Tomorrow morning while most of Denver sleeps, light will strike the Daniels and Fisher Tower, memorializing the birth of the atom bomb.

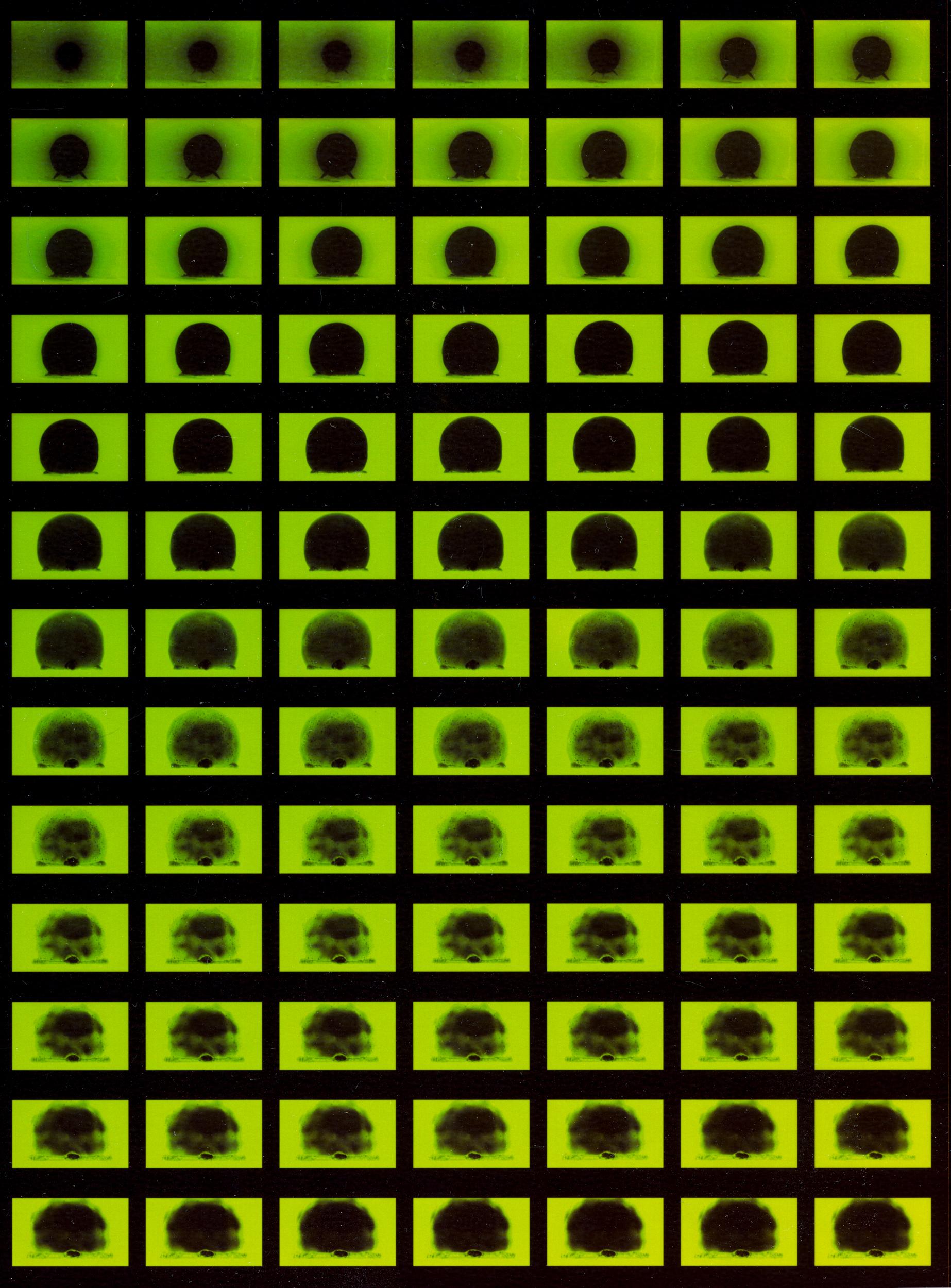

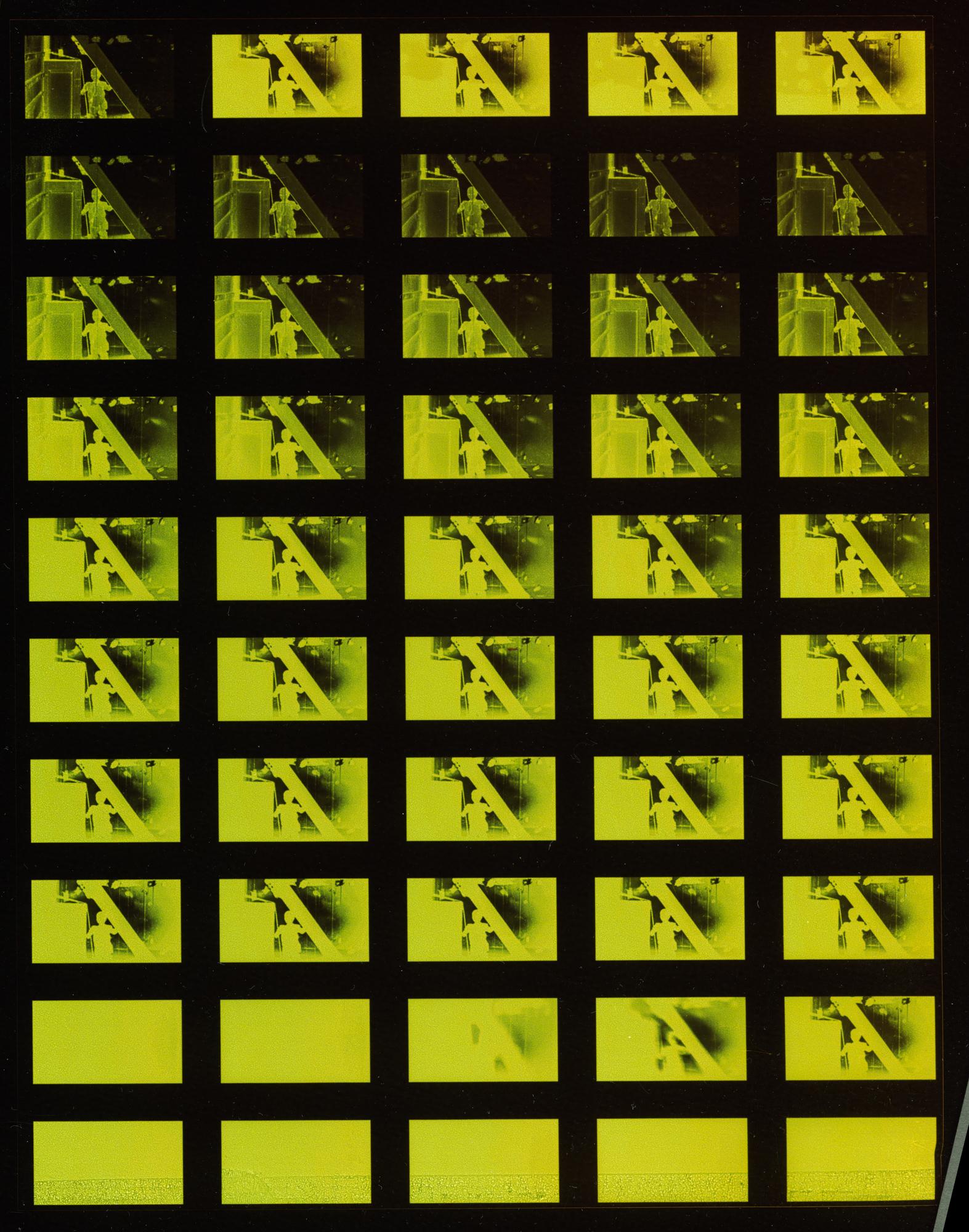

Projected neon green light will wash over the tower, showing an explosion in reverse: a mushroom cloud contracting, and the bomb's victims -- mannequins, houses, vehicles -- reconstructing, returning to their prior state and to a pre-nuclear world.

The project, a video called Aborning New Light by Japan-born and Baltimore-based artist Kei Ito, is a reconstruction of archival government nuclear testing footage, edited to show the bomb testing in reverse. It's a collaboration with Night Lights Denver, which projects large scale works of art downtown, and The Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins.

"There's this idea that art is for certain people and it's in certain places, and I love art for everybody," said Hamidah Glasgow, executive director and curator of The Center for Fine Art Photography. "Especially work like Kei's that has such deep meaning, but also works on the surface level. To have that in public space is so important. And to meet people where they are with it, I think, is so important."

While a shorter version of the video will play on the tower for the rest of the month, the full version will play only at 5:29 a.m., July 16 -- the exact timing of the first ever nuclear explosion, a testing by the Manhattan Project in New Mexico 76 years ago.

"Before that moment, nuclear weapons didn't exist. It was only the theory," Ito said. "Reversing the footage I have in the video really represents me desperately trying to wind back the clock."

