Civic Center, in its roughly 130 years of existence, has never been shut down the way it was last week.

Low-slung metal barriers now cordon off the entire park, including MacIntosh Plaza in front of the Webb Building and Pioneer Monument fountain to the northeast. Most of the people experiencing homelessness moved to nearby blocks or settled behind Denver Public Library. More temporary structures now spill toward the Denver Art Museum.

The city cited a long list of reasons leading up to the Sept. 15 closure, including litter, rotting food, dozens of rodent burrows, human and pet waste and improperly discarded needles. So what now?

Civic Center Park, the green anchor between the State Capitol and City and County Building, adjacent to the Denver Art Museum and the Denver Public Library -- a place that some in the city have spent considerable effort trying to prep to draw substantially more people on a more regular basis -- is now closed indefinitely.

"A civic space, by definition, is for the use of all, and when when not all are welcome, there will be some voids that are created," Ignacio Correa-Ortiz, a Denver architect and urban designer, said. "The people who are currently inhabiting the space are there because there was a void that was not filled."

A look at the park's history shows the void has been there, in different forms, for decades. But the park was created with grand visions in mind, and with high hopes for the future.

Even before its completion, Denver newspapers were initially quite reverential to the site. A Denver Post article published in 1928 described the park as a "magnificent dream of the old world transplanted into the newest of cities," and compared it to monuments in Rome, Paris and Vienna.

The Civic Center has also been the venue for public discussion since its inception. As early as 1920, an article from The Rocky Mountain News proclaimed that Civic Center's open forums would permit "discussion of any subject under the sun." The only topics not permitted were "theological questions" about the end of the world.

Now that the park is closed, major civic engagements, like the 2021 installment of the now-annual Women's March originally slated for Oct. 2, will have to be re-homed.

And creating a timeline for reopening is virtually impossible -- the regeneration and growth cycle of the turf being reseeded will be unpredictable, as will the efforts to contain the quickly-reproducing rodent population. Denver Parks and Recreation will also take the opportunity to trim trees, upgrade irrigation and install new LED lights while the park is closed.

The city's comments on reopening have been sparse. A city press release said the park would open "when work is complete and all public health issues have been mitigated."

The park is currently under the charge of the Civic Center Park Conservancy, a nonprofit founded in 2004 alongside a new master plan -- a plan that laid the groundwork for things like the judicial buildings that were built to the east of the park and Daniel Libeskind's ultra-modern addition to the Denver Art Museum. The conservancy also supports upkeep by raising money for restorations and subsidizing the costs of improvements. A big ask, since funding has been one of the biggest barriers to improving the park.

The Conservancy's most recent major planning process, called the Civic Center Next 100, outlines the park's next moves. Unlike previous planning processes in the '80s and '00s, the Civic Center Next 100 is not pushing massively-ambitious projects like, say, putting Colfax underground in a tunnel, building a giant reflection pool or creating a 330-foot tower in the center (all real proposals!).

The Civic Center Next 100's goals are comparatively pragmatic and without extravagant budgets.

The improvements currently up for public comment include upgrading the Greek Amphitheater with new features for staging big shows, creating a new central gathering place in the park and adding pedestrian amenities to Bannock Street, which has already been blocked from car traffic. The earliest improvements to the Greek Amphitheater could be visible by 2025, but it's all up to whether the conservancy can cobble together enough public and private funding sources.

But despite the Conservancy's partnership with the city, the government shutdown largely kept the organization in the dark leading up to the closures, the Conservancy told Denverite.

It's no secret Civic Center Park has not felt particularly beautiful or inviting for some time now.

"We've seen cycles in Civic Center where things get more challenging, and we're in certainly one of those challenging periods right now," Conservancy Director Eric Lazzari said. "As somebody that's been in the park producing programming for 10 years -- this summer, it's felt different."

We spent time with 100 years' worth of news clippings, magazine articles and public records looking for a precedent for this closure -- and came up empty-handed. The pages we read paint a picture of a park shifting between phases of regular use and overuse, real and imagined crime surges, and cycles of abandonment and revitalization.

The park's early days were seemingly peaceful. A Rocky Mountain News Article from May 1947 described the scourge of residents plucking tulips from the Civic Center's gardens. The city responded by imposing fines.

In 1967, another Rocky Mountain News writer lamented that that no one used Civic Center except for a "small group of elderly men" and "a few hippies." A common thread begins here -- the park is either described being under-used, or being used by the wrong kind of people. Vague descriptions of transients continue through the present day, raising in pitch during the mid-'00s.

Records from the 1970s still describe an idyllic Civic Center, with residents more fearful of encroaching skyscrapers than anything within the park. In 1972, Duncan Pollock of the Rocky Mountain News wrote, "Were he alive and well today, Mayor Robert Speer would probably smile benevolently on Denver's Civic Center... [it] has become a gateway to the downtown area and a noble symbol of the Mile High City."

A 1978 Denver Post article described a park mostly inhabited by young people who played frisbee and touch football, but sometimes left their "cigarette butts, poptops, and the occasional marijuana roach" on the ground. The same article documented a police crackdown on the "marijuana cigarettes" being sold in the park, largely on the sly.

