Editor's note: Kevin and Dave roamed Bruce Randolph Avenue and talked to most everyone they saw. Every day during Street Week, we're rolling out mini profiles of the everyday heroes they found. Find more here.

Head east on Bruce Randolph Avenue through Cole, and you might spot someone watching you. Or some thing. A cylindrical head, mostly consumed by a single gaping eye, hovers over the fenceposts at the corner at Williams Street.

"Big Charles" named is named after a sculptor Shane Evans knows in Atlanta. Charles has a party trick: His chest, thighs, hands and eye can erupt with flames.

On a cold December evening, Evans cracked a Modelo. He'd spent the day tidying up.

"I'm going to get pushed out of here," he said. "If I spent $800,000 on a place, I wouldn't want to look down on somebody's junk."

It's interesting junk, though.

Growing up in Baltimore and Florida, Evans would rummage through bona fide junkyards. He liked messing around with broken-down cars, and he always found beauty in the rubble.

"I'd be at the junkyard quite a bit, and there was always these pieces that were just like little pieces of art to me," he said. "So I started collecting them and started collaging them. Now, I pretty much strictly only try to work with things that I've found. Things that are on the way to the scrapper or the dump. I try to do my best to keep things out of the landfill. That's part of the ethos of what I do."

What he does, precisely, is gather these found objects and shape them into forms that are meant to be set on fire.

