It's been almost a year since Denver B-cycle, one of the first large-scale bike-share systems in America, rolled out of town, dropping the number of publicly available bikes from nearly 1,000 to 250 overnight. Now the city transportation department is gearing up for a new version of a shared micromobility system that will add electric bikes and electric scooters to the mix.

Yes, e-bikes and e-scooters already zip Denverites and tourists around the city. But the new system, expected to be formally announced in February, will streamline things. One or two companies will likely run the show -- whoever gets the contract and a newly created license from the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure. Any companies leftover, even if they currently sling scooters or bikes in the city, will lose their ability to operate, said Heather Burke, a DOTI spokesperson.

"Compared to a permit, the licensed program lays out a shared bike and scooter operation that is the most beneficial to Denver's residents and visitors with selected companies serving as partners to the city to help further the goals of Denver's Mobility Action Plan," Burke wrote in an email.

What will the system look like?

DOTI and its partners are discussing a mixture of dockless vehicles -- untethered e-scooters, e-bikes and pedal bikes, unlocked with an app and tracked by GPS, that riders can dock around the city when they're finished -- and vehicles that people can find at stations, like the old B-cycle system. Unlike B-cycle, those stations might charge the electric scooters and bikes, Burke said.

"We think it should include a variety of options," said Jill Locantore, executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership, which advocates for walking, biking and transit infrastructure. "What we've seen is that Denver residents appreciate a variety of options and really embraced a lot of the different innovations that have come down the pike."

Danny Katz, director of Colorado Public Interest Research Group, said the city is hoping for money from Xcel, which recently got the green light from state regulators to spend money on electric vehicle infrastructure. The utility company is "well-positioned" to aid Denver's micromobility system both with funding and charging infrastructure, he said.

Whoever is selected will have to submit a parking plan and must ensure that sidewalks remain free of the vehicles, according to city documents. Burke said painted parking spots are possible.

The operating license will cover the geographic boundaries of the city.

When will the new system arrive?

Expect an announcement in February. Whoever builds new system should be able to "quickly deploy" the large-scale mobility network after the contracts are signed, according to city documents.

How big will the system will be?

DOTI won't say. We do know at least 20 percent of the vehicles will be bikes, according to the request for qualifications. Ridership data show that bikes are less popular than scooters.

Under the current permitting system (which will become defunct after the new system launches), each e-scooter company is allowed a fleet of 350 and each e-bike company is allowed a fleet of 684. B-cycle had 737 bikes and 89 stations before its demise.

The new bike-share and scooter-share system is part of Denver's plan to meet its sustainable transportation goals, which include bringing Denver's solo driving commutes from around 70 percent (pre-pandemic) down to 50 percent by 2030. DOTI expects the new system to "help the city meet its aggressive mobility goals for reduced single occupancy vehicle use and increased multi-modal trip share," the request for qualifications states.

The system would be scaled according to demand, city documents show.

Who's getting the contracts?

Officially, we do not know who will receive the contracts. DOTI would not grant an interview and is staying tight-lipped on the details of the system because it's still ironing out legally binding agreements with private companies.

Lime, Lyft, Uber, Bird, Razor, Veo and Denver Bike Sharing, the nonprofit that operated B-cycle, were among the companies interested in building out the new network, according to a meeting sign-in sheet from last year. Denver Bike Sharing and Veo partnered on a bid but were not selected, said Sue Baldwin, former director of the nonprofit.

"We were really proud of our proposal," Baldwin said. "We threw everything we had at it."

The other companies either did not respond to requests for information or would not discuss the contracts. Bird, Lyft and Lime all rent scooters in Denver today, while Razor scooters are unavailable, according to its app. Jump Bikes are available around Denver today, too. That company was owned by Uber, but Lime has since acquired it. Confused yet?

Who is the system meant for?

