A young program that puts troubled nonviolent people in the hands of health care workers instead of police officers has proven successful in its first six months, according to a progress report.

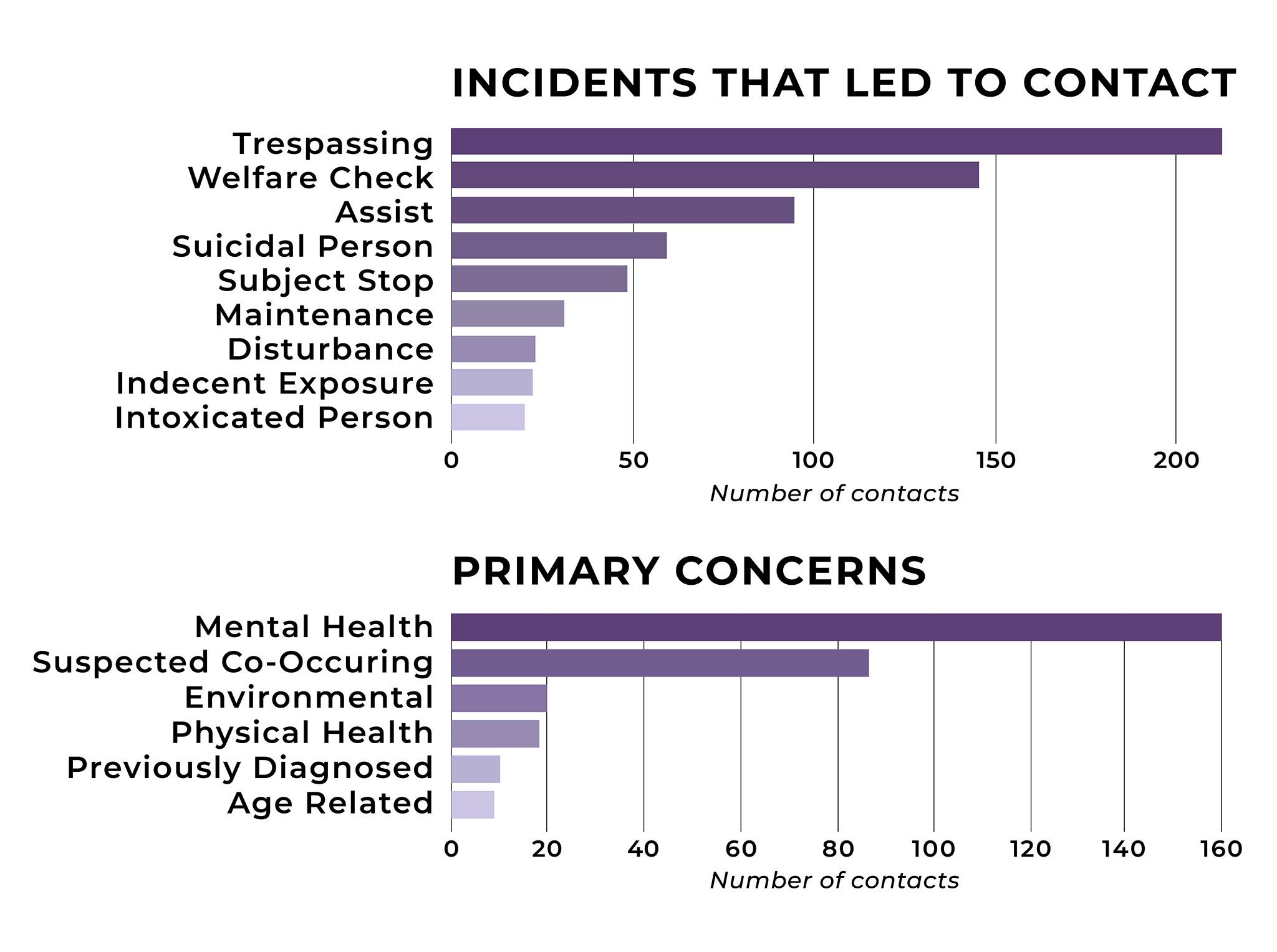

Since June 1, 2020, a mental health clinician and a paramedic have traveled around the city in a white van handling low-level incidents, like trespassing and mental health episodes, that would have otherwise fallen to patrol officers with badges and guns. In its first six months, the Support Team Assisted Response program, or STAR, has responded to 748 incidents. None required police or led to arrests or jail time.

