Last month, Smith's Chapel in Lincoln Park became Denver's 350th landmark.

On the surface, that number already looked pretty special. But the process to get there was even more unique, because no other building got the tag the way the Gothic Revival-style chapel did.

The Chapel was the first property to earn the landmark distinction under a new criteria introduced in 2019. The city's landmark preservation law, which provides rules for how a building can be deemed a landmark, was updated that year to include three "cultural significance" criteria for eligibility.

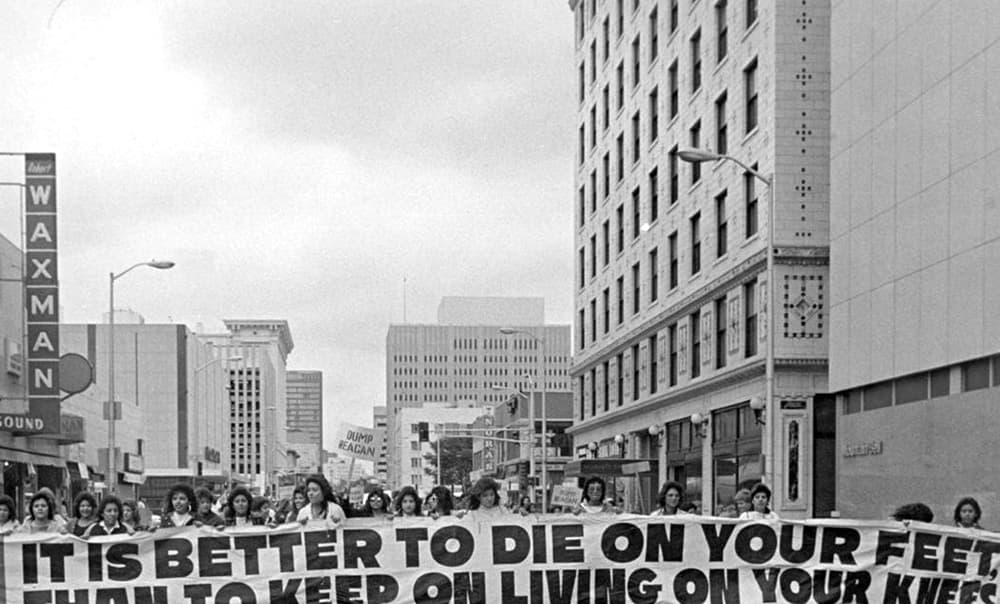

These new criteria mean buildings can qualify because of their cultural connection to an era in the city's history. In this case, the chapel, which was completed in 1882, met the criteria thanks to its connection with a social movement -- specifically the Chicano Movement in Denver. The movement sought to combat racism, support worker's rights, education, housing and land rights. The chapel became a neighborhood hub for Chicanos to meet and socialize.

Anybody tuning into the City Council meeting on Dec. 21 got a crash course on the Chicano Movement in Denver.

The same night City Council unanimously approved Smith's Chapel as a landmark, it also approved renaming Columbus Park to La Raza Park, which was another epicenter of Chicano history in the city's Northside.

Smith's Chapel was sold or deeded to the Denver Inner City Parish by the United Brethren Church in the early 1960s, according to city documents. Former Denver Inner City Parish executive director Lisa Flores, who worked there from 1998 to 2003, said the parish started in the 1960s with a focus on providing community services. It received support from several metro area churches, most of which were Protestant. The money helped fund a food bank, provide student tutoring and an art space.

Flores knew the chapel's history when she took over as director after several years of volunteering there. She noted the chapel's role not only in Chicano history, but the city's history as a whole. The organization offered after school programs, ran classes for teenage fathers and raised money to help recently incarcerated people get back on their feet. Because of the parish's work, these programs existed here before they became commonplace in the city.

"They have been serving the Chicano community in this way for decades," Flores said.

The chapel became a respite during a nascent chapter in the Chicano Movement's history in Denver.

In March 1969, West High School Chicano students stormed out of their school to protest treatment by staff. At the time, some staff members discouraged students from speaking Spanish and ridiculed their names by purposefully mispronouncing them.

After walking out to demonstrate at Sunken Gardens Park, students clashed with police, who used pepper spray on the young activists. Students from other city high schools joined the demonstrations. The confrontation led to four days of unrest later known as the West High School blowouts. Some of the students and demonstrators took refuge inside Smith's Chapel as the clashes intensified, according to city documents.

Steve Johnsen remembers watching the events play out. He was a volunteer at the Inner City Parish when the blowouts happened, and said a friend who worked at the parish told him that, as a white person, he was better off staying inside.

Johnsen, who would spend nearly five decades working at the parish, including a stint as an executive director and principal of a school based inside the chapel, was in his 20s during the blowouts. He remembers seeing demonstrators turn over a police car and hearing Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales, who would go on to become a leader in the Chicano Movement, deliver a speech outside the chapel.

"I was watching the whole first day, (watching) the walkouts happened," Johnsen said, adding he had been told the demonstrations were connected to a racist teacher. "It was probably the times, too. Everybody was doing stuff like that, all over the country."

Smith Chapel's owner, Matt Slaby, is a photographer by trade. He was born and raised in Denver. Slaby bought the building in 2019 and now operates a media agency inside. He hopes to draw similar businesses, adding that it's much larger than what he needs for his work.

From the very beginning, he wanted to make sure the building stayed the way it's been for decades. Familiar with its history, he said he intended to keep it as an asset for people in the neighborhood. He didn't want the site to end up demolished for something like, say, new condominiums.

"That wasn't really a story I wanted to be a part of," Slaby said. "It has a really long and nice story."