At the Colorado Convention Center, just steps away from the Big Blue Bear, Understudy's latest fishbowl exhibition offers a time capsule beyond glass: a glimpse into the life's work of a group of prolific light artists.

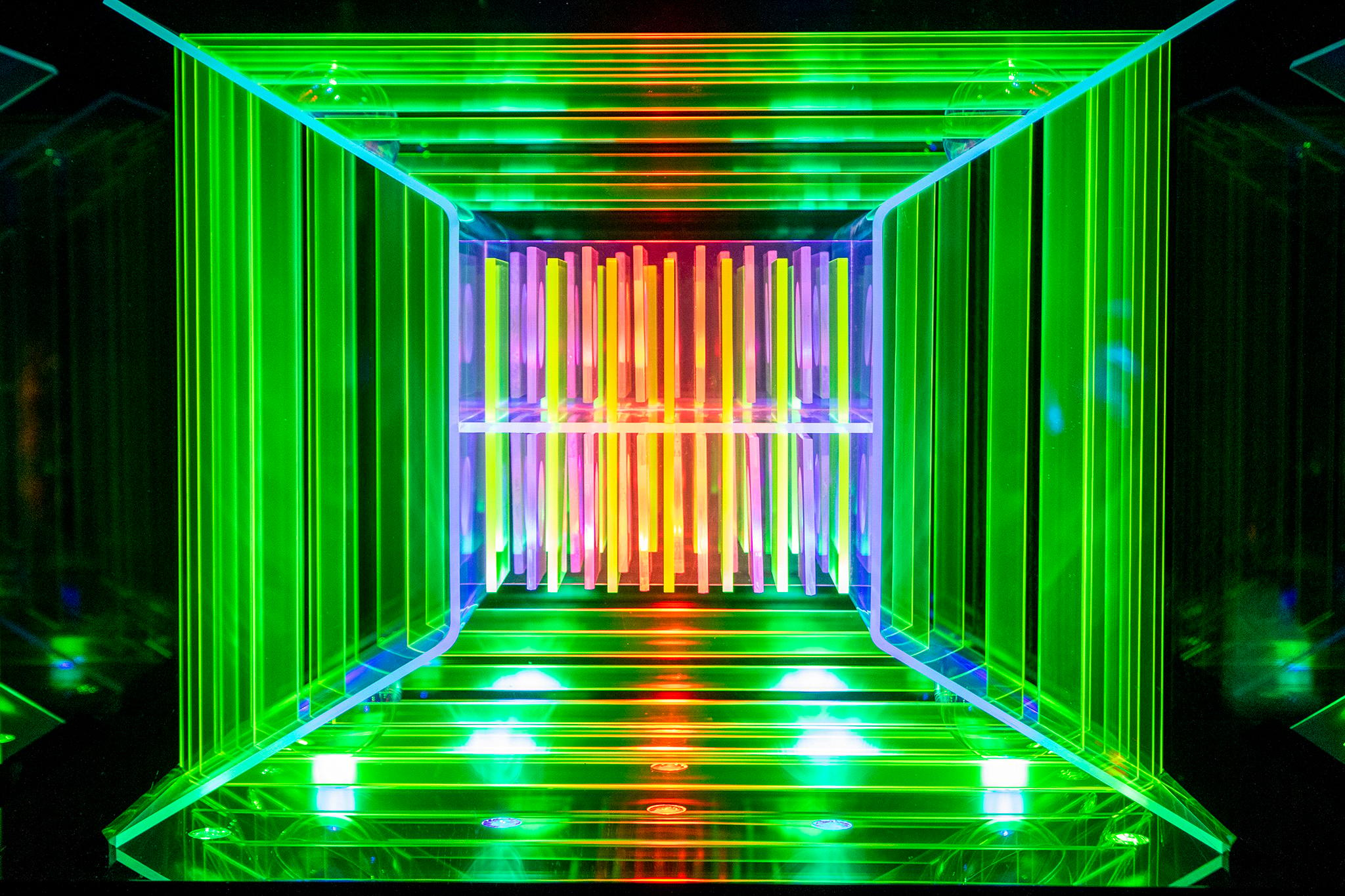

Lumonics Mind Spa: Light Intersection is a collection of work by the Denver-based light art group Lumonics -- specifically, the work of its late founders, Mel and Dorothy Tanner. Through January 31, visitors to the installation can stand on the sidewalk, peer through the glass and soak in the art: a series of colorful, LED-illuminated plexiglass sculptures best viewed at night.

This work is one of several of what Dorothy Tanner called "mind spas": light art displays designed to be a soothing retreat for the mind. Thadeaous Mighell, the Operations Director and Marketing & Development Manager at Understudy Arts Incubator Space, said viewing the Understudy mind spa is a meditative experience.

"If you've ever experienced light therapy, I'd liken it a lot to that," Mighell said. "It's very serious and somber. I wouldn't say in a depressing way, but kinda when you go to a therapy session, or when you go to meditate."

"It's so abstract that there's nothing to really compare it to," said Barry Raphael, a Lumonics crewmember in charge of the group's social media, website and publicity. "It has a dreamlike quality to it. It's very relaxing, and you're free to have your mind wander."

Founded in the 1960s, Lumonics is considered one of the first and longest-standing light art studios in the U.S. Its members, each of whom is now over the age of 70, travelled together all over the country before landing at last in Denver, where they share both a house and a studio space. Today, decades after the group formed, its numbers are dwindling. Dorothy Tanner died last July at the age of 97. Her husband and cofounder, Mel, died in 1993. The group's remaining members are working to keep the collective alive and to bring their work to a new audience.

Many have labeled the folks at Lumonics "counterculturalists." Mighell goes so far as to call them "counterculture to the counterculturalists," saying that the group seems to exist in its own bubble within Denver's arts scene. But they themselves are hesitant to define themselves or their work, insisting that what they do is beyond words.

