Panaderia Rosales is one of those businesses that has the power to take people back in time.

The bakery, located just a few blocks from Denver's North High School, is lined by glass-fronted cases stacked with trays of sweets. An antique Dr. Pepper machine stands by the door. Racks of dried spices, bagged snacks and miscellaneous kitchen gear line one wall.

And as they enter, many guests have a story to share about the pastries that have kept them coming back for decades -- conchas, gingerbread and sweet empanadas.

"My favorite snack is the sprinkled cookies, the rainbow cookie -- but really you cannot go wrong with anything in this place," said customer Carina Batres.

For Batres, who grew up in northwest Denver before moving to Westminster, the bakery is a touchstone in a neighborhood that has developed and gentrified more dramatically than almost any in the state.

"The neighborhood has changed so much. It's nice to have something familiar," she said.

Today, Panaderia Rosales sits near a coworking space, a brewery and lots of new condo builds -- all the common signifiers of gentrification. And as the area has become more affluent, it has also become a lot more white.

In the past decade some neighborhoods of northwest Denver have seen a double-digit decrease in the percentage of their population that identifies as Hispanic their Latino populations, according to the final census numbers.

With that change comes questions about the future of a neighborhood that has been a center not just of Latino culture but also of the Chicano political movement.

When the Rosales family opened their bakery almost fifty years ago, the neighborhood they were serving was almost three-quarters Latino. Their grandson, Javier Rosales, grew up in the apartment above the shop -- and he remembers watching the neighborhood below as it grew into a Latino political force.

"I was actually a little guy, looking out the window," Rosales recalled. "And this big group of people (came) marching down 32nd avenue. They had Corky (Gonzales), they had (Paul) Sandoval... I watched pretty much the Chicano movement walk down 32nd to downtown.

Gonzales and Sandoval helped lead a movement that fought against inequities and racism, especially in education. Their activism also helped usher in an era of Latino political representation on the Northside.

"We started sending people to the statehouse -- Latinos from this neighborhood," said Rosemary Rodriguez, who was active in the protest movement and went on to serve as Denver's clerk and recorder. "They became lifetime leaders from the community."

Today Denver's north and west sides are almost entirely represented by Latino elected officials; more than a half dozen serving in city and state government. But some longtimers wonder if that can last.

