When the first COVID-19 vaccines arrived in Denver in mid-December, state and local leaders let out a collective sigh of relief. The vaccines, which are more than 90 percent effective at preventing COVID-19 infections, were a step closer to ending the pandemic, Gov. Jared Polis said at the time.

But a month later, city data shows vaccines are being distributed faster in wealthier and predominantly white communities than in low-income and minority communities.

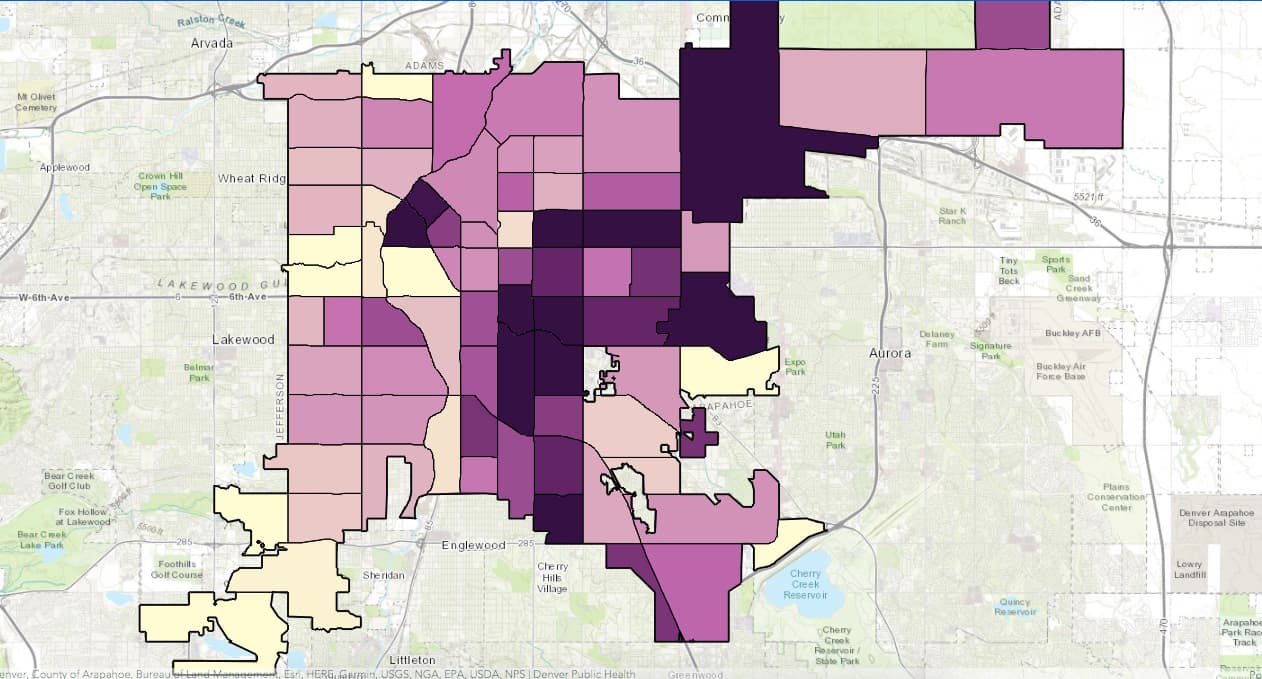

According to data collected by Denver Public Health, the public health arm of Denver Health, vaccine rates in wealthier neighborhoods for residents ages 70 and older are higher than in the city's poorest neighborhoods. For example, during the week of Jan. 11, Bill Burman, head of Denver Public Health, said Central Park's vaccination rate for the 70-plus age group was nearly seven times higher than Valverde's (as of Jan. 20, Central Park's vaccination rate was closer to three times higher than Valverde's). Valverde is nearly 80 percent Latino, while Central Park is 80 percent white, according to city data.

"So, not surprising, but really a reminder to us of the work that needs to be done," Burman said.

The map below, provided by Denver Public Health, shows COVID-19 vaccine rates per 1,000 people ages 70 and older by neighborhood. The darker the neighborhood, the higher the vaccination rate. The findings point to the "inverted L," a pattern that emerges often in city maps that highlights overall inequity. The "L" consists of lower-income neighborhoods with higher populations of people of color.

Health officials in charge of distribution ascribe the disparity to the same set of problems that have made the pandemic harder on communities of color from the start: White people, who tend to have higher incomes in Denver, have better access to healthcare than Latino and African-American residents.

The most recent data from Denver Public Health shows Latinos in Denver make up 46 percent of all COVID-19 cases, while white residents make up 40 percent. Central Park, which is in the northeast corner of the city and roughly five times larger than Valverde by population, currently has a slightly higher COVID-19 infection rate per 1,000 people than the west Denver neighborhood.