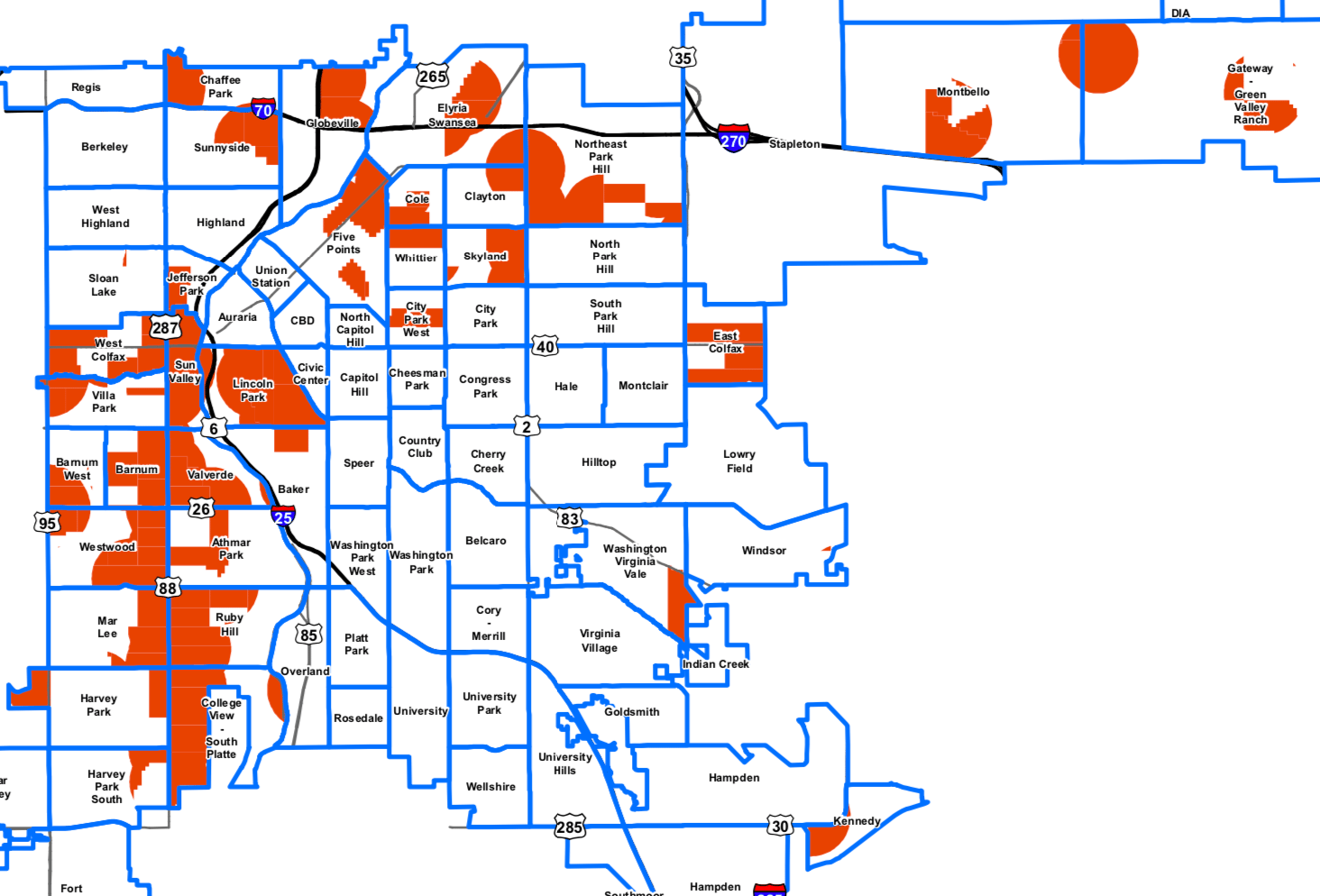

Adults of all ages and children under 18, at least for some vehicles, are the target. So, pretty much everyone. At least 30 percent of vehicles must be made available to areas of the city that have "historically been underinvested" in, with a focus on neighborhoods with low car ownership rates, Burke said in an email.

"Equity is an important goal for the city," the request for qualifications states. "While the proposer is free to redistribute vehicles to meet varying demand by time of day, addressing peak demand should not come at the cost of neglecting certain stations or neighborhoods."

The system should provide "a meaningful quantity" of free or subsidized trips for people to encourage car-free movement, according to city documents. That's in addition to low-income subsidies for low-income riders, Burke said. There will be options for people without banks to use the service.

Locantore is a fan of the city government putting some skin in the game, both with memberships and infrastructure. That means good bike and scooter lanes that make people feel safe on the streets.

"We need to be providing bigger and bigger spaces for micromobility," Locantore said. "Skinny little bike lanes can be problematic if there's not enough room for people to pass each other, going different speeds in those bike lanes.

"There is no form of transportation that pays for itself without some subsidies from the government. And so if we believe that micromobility should be an option that's available to them, then we need to subsidize it just like we do everything else."

Companies will provide free helmets for anyone who asks.

How fast can I go?

When electric bikes and scooters first arrived in Denver, they cruised up to 20 mph. City documents show the speeds will be capped at 15 mph but "reevaluated on a quarterly basis."