Irma Díaz has been trying to buy a house for about 20 years now.

She said for years, she and her family rented a beautiful three-floor condo. Then, Díaz suffered a back injury, leaving her unable to walk for months and with hospital bills that drained her bank account. Over time she started to recover, but walking up the three floors of her condo was too much for her. She spoke to the building owner about renting another house. The only one available within her budget was a tiny house in Westwood. In order to fit her life into the new space, Díaz said she ended up having to get rid of about half of everything she owned.

"We need a house. We need our own house," she said. "I paid rent for 20, 30 years now. That's a long time. I need my own house."

In a time when housing prices are climbing all over Denver, Díaz and a group of other Westwood women aimed to do whatever it took to buy a home for every member of the group -- in their case, by selling goods like tamales, salsa and zucchini bread.

Visit just about any big Morrison Road event -- Frida Kahlo celebrations, Chile Fest, Veggie Viernes -- and you'll find the Mujeres Emprendedoras Cooperative selling their homecooked goods.

"Mujeres cook the same way that we cook in the house. We don't make the food like in a restaurant," said Matilde García, one of the group's cofounders. That goes for the flavors, but also the portions, which García says are larger than what you'd find in restaurants. Their ambitions are larger, too: Mujeres Emprendedoras intend to fight involuntary displacement in Westwood by building the Mujeres' self esteem, financial skill sets, and sense of self-sufficiency.

"We decided to work with the things that we know how to do," García said. "And one of the things that we do good is cooking." The group began as a catering and food company, and has since expanded to sell jewelry and share resources and knowledge with the community in the hopes of promoting financial independence.

The cooperative formed in 2017, when a group of friends, relatives and neighbors started to notice changes in the neighborhood, as rent and housing prices skyrocketed and developers moved in on the area.

"We started to see a lot of displacement," García said. " She's seen a lot of people move out of the neighborhood in recent years. But she says she knows even more people who choose to move in with other families to save money rather than leave Westwood altogether.

"It feels safe. It feels like a home. And a lot of those people, they worked to change this community, and they don't feel that they want to leave it," García said. "Three families living in the same house is something very normal now."

Housing is limited, and expensive. Díaz, another cofounder, said that though developers are starting to build apartment complexes in the area, it isn't solving the residents' housing problems.