The most recent data from Denver Public Health shows Latinos in Denver make up 46 percent of all COVID-19 cases, while white residents make up 40 percent. Central Park, which is in the northeast corner of the city and roughly five times larger than Valverde by population, currently has a slightly higher COVID-19 infection rate per 1,000 people than the west Denver neighborhood.

The city of Denver remains in the "1A" category of its vaccine plan, which includes inoculating people who are 70 and older and certain health care workers and first responders.

Bob McDonald, head of the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, said the city is considering launching a mobile vaccine unit to target underserved neighborhoods. On Thursday, Mayor Michael Hancock's office announced he would host a panel discussion with health experts and leaders in the African American community to discuss historic inequities in health care. The goal of the panel discussions, which will eventually extend into different racial and ethnic populations in Denver, is to encourage vaccinations among people of color. Hancock, who is Black, noted during the Jan. 14 press conference there is historic mistrust of health care among African Americans, who face discrimination in hospitals.

Burman attributed the inequities in vaccination rates to certain populations being less familiar with health care systems and lower insurance rates in low-income populations. A Pew Research Center study in December found that while 60 percent of Americans said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine, only 42 percent of Black Americans said they would. Sixty-three percent of Latinos said they would get the shot, while the rate among white adults was 61 percent.

Of the 70-plus people statewide who have been vaccinated, nearly 74.9 percent have been white, 3.5 percent have been Latino and 1.2 percent have been Black. White people comprise 67.8 percent of Colorado's population, Latinos make up 21.7 percent, and Black residents account for 2.9 percent.

Some of the cities largest vaccine providers -- including the largest, UCHealth -- say they are making strides toward getting more vaccines into underserved areas.

Chief Medical Officer Dr. Jean Kutner said the hospital is hosting vaccination clinics at places where certain communities already congregate. On Sunday, the hospital vaccinated nearly 250 people at the Shorter Community AME Church in Denver, which serves predominantly Black parishioners. UCHealth hosted a similar vaccination clinic at Salud Family Health Center in Aurora on Jan. 14 and 15, helping vaccinate about 500 people. Salud operates 13 clinics around Colorado and focuses on serving "low-income, medically underserved populations as well as the migrant and seasonal farmworker population," according to its website.

Kutner said UCHealth is offering vaccines to patients and non-patients alike, but it isn't asking the latter group about their race or ethnicity. The state recommended that approach, as well as not requiring identification, in a letter to providers dated Jan. 17.

"We hope it is a shared goal to dismantle barriers to access, such as unnecessary identification and patient affiliation requirements," the letter stated.

UCHealth is also translating information about vaccines into different languages and will begin outreach to Spanish-language media.

A spokesperson for the hospital system said that as of Jan. 15, more than 55,000 people aged 70 and older have received a vaccine appointment invitation, and some 17,000 people in that age group had received a first dose.

UCHealth has automatically added existing patients who are 70 or older to its vaccination registry. It has also provided an online registration process for non-patients to get in line for a vaccine, another recommendation from the state. Kutner said people who are in the registry, both patients and non-patients, are then randomly chosen to receive vaccines.

Dr. Judy Shlay, associate director at Denver Public Health, said people 70 and over can get a vaccine by appointment at three of Denver Health's clinics that specialize in serving vulnerable populations, including immigrants and refugees, and people of color: Lowry Family Health Center, Southwest Community Health Center and Westside Family Health Center. Denver Health is also hosting vaccine clinics at different buildings belonging to the Denver Housing Authority that house senior citizens.

Shlay said people who are comfortable using websites or those who are already connected to healthcare systems have gotten their vaccine quicker since they are able to register faster. She said most of those patients have been white. Denver Health has vaccinated 2,557 people aged 70 and over as of Jan. 20. The hospital doesn't formally track racial and ethnic data on people who have gotten vaccinated, per the state's guidelines.

Shlay said the hospital has tried to reach out to underserved communities in more targeted ways, including through texts, phone calls and emails.

"If we see low rates in Sun Valley or Valverde, we know that's a certain type of community we need to outreach to," she said.

Shlay noted that unlike Latino residents in Denver, who tend to live in certain areas of the city, Black residents are not necessarily as concentrated. For that reason, the hospital's outreach to Black residents has to be different, she said. Shlay said outreach efforts to Black residents will include setting up a vaccination clinic, in partnership with the city, at the Center for African American Health in Park Hill.

Shlay said more health care facilities that provide vaccines need to come online to improve access to the shots. So in addition to hospitals, places like pharmacies must become vaccine providers. (The state approves vaccine providers.)

Kutner, who is white, said she has gotten plenty of questions about the vaccine. She recalled an 80-year-old Black woman who asked whether the vaccine trials included people who looked like her.

"To me, it was the smartest question to ask," Kutner said. "To be able to talk to her and explain the trials and explain, yes, the trials, including our own, where we were a site for the Moderna (vaccine) trial, specifically included people from communities of colors and across all age ranges, so that we could be able to answer those questions."

CPR News reporter Andrea Dukakis contributed to this report.