Margarita Hernandez said she felt fine after the shot. Staff at the Barnum Rec Center in Denver's Westside gave her her first COVID-19 vaccine while she stayed in her car, sunshine glaring on her face. The situation was ideal for Hernandez, who has hip issues that make moving difficult.

Hernandez learned about the rec center, one of Denver's five community sites meant to provide vaccines in the city's most underserved areas, through her daughter, Ana Maximiliano. Maximiliano learned about the site from a flyer she saw at Force Elementary School, where her children go to school.

The two live in southeast Denver. They originally tried to get a shot at a different community site, in Harvey Park South, but were told to visit Barnum instead because the Harvey Park location had run out of vaccines that day. Maximiliano, who speaks English and Spanish, made the appointment in English. Her mother only speaks Spanish.

"I was asked if this recreational center wasn't too far, and I told him that it wasn't too far, so he told me, 'OK, you can take your mother there to get a vaccine,'" Maximiliano said in Spanish. "What worried me most was my mother."

Maximiliano has witnessed firsthand what the disease is capable of. Her father, Jose Maximiliano, died of COVID-19 on November 22. She remembers the day and time it happened: a Sunday, around 9 in the morning.

"We never thought he would die from this," Maximiliano said. "His lungs couldn't provide more oxygen."

The community sites are supposed to chip away at the inequitable distribution of the life-saving COVID-19 vaccines, which have mostly gone to white and wealthier people in Denver.

"Now, we're doing everything we can to ensure equitable access to the still-limited amount of vaccines, particularly in our African-American and Latino communities," Mayor Michael Hancock said March 4 when he announced that more community vaccine sites were opening. "That's the goal of our city-based sites."

But data show that despite efforts from the city and other local organizations, Latinos are still being vaccinated much less frequently than their white neighbors, including at the community sites.

According to data compiled by Denver Public Health, Latinos comprise only 13 percent of city residents who have gotten an initial shot, compared to 72 percent of white residents (the race and/or ethnicity of at least 12 percent of people who got their first vaccine is unknown). Meanwhile, Latinos make up 48 percent of COVID-19 cases in the city and 30 percent of the city's overall population.

