If you add up the space in Denver where people actually live their lives -- all the neighborhoods, parks, roads, schools -- you're left with an area equaling roughly 116 square miles not including the airport. That's roughly 56,000 football fields (don't ask how we know that).

Yet, for marijuana dispensaries, most of that space is unavailable. While you may see dispensaries along major corridors like Colfax Avenue and Federal Boulevard, most of the city is actually off-limits to storefronts selling marijuana.

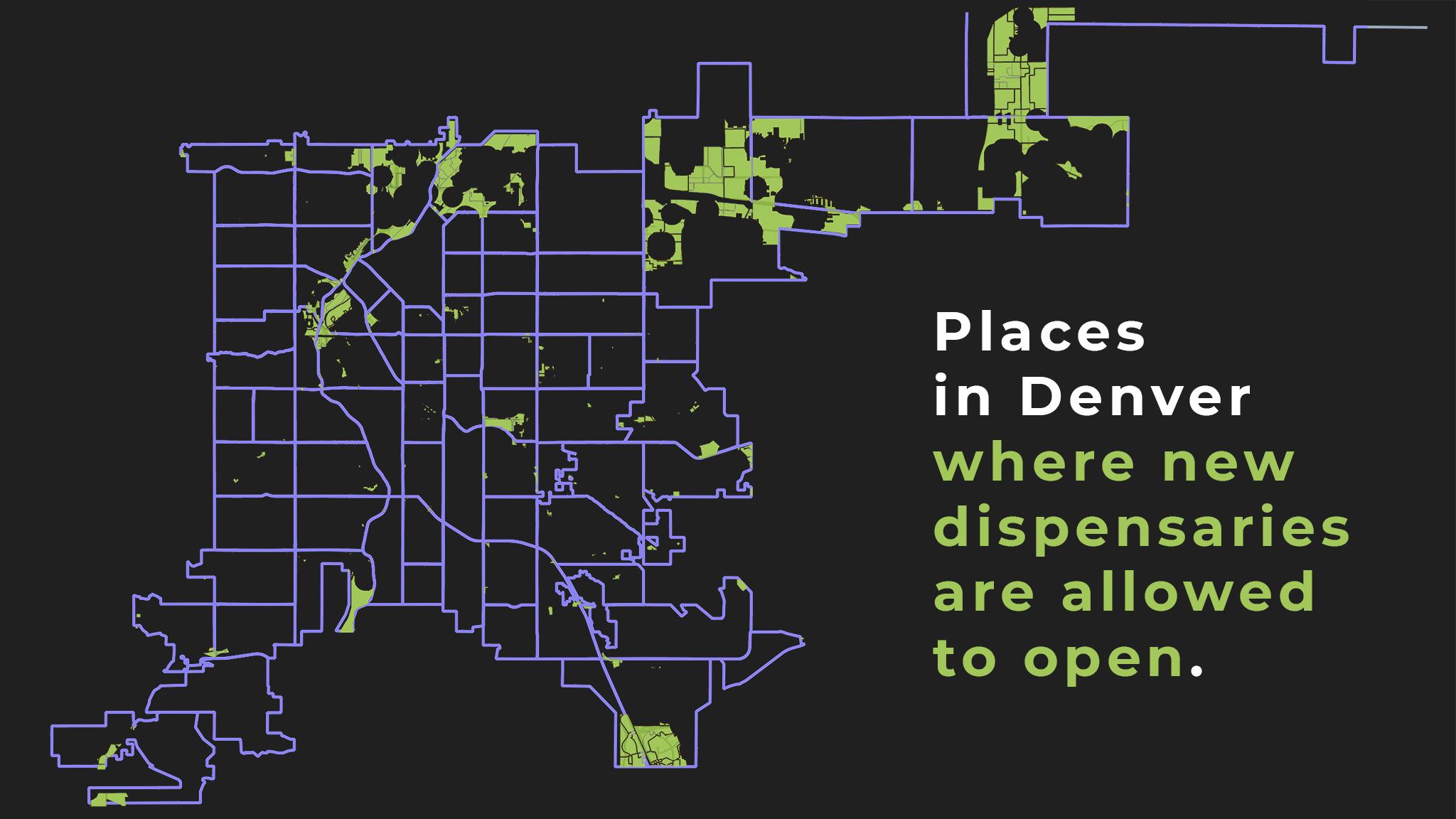

Like, a lot of the city. Nearly 70 percent of Denver can't have a dispensary due to the city's zoning code, or the laws outlining what can and cannot be built somewhere. Another 14 percent is off limits to dispensaries because of rules put in place after the state legalized recreational marijuana in 2012. Dispensaries in Denver have to be 1,000 feet away from schools, childcare facilities, other dispensaries and drug treatment facilities. Another 7.50 percent of the city is unavailable due to regulations that aim to prevent an oversaturation of dispensaries in neighborhoods where there are already a bunch. Those neighborhoods are Baker, Five Points, Northeast Park Hill, Overland and Valverde.

"We don't want to see it where one neighborhood is completely saturated and other neighborhoods have don't have many businesses," said Eric Escudero, a spokesperson with the Denver Department of Excise and Licenses, the city agency that oversees licensing for the marijuana industry. "It shouldn't be one neighborhood to have all the marijuana businesses."

Mix in a few more restricted areas, and only 9.5 percent of the city -- 10.89 square miles, or 5,270 football fields -- can accommodate dispensaries.

As Denver City Council considers overhauling the city's marijuana laws, a big change among the proposals would open applications for new retail store locations for the first time since 2016. City Council is expected to vote on the new laws on April 19.

Our map shows where ganjapreneurs could open up shop now, which, depending on whom you ask, is not as easy as it sounds.

Space is still available in several areas, including Central Park, Green Valley Ranch and Elyria Swansea (and chunks of Southmoor Park, Hampden South and College View-South Platte).

But people in the industry argue that doesn't mean that space is guaranteed.

Hashim Coates, executive director at Black Brown and Red Badged, an organization supporting Black and brown marijuana business owners in the state, said that because of the current restrictions, folks in the industry aren't having much luck finding space to open up shop.

"They can't find anything," Coates said.