The civilian team handled close to six incidents a day from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday through Friday, in high-demand neighborhoods. STAR does not yet have enough people or vans to respond to every nonviolent incident, but about 3 percent of calls for DPD service, or over 2,500 incidents, were worthy of the alternative approach, according to the report.

STAR represents a more empathetic approach to policing that keeps people out of an often-cyclical criminal justice system by connecting people with services like shelter, food aid, counseling, and medication. The program also deliberately cuts down on encounters between uniformed officers and civilians.

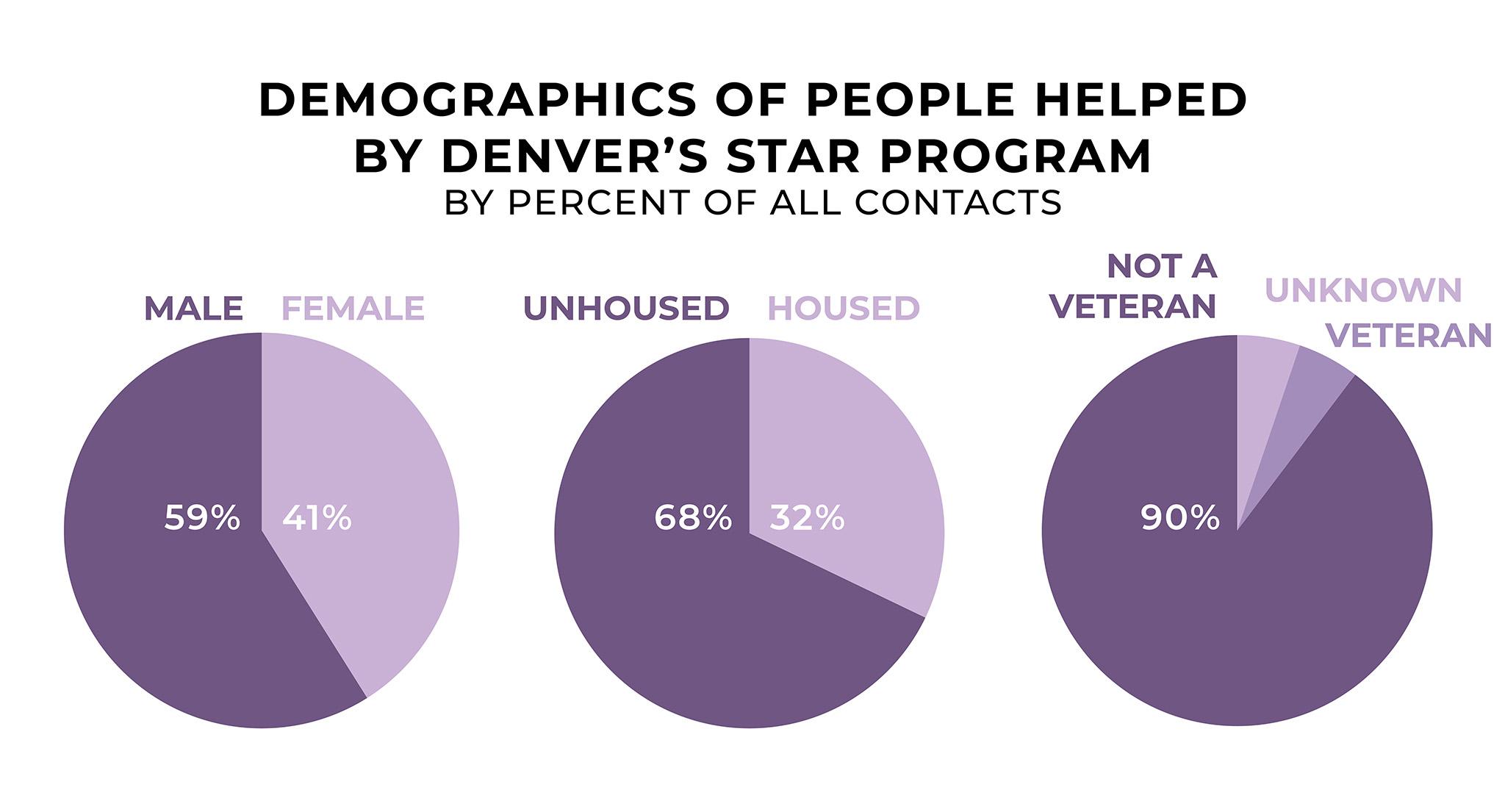

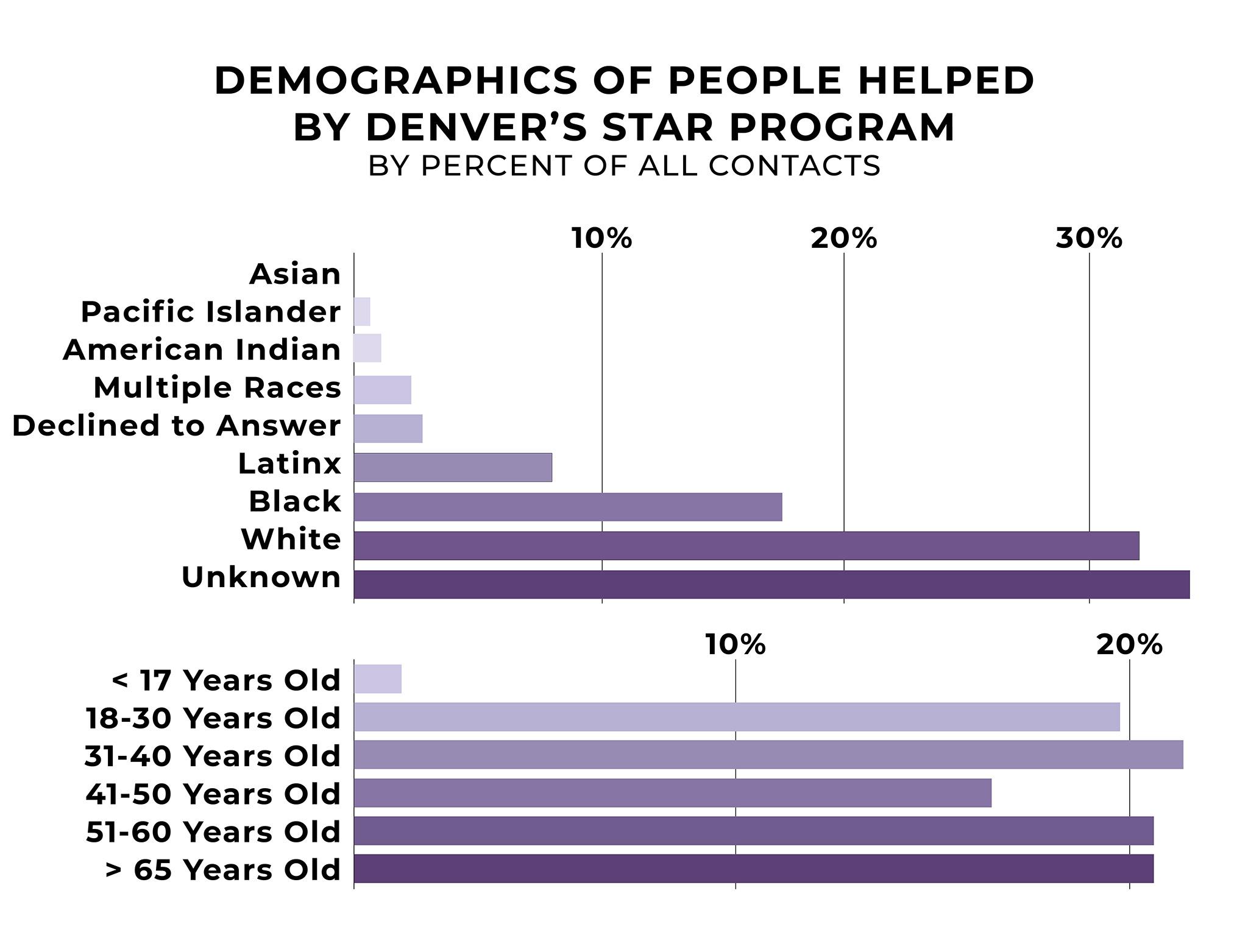

Source: Denver's STAR Program

"This is good stuff, it's a great program, and basically, the report tells us what we believed," said Chief of Police Paul Pazen. Pazen added that he doesn't want to sound flippant, but the approach was somewhat of a known quantity because he's been talking about it with advocates for mental health and criminal justice reform for years. Denver just so happened to launch the program in the middle of a movement against police violence.

Pazen's goal is to fill out the alternative program so that every neighborhood can use its services at all hours, instead of just weekdays during normal business hours. Nearly $3 million for more social workers and more vans should help Denver move toward that "North Star" this year, Pazen said. The money is expected to come from the city budget and a grant from Denver's sales-tax-funded mental health fund.