"One thing we haven't done is actually say out loud, 'We are this.' We are who we are in this space. And the art is what it is," said Marc Billard, an artist, videographer, photographer and musician at Lumonics who's also been curating Lumonics' projects in Dorothy's absence, including the one at Understudy. "I mean, mucho people have told us, 'You really got to put this on paper, so it can be read, and present yourself in the proper way for this world. And we don't do that, much to our advantage and, I suppose, economic disadvantage."

The Tanners began as traditional artists. Mel was an abstract painter, Dorothy a sculptor. In the late 60s, they started experimenting with acrylics, excited about the possibilities for color and light transmission they presented. They opened their first light art exhibition at a stereo store in Miami.

One sunny Florida day, they stepped out of the shop to visit a nearby diner. As they walked across the parking lot, Mel glanced up at a plane overhead. It was a shiny, silver metallic aircraft, and as he looked at it, he saw his own reflection from the other side of the parking lot, staring back at himself.

"It was the most powerful experience that ever happened to him. It's like he connected with another part of himself," Raphael said. "He was just, like, a transformed person."

That moment helped spawn the first Lumonics Light and Sound Theatre in 1969: an immersive light and sound art experience set in a remote Miami studio.

Rick Spisak, who's now a multimedia content creator and teacher based in Florida, was one of the first people to visit the theatre. He was a high schooler at the time and deeply interested in the arts.

Spisak arrived in the warehouse district at night. It was nothing but row after row of nondescript buildings, each with industrial commercial signage. The Lumonics building was the same: a warehouse by the tracks, where a Little Haiti Cultural Center now stands. Nothing could be more mundane, Spisak said.

"Just a nothing sort of place, right by the edge of the railroad tracks," he said.

The only thing distinguishing it was a tiny plaque that read "Lumonics" in plexiglass letters.