That's especially true for Black and brown people trying to break into the overwhelmingly white industry. A study released by the city last June showed 75 percent of owners and 68 percent of employees were white. Nearly 80 percent of respondents cited access to capital as a barrier for entering the industry.

Robb Brown runs a retail consulting firm in Denver. He's helped dispensary owners rent and buy spaces for retail sales. He said his complaints often cite the 1,000-foot buffer as the main reason why it's so hard to find space in Denver. Schools and other off-limit areas are pervasive in a city where affordable real estate is nearly impossible to come by.

But Escudero and Brown both said the pandemic might have made more retail space available since so many businesses have closed. A recent report from CBRE, a commercial property brokerage company, said retail vacancy rose by 1 percent in 2020, to a 7.8 percent vacancy rate. That might not seem like a lot, but CBRE said that was an 8-year high for the metro area retail market.

Escudero said that when Denver started out recreational sales in January 2014, the city was in completely uncharted territory.

Denver was the first major city in the country -- actually, in the world -- to legally sell weed this way.

"We had no one to look at and say, 'Hey, how did Boston do? Or how does Seattle do, or what lessons did they learn?'" Escudero said. "We had to build the plane as we're flying it."

The city now has nearly a decade's worth of data and knowledge about sales. It's put some of that to use as it looks to revamp the city's weed laws.

Escudero said if the proposed laws pass City Council, the neighborhoods in Denver oversaturated by dispensaries may change (the department determines oversaturation by finding the five neighborhoods with the highest concentration of dispensaries). Because the proposed laws would allow the city to start approving retail dispensary licenses, shops could start showing up more in other neighborhoods. Escudero said adding one or two more dispensaries could impact a neighborhood's ranking on the list. The city will recalculate this list annually.

Another possible change would redefine the 1,000-foot buffers by measuring them from a building instead of a property line. Escudero said this will open up a bit more space. He said this proposal was a compromise reached between the department and people involved in the industry who provided their feedback for the proposed rules.

In addition to the headline-ready changes like allowing weed delivery and weed consumption on-site, the proposed laws will only allow so-called social equity applicants to apply for licenses for new recreational shops and cultivation locations. People who fall under this category include those who were arrested, convicted or were subject to a civil asset forfeiture connected to a marijuana offense (the definition for who falls under this category comes from a state bill passed in 2020.)