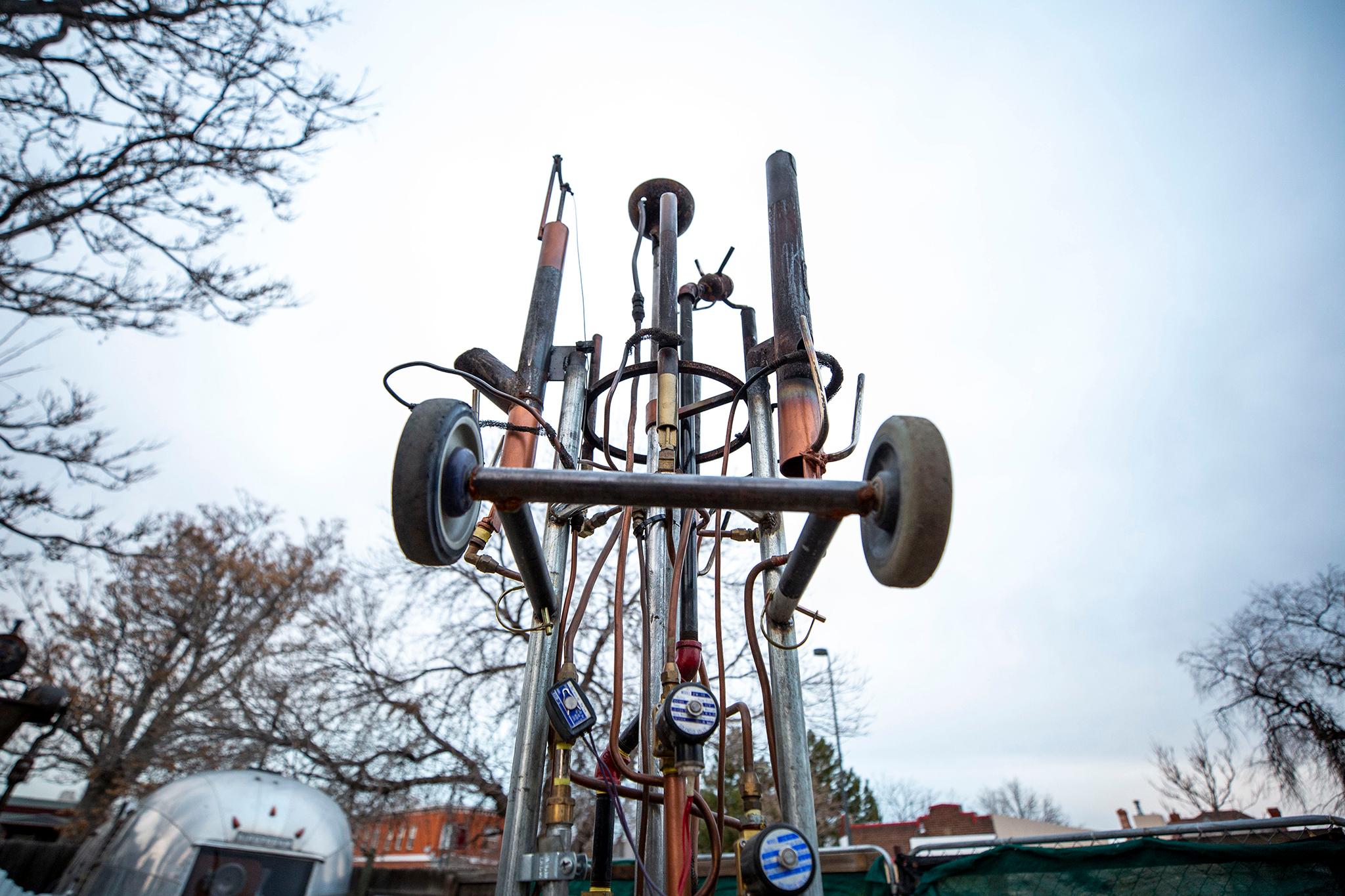

Most are not as tall as Charles, whose stature allows him to peer over the neighborhood. One of Evan's pieces resembles a four- or five-foot-tall human heart. The last time Evans filled it with wood and ignited it, it was in the middle of a river somewhere in the Colorado mountains. Another sculpture is an abstract series of tubes pointed toward the sky.

"Each one of these is a whistle, and they're different pitches. So you can play it like a percussion instrument," he said.

Evans was inspired to build bigger after he first experienced Burning Man. But he doesn't like to think of himself as a "Burner". Instead, he thinks of himself more as a conservationist.

"We live in this really wasteful world," he said. "So many things, they stop working and people just throw them away. And a lot of times, it's just a fuse or just outdated. And it's a shame that that's the world we live in now."

Find the "junk." Turn it into something to behold. That's the mantra around here.

In a way, that's how he viewed the corner lot when he bought it more than a decade ago. His workshop was once an alternator- and starter-repair business. It wasn't fancy, but it provided ample space to build and store his motorcycles. He'd fixed it up over the years, eventually moving his art operation there.

For Evans, making art is an act of escapism.

"I wouldn't say I'm a tortured soul," he said. "But I battled some demons, and this is a way to just escape. I just focus, and the world disappears around me."

He moved to Denver from Brooklyn 16 years ago. He wanted to buy a place of his own, and that wasn't going to happen in New York City.

"I couldn't afford Brooklyn anymore. That was definitely gentrifying, like the true meaning of gentrifying," he said.

So he moved to Cole, purchasing the workshop land and a home a half-block away. The neighborhood had changed significantly in the 40 years before he arrived, and it would change significantly after. But even in 2007, he said, Cole was still "rough."

"I'd walk down to the liquor store, and I'd get harassed just walking," he said. "I had kids throw a brick through my window."

He was a white artist living in an area inhabited mainly by people of color since Denver's redlining policies shifted and started allowing Black residents to move west of Downing Street. Whether anyone saw the writing on the wall 13 years ago, when Evans set up shop, the message grew louder as time passed. White flight was reversing, and things were changing.

In the early days, Evans said, Cole was a great place to build stuff to burn.

"I think that I fit in here because for a while, nobody cared what happened in this neighborhood," he said. "We used to shoot fireballs out of here. I mean, we had the cops here a few times, and they're like, 'Dude. Just put the propane away.'

"It's changed a lot," he continued. "And it's even changed to the point where I'm getting kicked out. My taxes are so high on this place. It's like I either need to start making a lot of income or someone's going to buy it and scrape it and put up some douchey McCondos."

He recognizes that he was an outsider when he arrived.

"I'm probably part of the gentrification, not like I wanted that," he said. "I don't want to see the neighborhood change too much. I don't want to see these bodegas go away.

"I knew it would come. But I guess it did come pretty quick. It came pretty quick," he continued. "Like, as soon as Larimer happened, RiNo. As soon as RiNo hit it -- I don't know. I would have probably bought more places if I had known."