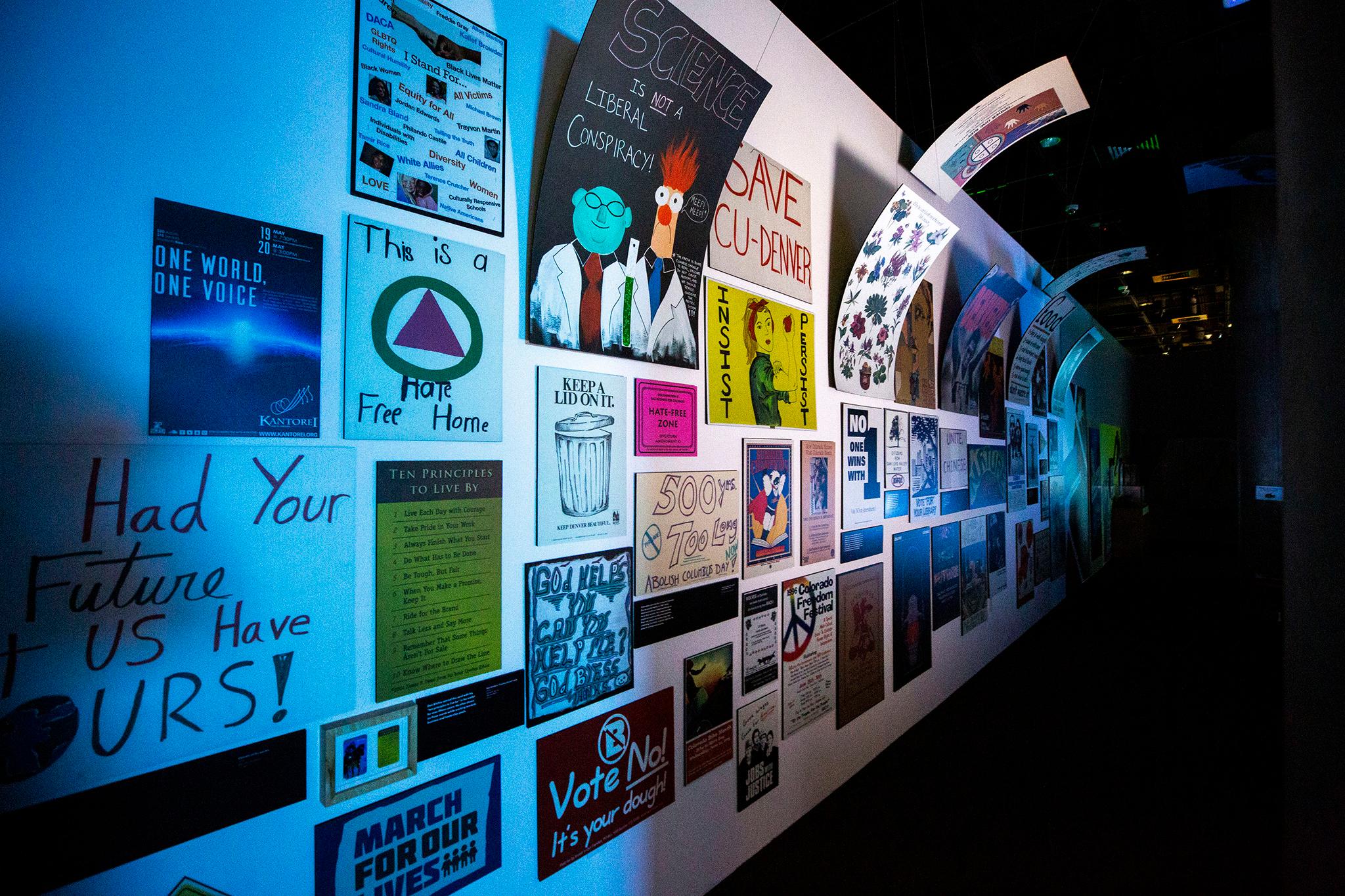

The Women's March in 2017, Seemiller said, was their "first foray" into a community project. They'd never done anything like it. Nearly all of the collections acquired before then came from individuals, usually politicians and important people who recognized their places in history and kept personal archives. The system was set up to preserve the legacies of figures like Corky Gonzales and Temple Buell. Boxes of protest signs, gathered from the masses, was new.

"It was not something that we could ignore," Seemiller said. She realized: "This is going to last forever. We need to document this."