By telling the story of the past, Ito hopes to encourage people not to make the same mistakes. He said that practice of examining the past to imagine a nuclear-free future runs in his very blood.

Ito is a third-generation atomic bomb victim, a "hibakusha"-- someone directly impacted by the bombings in Japan. His grandfather, Takeshi Ito, was a Hiroshima survivor who saw the explosion with his own eyes as a high school student. Ito said his grandfather's sister was vaporized near ground zero, and that he lost many more family members to the bomb, either from the blast itself or from cancer from the radiation. Takeshi devoted his life to anti-nuclear activism, traveling the world to share his first-person account of the bomb and the trauma he experienced. Ito said Takeshi worked to spread awareness and gain public recognition of radiation sickness in Japan, advocating for the government to establish a health care system specifically designed for atomic bomb victims. Takeshi eventually died of cancer when Ito was 9 years old.

Now, Ito lives and works in Baltimore, examining through his art both his own nuclear heritage and that of the United States.

"Living in the United States as an immigrant kind of made me think a lot about, 'What does it mean for me to be in the United States?' " he said.

Years back, while completing a residency at the University of Utah, Ito discovered that the library there had a "Downwinder Archive," a collection dedicated to "downwinders," Americans who were exposed to radiation during nuclear testing during the mid 1900s. Colorado is considered a downwinder state.

While Ito poured over the archives, it struck him that the impact of the bomb reverberates across time, spanning and the whole world and multiple generations.

"These people are still alive, dying off because of the cancer," Ito said. "Knowing that this nuclear issue is not contained in Japan, but almost worldwide, including Russia, Chernobyl, and all of the nuclear trauma that exists within the world, I wanted to essentially explore the nuclear trauma of America."

Ito is interested in the invisible.

Through his art, he engages with the invisible threat of future bombings, the invisible threat of downwind radiation and the lingering possibility that genetic mutations from radiation exposure might be handed down across from generation to generation. He said there's some debate about this.

"Not knowing is more scary than anything else," he said. "This idea that I might be affected is scary. Tremendously. But also, this is my artistic journey to figure out, and how to come to terms with it. It's part of my practice."

Another invisible thing Ito is trying to capture: trauma.

"One thing I would definitely say I inherited is the nuclear trauma," Ito said. "You know, witnessing my grandfather passing away, his struggle with the cancer. And through my research, meeting so many people who are suffering, and reading the second-hand stories."

Ito doesn't remember much about his grandfather. Most of what he knows about him he learned in the books his grandfather wrote, or by interviewing his grandfather's friends.

"One thing I remember was him telling me that it was like hundreds of suns lighting up the sky when the bomb exploded," Ito said. "That statement hounded me, and eventually made me become a photographer who doesn't use cameras. I got rid of the camera, because how do I capture something that's invisible?"

Now, Ito is a "camera-less photographer." Earlier in his career, he experimented with taking darkroom paper -- a very light-sensitive paper -- and exposing it to sunlight for short bursts, timed with his own breath.