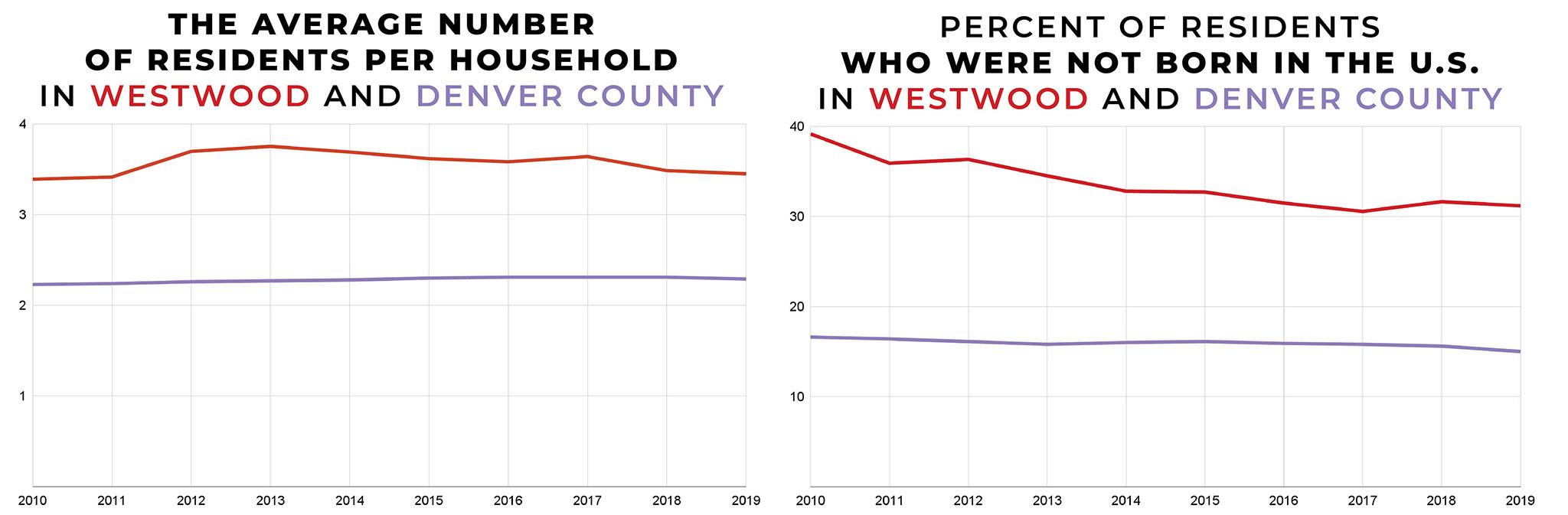

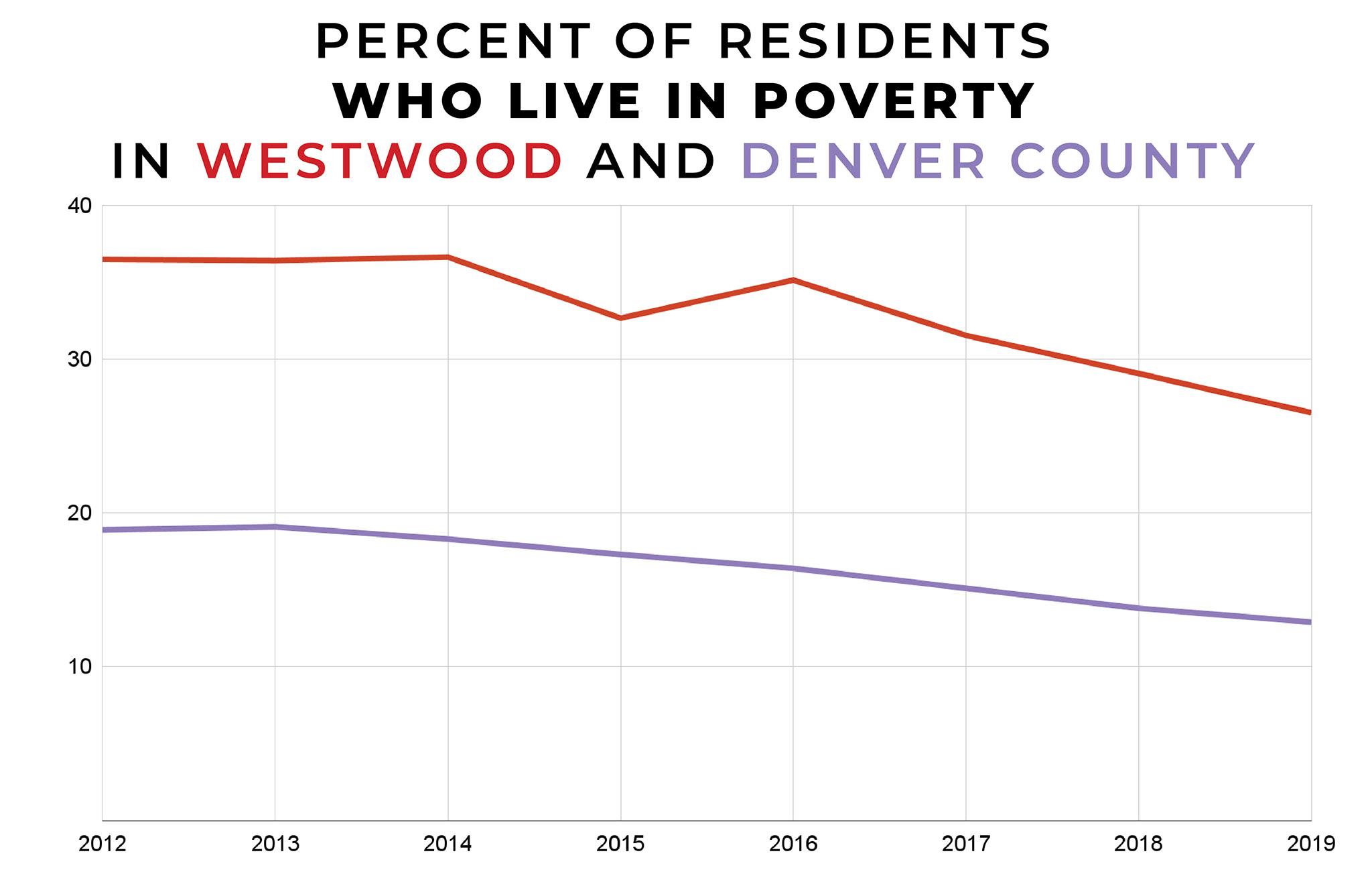

"It's crazy, because the opportunity is not for the neighbors. It's for another person to come and make a business," Díaz said. She said sometimes, developers promise to set up low-income housing, but the units and rates aren't designed with consideration of the people who make up Westwood, which, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau had a higher distribution of immigrants (about 30 percent), larger average household size and higher poverty rate than Denver's average in 2019.

"They say, I'm sorry. The price is very high for you," Díaz said. "You don't have Social. I cannot accept pets. I cannot accept too many kids. Or, this is only for single persons. Too many things."