Denver Vice Detective Tom Fisher described the laid-back nature of the criminals at the time: "A lot of these characters seem to think that having less than an ounce of grass isn't illegal... But in this state, it is, and we have to bust 'em for it." In the article, officers nabbed an airman from Lowry Air Force Base for selling 10 joints to an undercover officer. Drug busts would continue, without shutting the park down, into the '80s.

In a 1985 article, journalist Allen Young said Civic Center was "serving the homeless as a campground and the lonely as a rendezvous spot" for years. Young also accused the park of "just being there," standing mostly empty between big events. Even crime largely avoided the abandoned park.

The city has come close to shutting the park down before. As Denver continued to grow, and as massive events brought people to the city center, officials had to grapple with increased park use. In a 1990 Denver Post article, the city's deputy manager of parks said the Grand Prix followed by A Taste of Colorado was just too much for the turf to handle.

"What we're trying to avoid is that scenario where we have to shut down the park so it has time to recuperate," he said at the time. The park's grass had allegedly turned from "a sea of green" to a "pool of brown" with damage ranging from $4,000 to $10,000 (today, that would be $8,000 to $21,000) by early September.

However, he said the city would be able to rehabilitate the turf in time for Mexican Independence Day revelers to celebrate later that September.

People fought about Civic Center even before it existed.

Civic Center Park, like much of Denver development, had a long and tumultuous public discourse before ground was ever broken. Many early Denverites like Mayor Robert Speer had grand visions for the events, artwork and cultural exhibits the park would represent and host.

The park can trace its earliest beginnings to 1878, when Mayor Richard Sopris created a plan for two city parks connected by a tree-lined boulevard. In 1890, when the State Capitol and its surrounding park were built, more concrete plans for a larger park complex were originated, heavily influenced by the City Beautiful movement and Mayor Speer's vision.

It continued to evolve through 1932, when the City and County building was finished. Between the completion of the two imposing buildings to the east and west, smaller structures like the Carnegie Library from 1909, now known at the McNichols Center, and the Voorhies Memorial and Greek Amphitheater both from 1919, were built.

But Civic Center Park did not go up in a vacuum. An early map of Denver shows that the plots of land where the Carnegie Library and the U.S. Mint stood were flanked by mostly brick buildings and livery stables in 1903. Electric railways ran along Broadway, winding between warehouses and businesses.

Creating the Civic Center meant buying the land and razing these buildings to the ground. There were protests and debates about which blocks to buy, how much to spend and the arduous task of connecting downtown's 45-degree grid with the north-south direction of the rest of the city. Business owners and other influential Denverites quickly began squabbling over the cost of connecting the already-completed statehouse and its 20-acre park to an official Civic Center.

In a 1908 article in The Denver Post, an unnamed businessman feared that the largest civic center plans "would effectually prevent the growth of the business district out Broadway, Acoma and Bannock streets. Nothing should be done to prevent the spread of business."