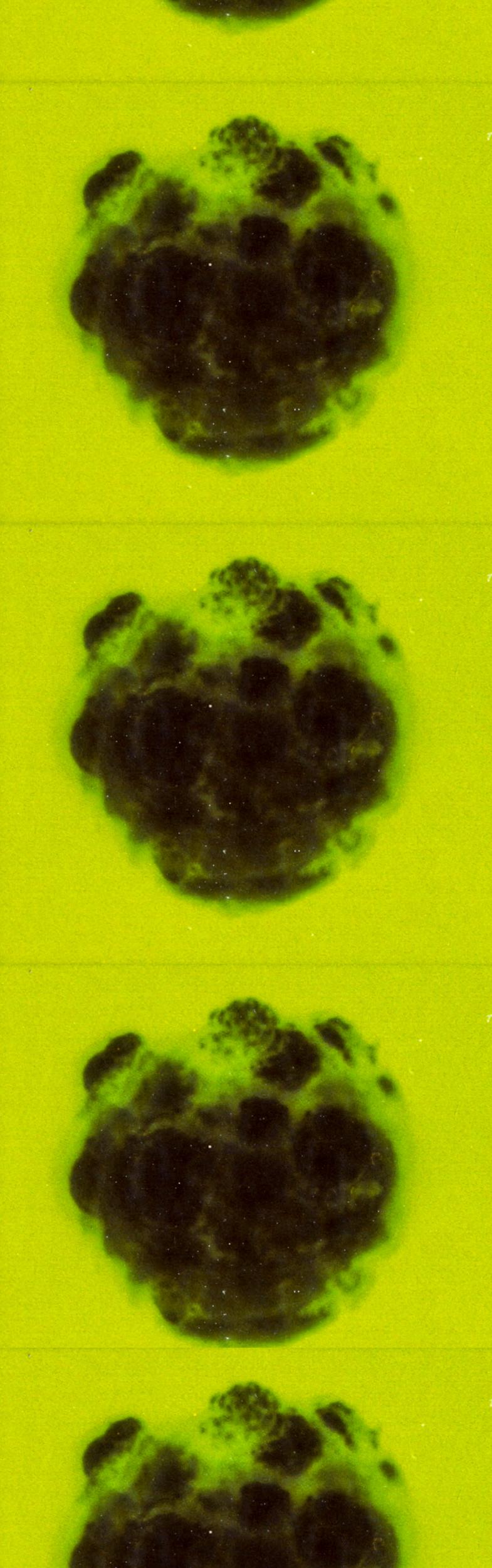

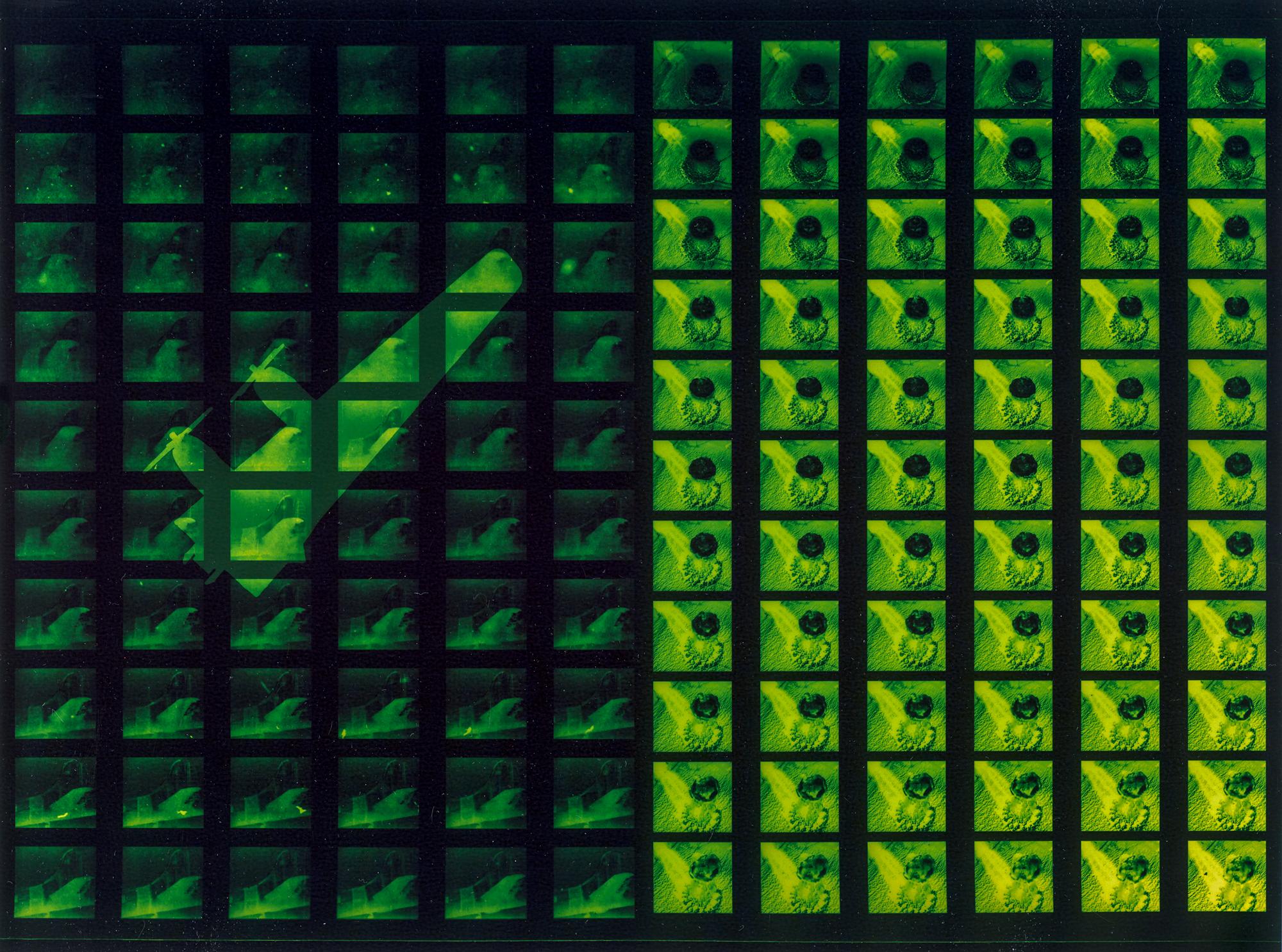

In typical film photography, you'd sit in a darkroom and place film into an enlarger, which you'd use to print the images onto darkroom paper. For "Aborning New Light," Ito gathered declassified government footage of nuclear testing and converted dozens of frames into "transparencies." He placed the transparencies on top of darkroom paper and then, in short bursts, exposed them to sunlight. He then rescanned the prints so the colors became inverted.