Carleigh Sailon, one of two civilian social workers on the team, said more vans -- and more food and blankets to go with them -- as well as weekend and after-hour shifts will do big things for the program.

"We run an unbelievable amount of calls for such a limited pilot program and have had some really good outcomes on those calls," Sailon said.

The policing alternative empowers behavioral health experts to call the shots, even when police officers are around.

Sailon said she remembers a call last year in which a woman was experiencing mental health symptoms at a 7-Eleven. The clerk had called the police -- the woman was technically trespassing -- but when the police arrived, they called Sailon.

"We got there and told police they could leave," Sailon said. "We didn't need them there."

The woman, who was unhoused, was upset about some issues she was having on her prepaid Social Security card. Sailon helped her into the van where the two "game-planned" a solution before the STAR crew drove her to a day shelter for some food, she said.

"So we were sort of able to solve those problems in the moment for her and got the police back in service, dealing with a law enforcement call," Sailon said.

The fact that the police officers even called the STAR team tells Dr. Matthew Lunn, who is in charge of DPD's strategic initiatives, that the program is working (Lunn has a PhD but is not a medical doctor). About 35 percent of calls to STAR personnel come from police officers, according to the report.

Source: Denver's STAR Program

"I think it shows how much officers are buying into this, realizing that these individuals need a focused level of care," said Lunn, who authored the report.

No one really needs any more evidence that this alternative to traditional policing works, but Sailon and Lunn said more data will make STAR stronger. For example, while STAR might steer people away from jails and courts initially, the long-term effects of the program must be studied, the report states.

Source: Denver's STAR Program

Chief Pazen is thrilled with the success of STAR, but the time and money it saves will go toward fighting crime, he said.

A spectrum of solutions has sprouted from protests against systemic racism and police brutality that started last summer, including the idea of taking money from traditional policing and giving it to social programs not unlike STAR.

For Pazen, transferring low-level calls to civilian teams is not about reallocating money. It's about solving two problems at once: getting harmless residents the help they need while letting police focus on other things.

"I want the police department to focus on police issues," Pazen said. "We have more than enough work with regards to violent crime, property crime and traffic safety, and if something like STAR or any other support system can lighten the load on mental health calls for service, substance abuse calls for service, and low-level issues, that frees up law enforcement to address crime issues."

Pazen added: "I see this as an 'and.' Not an 'or.'"

This article was updated to clarify that Lunn holds a doctorate but is not a medical doctor.