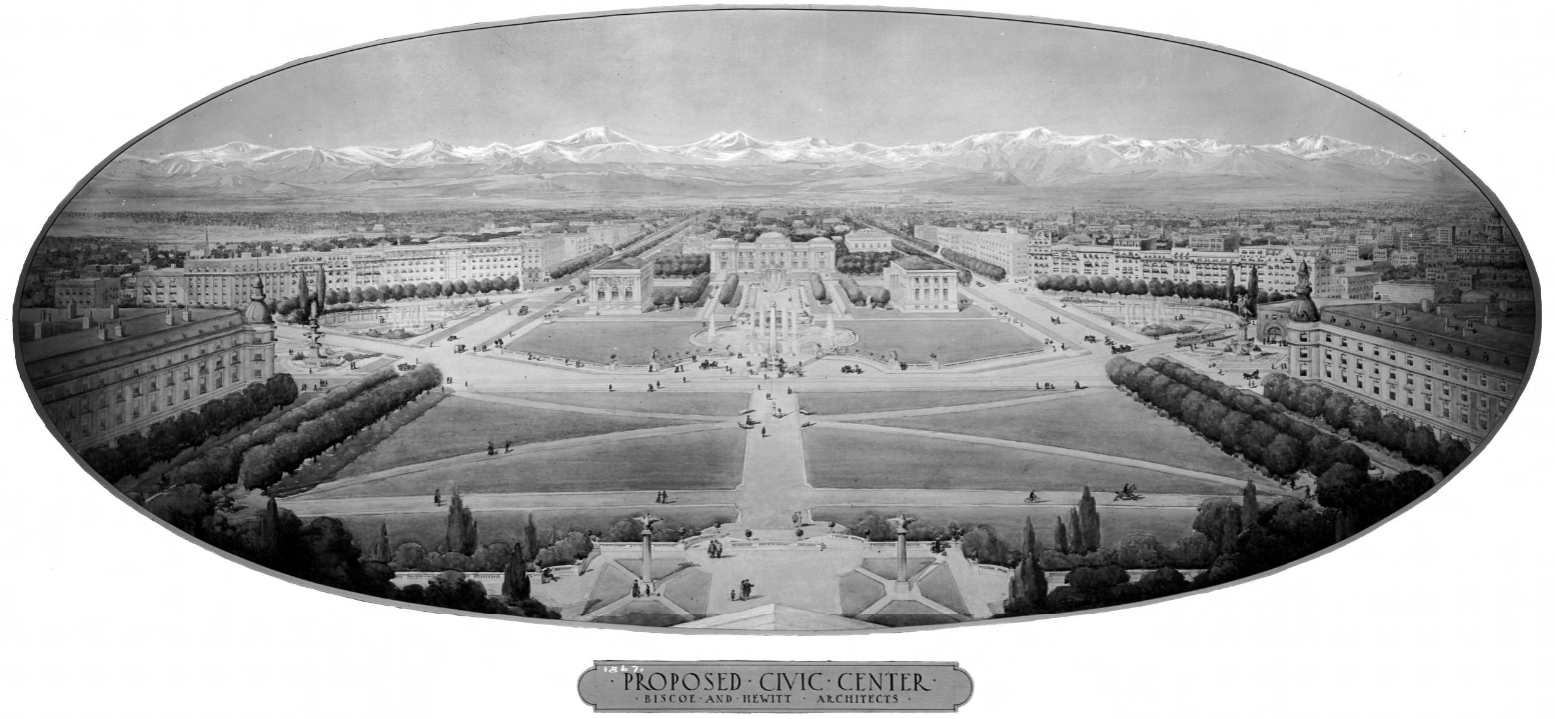

In 1909, the city of Denver voted on beginning land acquisition, and after two years of court battles with opponents, the Colorado Supreme Court allowed the process to begin. The city bought the land it needed for $1.8 million. The drawing below, by sculptor Frederick MacMonnies in 1907, laid out the park much as it is today.

The European-style row homes surrounding the Civic Center and the massive fountain in the center may not be have materialized, but the Voorhies Memorial, Greek Theater, McNichols Center and the City and County building came to be much like the proposal imagined, despite the fact that the final buildings wouldn't begin construction until decades later.

The "civic" part does happen at Civic Center.

This year's Women's March, which is tentatively slated for Oct. 2, will be one of the first events forced to move because of the park's closure. Other events, like the the Rally for Recovery, the Hot Chocolate Run and the Denver Pagan Pride Day will also be affected. And it's still unclear how the Denver Art Museum's grand Oct. 24 reopening might be impacted; The renovations on its north side are directly across from Civic Center Park.

The park is now unable to provide the most visible function it has reliably provided for decades: hosting large gatherings. Notable nationwide movements took root in Denver through speeches and protests at Civic Center Park.

In 1989, Native American activist Russell Means poured blood over a statue honoring Christopher Columbus, calling for an end of Christopher Columbus Day. Means would continue protesting with demonstrations at Civic Center for years to come.

However, it would be almost 30 years before the city adopted Indigenous People's day, and another four years before the statue officially came down -- in 2020 during the George Floyd protests. Those same protests would forcefully remove the park's Civil War memorial statue, which could be replaced by a commemoration of the Sand Creek Massacre.

The day after the inauguration of President Donald J. Trump in 2016, the Women's March on Denver brought thousands of demonstrators to Civic Center. Organizers initially told some news outlets that they believed 60,000 people were present, but by early afternoon, speakers said the crowd had swelled to 200,000.

Denverite was there, and we recorded the stories of some of the people who came.

After George Floyd died in police custody on May 25, 2020 in Minneapolis, thousands turned out again at Civic Center Park to protest police brutality.

People gathered in front of the State Capitol, chanting things like "Black lives matter" and "I can't breathe," then marched through downtown. They eventually encountered police in riot gear who fired pepper bullets and tear gas into the crowds. Later, an investigation would find the police used excessive force in their responses to protesters.

During the closure, fire damage and graffiti to the park's stone structures left over from those protests will be restored and cleaned.

Looking forward, it'll take more than restoring grass to get back to "active and thriving."

There are obviously challenges. Correa-Ortiz says it will still take effort to activate the space when it reopens.

"You cannot have that happen without having the critical mass of people actually using this space, and that comes with density," Correa-Ortiz said. "Our dependency on the automobile and the idea of commuting from home to work by car -- all those things have really created the problem. What we see (at Civic Center Park) is a symptom."

The Civic Center Conservancy's Next 100 plan will continue with its public input process despite the park's closure. The next public workshop on Sept. 23 will allow residents to weigh in on design concepts. It's the last public meeting before the preferred design concepts will be established. But funding is still the deciding factor in whether the projects move forward.

Lazzari, of the Conservancy, said the one thing that hasn't been in question is the community's commitment to the space.

"Whether it was the public outreach that happened in 2005 around the master plan, or the current outreach we have around Civic Center Next 100, or when the park was damaged last summer, in the 4000 people that donated to restoring the park," Lazzari said. "The public has continually told us they love Civic Center."

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the number of years Civic Center Park has been open.