"This footage is re-exposed with, essentially, the trauma that I inherited. Which is the sunlight," Ito said.

Ito originally created the piece as a collaboration with sound artist Andrew Paul Keiper. The version you'll see on the tower in Denver is re-edited to fit its new frame, and silent. Ito said when he learned his Night Lights piece would play in July, he wanted to create a version to time with the anniversary of the birth of the first ever atom bomb.

"Which is essentially the origin of who I am," Ito said. "Obviously, I was born in Japan, but I always considered New Mexico as my second home. Without these testings, I wouldn't be who I am, and I wouldn't exist. "

Ito said that as an artist, his role isn't to cast blame.

He said he exists not in the black and white but in a sort of limbo, or liminal space, of trying to understand. While Ito believes the bomb and war themselves are evil, he can't determine whether any person or party is evil.

"If that's the case, I wouldn't be making work about America," he said. "I'm myself trying to figure out the trauma as a whole, not just about Japanese Americans. It's a global issue that could happen any time."

When Ito was studying art at MICA in Baltimore, he met his now collaborator Keiper. They became good friends. When Ito began his work exploring nuclear trauma, Keiper initially was pretty quiet about it.

One night, when Ito mentioned he had a grandfather who'd survived the bombing in Hiroshima, Keiper explained that his grandfather had been a Manhattan Project engineer, who'd helped to develop the bomb. But Ito said there was no ill will between them.

"If anything, it bonded us together stronger," Ito said. He said they're still best friends, and that Keiper was even the best man in Ito's wedding. And they started making art together about the United States' nuclear heritage. Ito created the visuals, Keiper the sound.

"We think of our work as trying to find a mutual ground, not just for us, but for other people," Ito said.

Ito said he makes his artwork in part to warn today's world about the threat of nuclear bombs. He said people became more aware of the threat after tensions rose between North Korea and the U.S. during Trump's presidential term.

"Remembering the history is the one thing," he said. "But it's still a relevant issue that we face today. And the only way to prevent this is to learn from yesterday's trauma."

He mentioned the Doomsday Clock, a calculation of how close we are to man-made global catastrophe, as determined by a group of world-renowned scientists. The aim is to calculate how far we are from "midnight." Every couple of years, the group adjusts the dial on the clock.

Right now, the time is 100 seconds to midnight.

Some view the bomb as a sacrifice to end the war, to create peace. Ito said that the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were victims of that goal. So, too, are downwinders.

"It always requires sacrifice to achieve the peace where we stand right now," Ito said. But he said it's not a choice nuclear victims made. It's a choice someone else made. Ito said the bomb could happen anywhere, to anyone, and without much warning.

"The thing about sacrifice is it needs to be sacrificed so many times," Ito said. "Are we, as today's people, going to be possibly the sacrifice for the next great peace?"

Ito said he's glad the projection is in an accessible location, projected on a tower downtown where anyone might see it.

It even recalled for him stories about people flocking to nuclear testing sites to watch the explosions during the Cold War. It was a spectacle of light.

"People would pack a lunch or dinner and go out to the field and observe. There's many photographs of people just watching, eating, with the baby in hand," he said. "People are witnessing this nuclear light without thinking about consequence."

Similarly, when people view Ito's film, they will be watching a spectacle of light. He hopes that this time, though, viewing the art might help them consider the consequences of nuclear war as they watch the bomb explode in reverse, and imagine a world in which that first bomb did not drop.

When the film plays Friday morning, most Denverites won't know about it. Some will stumble upon it. Others will sleep through it, completely unaware of the simulated explosion striking the 16th Street Mall. Glasgow, with The Center for Fine Art Photography, said whether people get up to see the film does, and doesn't, matter.

"In some ways, if nobody's there, or very few people are there, it's replicating what happened when that first bomb was tested," Glasgow said. "It happened, and whether or not we knew about it or not, it changed the world that we live in."

Aborning New Light will play at 5:29 a.m. July 16 on the Daniels and Fisher Tower on Arapahoe and 16th. A shorter version can be viewed for the full month of July 2021