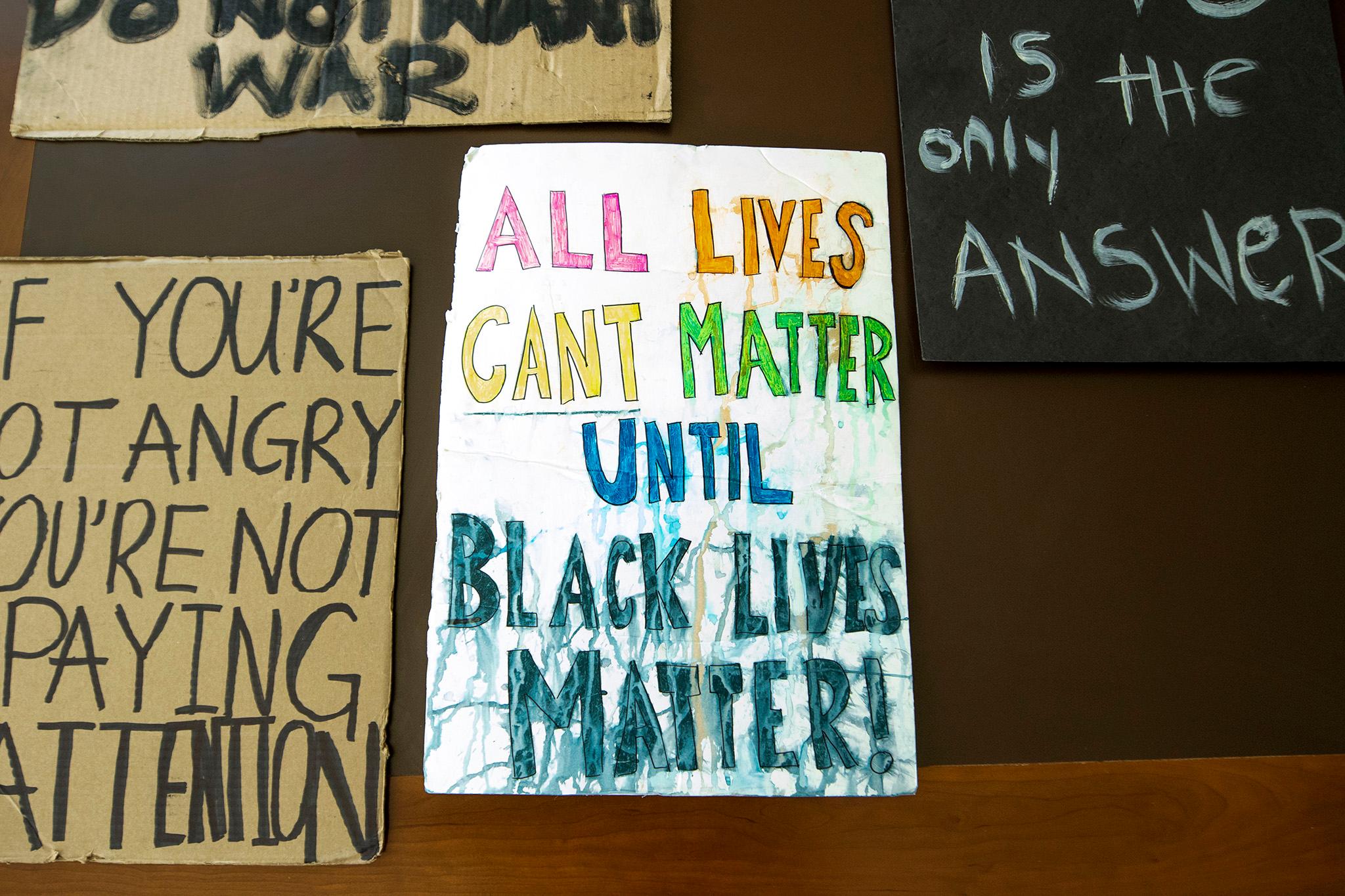

For the Women's March back in 2017, librarians set up a booth outside their front doors on Broadway to ask protesters for their signs. When protests took over the city's streets this summer, the librarians were less comfortable going out amid the tear gas. Instead of collecting items in the moment, Seemiller said librarians went out in the early morning to collect what was left behind. She said the signs collected in this way came with an added layer of context.

"Some of them are torn. Some of them have footprints on them," she said. "It is very powerful to try to preserve these objects."

This year gave librarians a new role. Some on staff are hobbyist photographers, and they went out to photograph businesses covered with plywood in anticipation of the November election. In their effort to document COVID-19, Western History staffers focused on the neighborhoods where they lived, taking photos and talking to people to create another community-driven collection.

"That's the first time that we've done that, asked staff to participate in documenting history," Seemiller said.

Collecting in the present is especially important, she added, because the stories she hopes are preserved may not be seen as important by the people living them. Normal people probably aren't gathering their thoughts in journals and saving documents in boxes.

"That's the hardest part," she said. "A lot of people you want stories from, they're like, 'I didn't keep that stuff.'"

Trust is another issue, too. The library, she said, is "a white privilege institution that was built to control knowledge." Winning that trust, and saving more stories from more people, hinges on archives' abilities to change how they do business.

"The past is our shared story, and we can't represent that shared story unless we have done a good job of collecting the stories of everyone who's always called this place home," History Colorado's Jason Hanson said. "We need to the best we can now, rather than put our descendants in this position that we're in, trying to fill gaps that are incredibly hard to fill 150 years later."

Correction: This story was edited to clarify that Volpe's projects with La Tricolor and Las Mujeres Valientes were separate projects. It also was edited to clarify that History Colorado is not the keeper of the state's "archives," which are official government documents, but its historic "collections," which are museum items. History Colorado is funded by taxpayers, so the items in its collection are still state property.