"When we walked in, it was absolutely transformational," Spisak said. "It was a voyage into a different kind of universe completely."

He walked into a darkened room with black walls, illuminated by glowing lucite plastic sculptures all around. Some had water dripping through them, some were pulsing to the music. He was greeted by a Lumonics member and ushered through a mirrored door into the main room.

"It was literally like being inside someone's mind," he said.

The whole space moved and pulsed with light, and the sculptures all around him pulsed with music, sometimes Beethoven, sometimes Tchaikovsky, maybe Pink Floyd, Jeff Beck or Moody Blues. Images projected on different surfaces as soothing sounds -- birds, insects, subtle instrumentals -- filled the room. Every movement gently transitioned into the next, and the whole room was moving and glowing.

"Even the restroom was an experience in itself," Spisak said. "There's mylar mirror floor to ceiling all around you. And because it was wisely not tacked down closely, every breath, every movement, made the mylar shift and change and move. So your reflection was constantly shifting."

The people of Lumonics seemed to be quiet and soft-spoken. They looked identical: all slight, relatively short, with bowl cut white-blonde hair. They all dressed in black and moved quietly through the crowds, assisting patrons and answering questions.

"You would have expected them to have walked off a UFO somewhere," Spisak said.

After visitors soaked in the ambience for a while, they were led to bean bag chairs and waterbeds, pillows, inflatables and foam pieces all over the floor. They were invited to relax, have a drink, kick off their shoes, as if they were in someone's living room.

Then the light show would begin. From a mezzanine balcony, Mel and Dorothy would play the light pieces electronically using a keyboard. Lazers, strobes, sculptures and projections would move, synched to the music. Mel would place slides in a projector, blow them to the size of a 20-by-20 wall and create live paintings. For Spisak and many others, the show defied description.

"The experience itself was so overwhelming that at the end of the evening, people really had a little trouble getting up," Raphael said. "One of the best compliments I ever got was, somebody came in from out of town. They were living in New Mexico. And at the end of the evening, he said to me, 'Is this legal?'"

Some visitors told the folks at Lumonics they even underwent emotional breakthroughs, past-life regressions or encounters with relatives who had passed.

"Some really wild things have gone on," Raphael said.

Spisak said he remained silent after the show, amazed at the impact of the nonverbal art experience.

"Those people did so much good. They took people outside themselves," he said. "They took them to a place where it was pure light and pure sound. And they got outside the cage of words, got outside the cage of the narrative arc. And until you've been outside that cage, you don't have any idea of the riches that are there."

Raphael had been teaching junior high in Chicago in 1971 when he first heard of Lumonics.

"I was personally looking for a breakthrough in my own life," he said.

A family friend who was teaching in Miami reached out to Raphael to tell him about an incredible experience he'd just had. He invited Raphael to come down to Miami over Christmas break to see Lumonics for himself.

"As soon as I saw it, I said, 'Ah, this is what I wanna do. I want to be part of this,'" Raphael said. "It was so powerful."

In the winter of 1972, Raphael moved down to Miami to join Lumonics.

At that time, Marc Billard was a carpenter working on expensive houses in the Coral Gables area.

"I was just trying to figure out my life," he said. "I didn't know what I really wanted to do. Wanted to do something interesting, but I was in construction."

He lived in an apartment in Coconut Grove, next to Mel's sister Jocelyn, who was a Lumonics member and a big promoter of the arts. One day, Jocelyn told Billard he had to come see what her brother was doing. Billard said he finally went a year later, after "much sweating in the south Florida sun." He walked through a warehouse door into another world, a "far-out" looking place.

"I was just absolutely blown away," he said. "I was always kind of... not spaced out, but slightly removed. Couldn't really line myself up to this world. And this was an alternate universe that you could just walk in and just be in another place, completely."

That whole night, Billard sat in his thoughts. Everyone else was sitting around, talking and getting stoned. But Billard was silent.