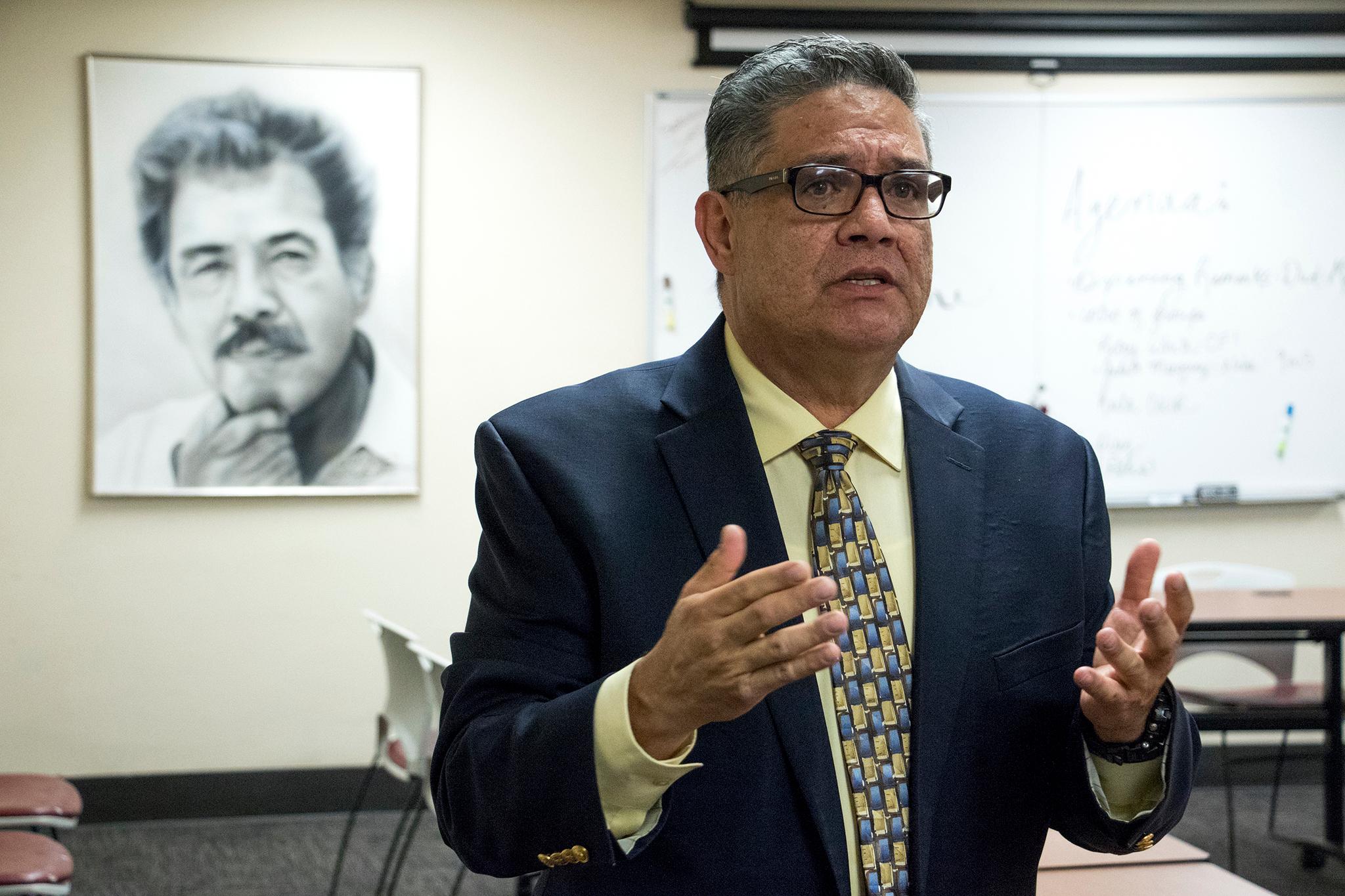

"If the kids aren't going to stay there, you can't convince them to stay there if they want to sell, because it's a windfall for them. You know, it's their prerogative," said Rudy Gonzales, son of Corky Gonzales and head of the statewide nonprofit, Servicios De La Raza. "But that will hurt us in terms of having representation there in Northwest Denver."

So far the change hasn't played out in the area's politics, which are overwhelmingly Democratic.

In 2018, when the four state House and Senate seats that represent this part of town came open because of term limits, each race had only one person of color in its Democratic primary, according to state Senator Julie Gonzales.

But all of them won.

"And so to see all of us emerge as the Democratic nominees for the seats was really affirming of the fact that the community wanted to see... leadership emerge from Denver that was reflective of the diversity of Colorado," said Gonzales.

A new map could have a big impact on who eventually replaces Gonzales and others as elected leaders representing this part of Denver.

When Colorado's redistricting commission released its draft state House and Senate maps earlier this summer, Latino political leaders quickly raised concerns about where the lines would fall in northwest Denver.

For example, the state Senate district for northwest Denver, District 34, could see its Hispanic-identifying population drop by roughly 20 percentage points -- from about 45 percent to 24 percent. That's because the district could lose some of its most heavily Latino neighborhoods. (An adjacent district in southwest Denver, meanwhile, would gain Latino votes.)

"To have less than 30 percent of a historically Latino population, it's going to change the policies that you bring forward because the policies come from the people," said Amanda Sandoval, who represents the area on Denver's city council. Her father, Paul Sandoval, was one of the first Latinos elected to the Colorado legislature.

Sandoval said she tries to ensure that newcomers in her constituency understand the neighborhood's historic identity, and the importance of reflecting that in its representation.

State lawmakers have generally been reticent about weighing in on how the redistricting process could affect their own seats. But Gonzales acknowledged she's concerned.