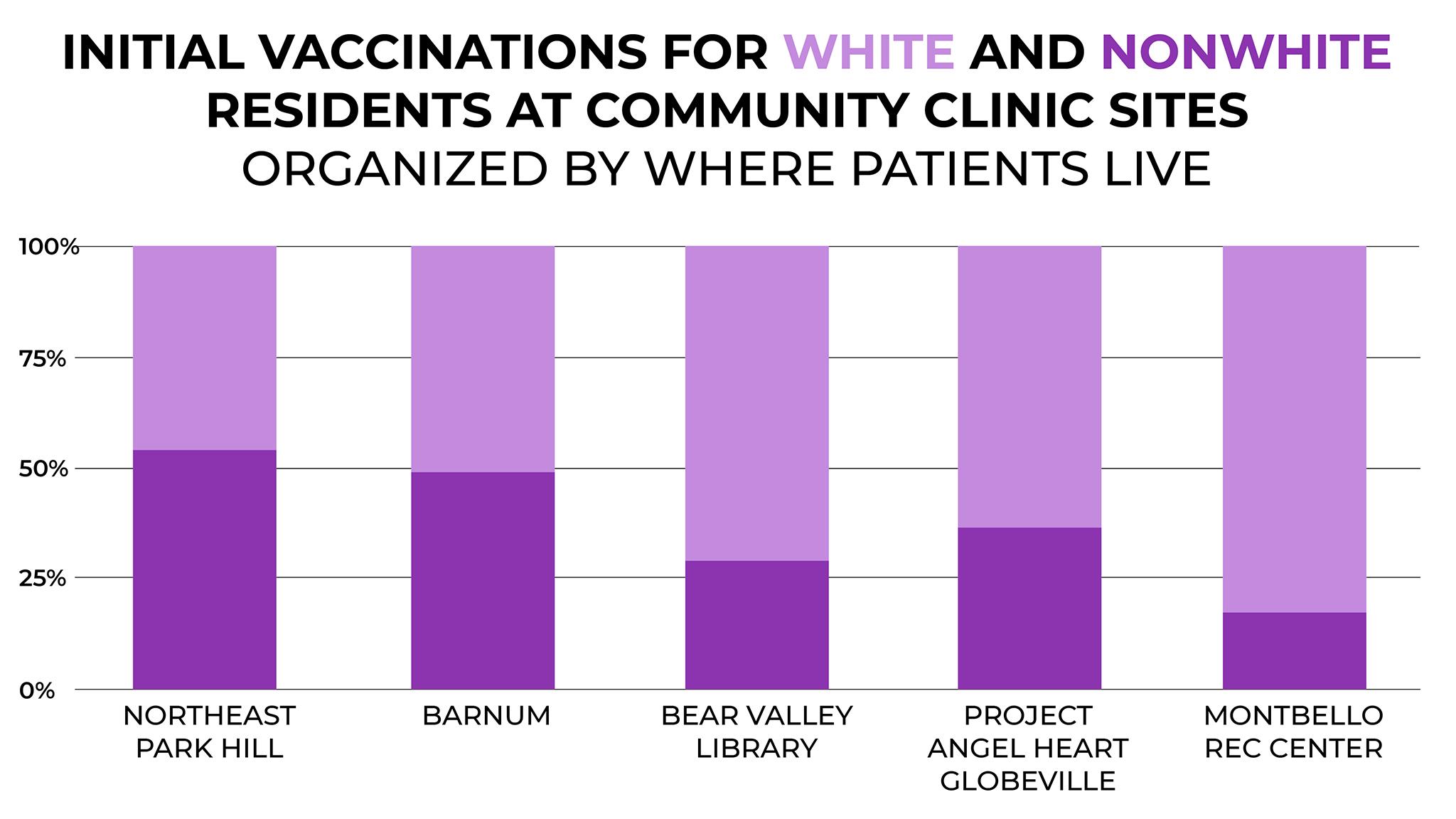

Data provided to Denverite shows the community sites vaccinate more white residents than Asians, Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans or Pacific Islanders.

In addition to Barnum and Harvey Park South, there are vaccine sties in Globeville, Montbello and Northeast Park Hill, neighborhoods with relatively low vaccination rates. The five community sites offer about 200 shots once a week, according to city spokesperson Loa Esquilín García.

Esquilín Garcia said the city is aware that the sites are not vaccinating enough Latinos. She said Denver is changing its strategy now that it has more data and information. For example, the city has started offering rides to the sites after transportation was found to be a barrier to getting vaccines. Esquilín Garcia said the city is looking to expand capacity at the community sites by offering more shots on more days of the week.

Experts attribute lower vaccination rates among Latinos to a few things. Many work hourly jobs that make accommodating vaccine appointments during the day difficult. They also face language barriers and the difficult sign-up process.

Dr. Sarah Rowan supervises COVID-19 testing for Denver Health. Rowan, who has a few titles at the hospital, including associate director of HIV and viral hepatitis prevention, has noticed that fewer Latinos are being vaccinated by the hospital, as well.

"In fact, over the last month, the gap between the percentage of the white population versus Latino population has actually widened," Rowan said. "So it seems like the disparities are getting worse in some ways."

She said signing up for a vaccine can be difficult because of poor customer service by providers. And while going online and finding an appointment sounds simple enough, the system isn't easy or convenient for people who aren't computer savvy.

Neither the state nor the city track data on the race of essential workers, but a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that more Latinos reported working in essential industries (68 percent) than non-Latinos (60 percent) and that Latinos in Denver disproportionately work in industries that are more at risk for coronavirus exposure, including agriculture, construction, health care, food services and waste management. A state law passed last year requires employers to provide COVID-related leave, including for things like vaccines.

Patricia Robles works for SEIU Local 105's member resource hotline, answering calls for janitors in the union about vaccine access. The union also represents health care workers, security offers and DIA employees.

Robles has worked as a janitor for nearly three decades. Now, she fields calls in Spanish from people who need help finding an appointment or who have questions about the vaccine's efficiency or whether it will make them sick, a big deal in industries where missing a day of work could end up affecting someone's ability to pay bills, Robles said.

"Some people call and say they don't have health insurance, so how will they get one? Others call asking about much it will cost," Robles said in Spanish. (The vaccine is free, and you don't need to have health insurance to get it.)

She suggested the state set up a phone line in Spanish for people to call in with questions. To help inoculate more people, the union is partnering with one of its local janitorial contractors for a vaccination clinic on Friday.

When asked by a Spanish-speaking reporter during a press conference last week about the strategies Colorado is deploying to improve vaccination rates among Latinos, Gov. Jared Polis said the state is working with organizations with established community relationships, though he declined to name any, to organize vaccine clinics.

"For us, it's important we vaccinate all Coloradans," Polis said in Spanish. He added that people don't need to be citizens to get vaccinated.

Nearby New Mexico is showing Colorado up. The Land of Enchantment -- which has the largest share of Latinos of any state -- is second overall in vaccination rates in the country.

It's achieved this through "a combination of homegrown technological expertise" and "cooperation between state and local agencies," according to the New York Times. The newspaper reported authorities there made vaccines available in "roughly equal proportions across the state" from the start of the rollout and created a centralized portal for people to sign up for a vaccine.

In March, officials in California, another state with a large Latino population, said the state would dedicate 40 percent of available COVID-19 vaccines to residents in the most underserved areas. Still, Black and Latino residents lag behind white and Asian residents in getting the vaccine.

Rowan said Denver's community sites and others like them are important in the fight against COVID-19. But they need to provide more dosages more frequently to be more effective in addressing disparity.

"They're all really important, but they're just kind a drop in the bucket to what's needed," Rowan said.