At the end of the night, Mel asked Billard if he'd like to come by and work. He said, "Sure."

Shortly after him, Barbara, Marc's wife, came on, and the core Lumonics group had formed: Barry Raphael, Marc and Barbara Billard, Mel's sister Jocelyn, and Mel and Dorothy Tanner.

"And we've all been together ever since," Raphael said.

Part of the allure of Lumonics was the couple leading it.

"I kind of fell in love with Mel and Dorothy when I met them," Raphael said. "They were just fantastic people."

He said they were modest and humble and didn't judge. They were more interested in creating the experience for people than they were in creating work to sell.

Mel was quiet and meditative and loved to laugh, Raphael said.

"Just so dear. And anybody that would meet him would really kind of fall in love with him," Raphael said. "He could communicate deeply with anyone he met, in a very deep, connected way."

Dorothy was more extroverted and outgoing. That seemed to work well for them.

"They were a very powerful team," Raphael said.

Dorothy was fearless, straightforward. She had a knack for getting people to open up to her, to trust her with things they might usually keep to themselves. While Mel would sketch all his pieces out meticulously beforehand, Dorothy would improvise, taking discarded cutoffs from old projects to create something new.

"She was a wild character. I mean, she really was," Billard said. "She would pull in ideas from God-knows -- dissonant aspects of the world, ideas and stuff -- and put them together in a piece."

Lumonics functioned as a collective, a kind of "economic commune," Billard said. The Tanners offered to pay him what he needed for rent and food or whatever he needed.

"I was totally amenable to whatever was going down," Billard said. "I had nowhere else I'd rather go, and nothing else I'd rather do, and nobody else I'd rather be."

In 1979, they all moved together to Encinitas, Calif. They rented a big, beautiful redwood house and decked it out with light art. That was the first time they lived together.

"It was very new for all of us. And we got along very well," Raphael said.

He said that they never got sick of each other. It worked because they were all so dedicated to Lumonics.

"Living and work just kind of all became one," he said.

They were living without structure, making it up as they went along. They would sometimes take on odd jobs, commissions and commercial work to help keep the experience alive. They'd do pieces for people's private residences, for nightclubs and discotheques. The live performances never made much money.

"They were just devoted to providing the experience for people," Raphael said.

People often are surprised at the group's communal lifestyle, but Billard said the group didn't ever really fight. When personalities clashed, it was on each individual to work it out on their own.

"We were a family," Billard said. "So how does a family get along? Well, you can either get along badly, or you can be mad at your parents the rest of your life, or not."

They moved around for a few years before returning to Florida. They rented a house in Fort Lauderdale, and stayed there for several years. It was there that Mel passed away at the age of 68.

Billard was shocked to see Mel go so soon. But Mel felt it was his time to go, that he'd done everything he needed to in this world. Billard was worried about how Lumonics would function without him.

"When we got home after he passed, I got high as a kite on my own," Billard said. "And it's like, OK, everything that went down before, don't worry about it. We're gonna do a new thing."

So they broke out some of what Billard calls "fake champagne": white wine mixed with seltzer.

"We got a little high on that. And we danced," he said. "We had a dance party on the night that Mel passed. And everyone got happy."

Mel had been more or less the head of Lumonics. After he passed, Dorothy stepped up and started pursuing more of her own ideas. They moved away from live performance, feeling that they couldn't replicate the experience without Mel. Dorothy began to work with LEDs and forge her own style of light sculpting. Billard got into computers and synth, and he and Dorothy started creating music and video together.

"It got pretty far out," Billard said.

In the late 2000s, the collective began looking around for a new place to live. They considered Vancouver, California, and other parts of Florida. Then, Dorothy and the Billards took a trip to Denver and decided that was the place. Marc Billard said that Lumonics' vibe seemed to work in Denver.

"The vibe in Denver is freer. And grass was legal," he said, adding that while he himself isn't a big smoker, Dorothy definitely was.