"I don't know what the magic number is," she said about ensuring her district contains enough Latino voters to ensure they remain a political force. "That is for the commissioners to decide what the right number is. But I really do hope that they're thoughtful and considerate of Colorado's diversity as they're drawing these maps.

Fourteen of the state's 100 lawmakers are Latino, a historically high number, but still disproportionately low compared to their nearly 22 percent of Colorado's population.

Latino advocacy groups have been some of the most active voices in proposing changes to the commission's draft Congressional and statehouse maps. CLLARO, the Colorado Latino Leadership, Research and Advocacy Organization, recently put forth a radically different Congressional proposal -- it would create a southern Colorado-based district to maximize representation for the region's historic Hispano communities, as well as a 40 percent Latino district in the Denver area.

At a press conference in Denver's Lincoln La Alma park to unveil the group's plans, Executive Director Mike Cortes said: "It's critically important that the outcomes of our redistricting process reflect the varied and distinctive nature of our Latino communities, considering each of them within their own context and ensuring that our voices are appropriately represented to our state elected officials."

For state House and Senate seats, moving a boundary line just a block or two in densely populated Denver can have a big impact on a district's makeup. And while the new process aims to reduce the influence of politicians on the lines, some Latino leaders worry commissioners lack the on-the-ground understanding of neighborhoods and communities that comes from political activities like campaigning.

There are "twelve commissioners on each of the two commissions who intentionally have not been actively involved in this aspect of politics. And so they are truly drinking from a fire hose," said state Rep. Adrienne Benavidez, whose Adams County district skims the northern borders of Denver. Currently, more than half her constituents are Latino.

Benavidez wants the commission not just to preserve the voting power of long-standing communities, but also to think about where Latinos priced out of Denver are resettling.

"People stay together," she said. "If they have been priced out of Denver or can't keep their homes, they move to Adams County or Lakewood, a little bit to Aurora, but... the community stays together wherever they are."

Now, more people are finding community in Adams County.

When she was a teenager living in Commerce City, Theresa Bustos Ortega hitchhiked to join Chicano demonstrations in other cities, like Boulder -- "because that's where all the action was."

Over the years, she's also seen the neighborhood here change, becoming more heavily Latino. She can track the difference in the colors people chose to paint their houses, and the arrival of new restaurants and groceries that carry products from Mexico and Central America.

While many of the city's new residents are recent arrivals in the U.S., compared to her family's deep roots in northern New Mexico, Ortega believes they share many political concerns.

As a first-generation college student who now works on the CU Library staff, Ortega said the community here has a shared interest in fighting for better education.

But she also recognizes there's still a lot of work to do to get people politically active, especially while many in the community are struggling just to keep food on the table.

"I think the problem with Hispanics not getting into politics is we're just surviving," she said. But, "I see the powerhouse growing and I can't wait. I'm just happy."

Adams County has been growing overall; its population increased nearly 18 percent in the last decade, according to the new census numbers. It's also started electing a new generation of Latino leaders to local and state government. In addition to Benavidez, Commerce City is represented in the state senate by Sen. Dominick Moreno, who sits on the powerful budget committee.

Still, at-large city councilman Jose Guardiola said he hesitated before running for office.

"One of the thoughts was like, man, my name is straight Mexican, right? Jose Guardiola. Who's going to say that name?" he said recently. "But then I remember my culture and my pride and like, well, they're going to have to learn it."

Guardiola was born in Wyoming to parents who grew up in Mexico. He considers himself Chicano and got into politics, in part, to represent the diversity within the Latino population. But the spread-out suburb presents challenges that leaders on Denver's dense northside don't face.

"People have different needs and wants and to organize in such a vast area is a lot harder," he said.

And if Latino populations are getting more dispersed as they move out of the city, it also puts them more at risk of having their votes diluted into a bunch of majority white districts. It's something Latino leaders hope to combat with their robust lobbying effort toward the redistricting commission, as they try to help commissioners see the borders of communities that aren't set down on any official map.

Enjoyed reading this story? You can also listen to more tales about the redrawing of our state and what it means for Coloradans with our politics podcast, Purplish. Search for it wherever you get your podcasts, or find all the episodes here.