They rented a house in Denver in 2009, opening their own studio in an old warehouse in north Denver. There, they work, display their art and host events. They also started the Lumonics School of Light Art in 2018 to teach a new generation how to create their own light art.

In 2018, they opened the first Lumonics Mind Spa in the McNichols Building, which became the space's longest-running exhibition. That year, at the age of 95, Dorothy was granted the Excellence in Arts & Culture Innovation Award by Mayor Michael Hancock for her innovative work.

"Dorothy was in her early 40s when she began doing the light art," Raphael said. "For a lot of people, that's very inspiring, because some people think Jesus, you know, I'm, 30, it's too late for me to do anything. And so Dorothy is really a great example of somebody that just didn't let age stop her."

Dorothy continued to work even as her health declined. When the group still lived in Fort Lauderdale, Dorothy was diagnosed with macular degeneration. Raphael said a bad surgery left her blind in one eye.

"It took, oh, six, eight, ten months for her to start working again, because she got really kind of depressed about it," Billard said. She was eventually diagnosed with glaucoma as well.

"It was kind of a one-two punch," Raphael said.

As a visual artist, it was difficult for Dorothy to watch herself lose her vision, but she stayed creative, working on sculptures like script pieces that were easier on her eyes.

A couple of years ago, Billard said, Dorothy started slowing down. She had less and less energy for work. Soon, the people she'd lived and worked with for decades became her caretakers.

"I didn't really leave for more than an hour or two for, I don't know, since March," Billard said. "Made me nervous not to be around her and care for her, just do whatever we could."

She passed away at the age of 97, on July 23, 2020. When word got out about her death, people from all over called and emailed Lumonics to say what she'd meant to them.

"There's so much love pouring into her," Billard said. "She affected so many people."

Thadeaous Mighell thinks there's something to be learned from the way the folks at Lumonics deal with death. He said he spoke to them not long after Dorothy passed.

"It didn't seem to impact them negatively, as death often does," Mighell said. "They talked about her almost as if she was still around, like she just went for coffee or something and would be right back."

Billard said Mel and Dorothy left when they were ready.

"They had done what they were supposed to do," he said. " I certainly felt that with Dorothy. I felt that with Mel."

The group keeps them close, Raphael said. "We're surrounded by the artwork."

There are a lot of new things ahead for Lumonics.

The group has been contacted by someone in Boulder County about designing some outdoor light sculptures, which Dorothy had always been interested in pursuing. Members are considering exploring the possibility of interactive light art that would be controlled using a cellphone app. And Mel and Dorothy's work will be featured in the opening gallery at Meow Wolf Denver when it opens next fall.

They're also thinking about getting a bigger studio space in Denver to allow for a more complete Lumonics experience, an idea Dorothy had before she died. It would be a museum and an art school, an event center and a healing center.

"That would be a way of really getting the work out there," Raphael said. "And a more of a permanent space that could actually just continue to be, after our lives are over. Something for the people."

In the past, Dorothy had typically been the one who curated Lumonics projects. As her health declined over the years, Billard took on more responsibility, stepping up to create and curate Lumonics works. Now, Billard is sorting through a catalogue of decades of old Lumonics works to present to a new audience. He's pulling old audio and video from the archives and transitioning them to HD, playing with the footage and entering his work into festivals. He's also working on music projects, revisiting sounds he'd created with Dorothy that had seemed too wild at the time but which might resonate better today.

"It's interesting, having a backlog of 20, 30 years of material, sounds, images, videos, all that kind of stuff. And you can bring it into the future in different ways now," he said. "Everything is changed. It's wild. So I'm having a lot of fun with that."

When it comes to the art itself, Billard's determined to create something new and to do it in the right way for himself.

"I have to find a path for me to get into things where I'm not copying somebody. It's like my own kind of thing," Billard said. "And it will have the vibration of Lumonics. But it really hasn't shown itself. I'm not in a tremendous hurry."