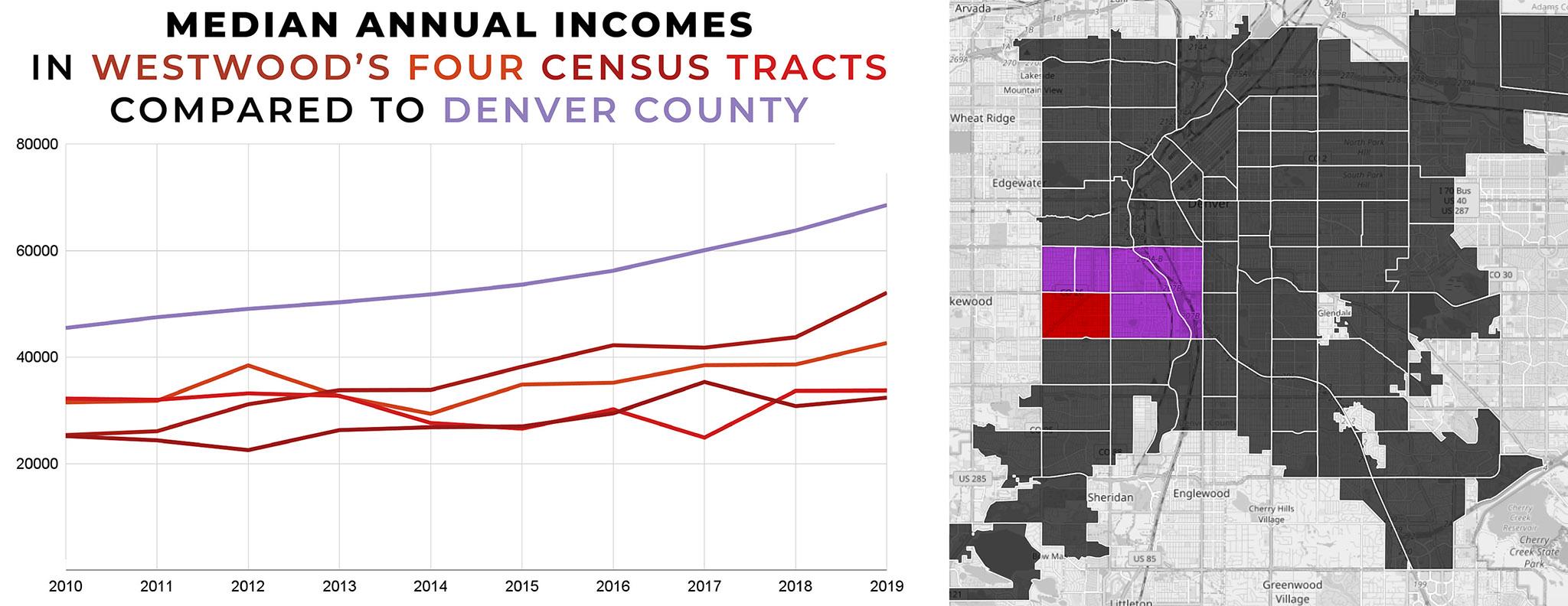

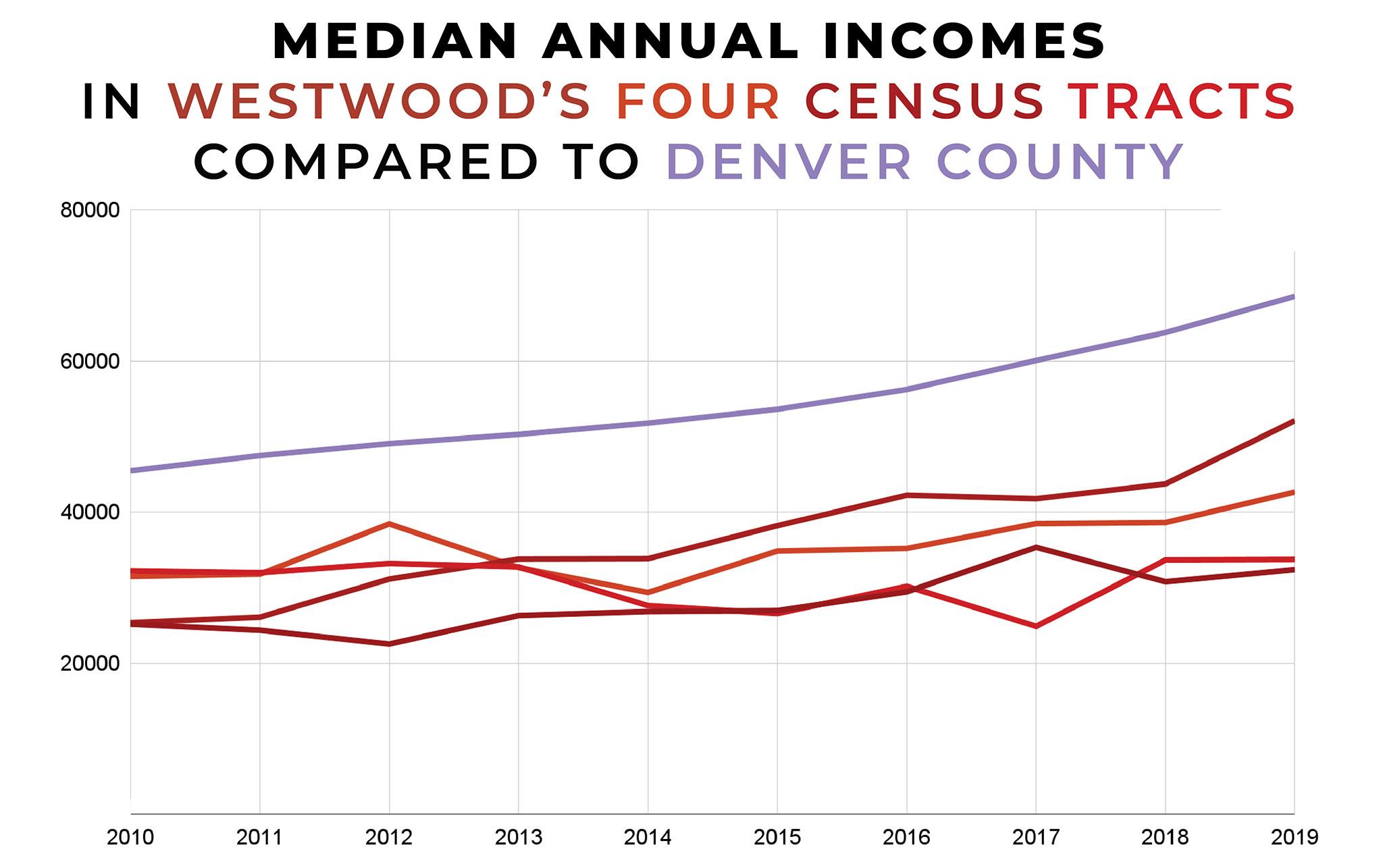

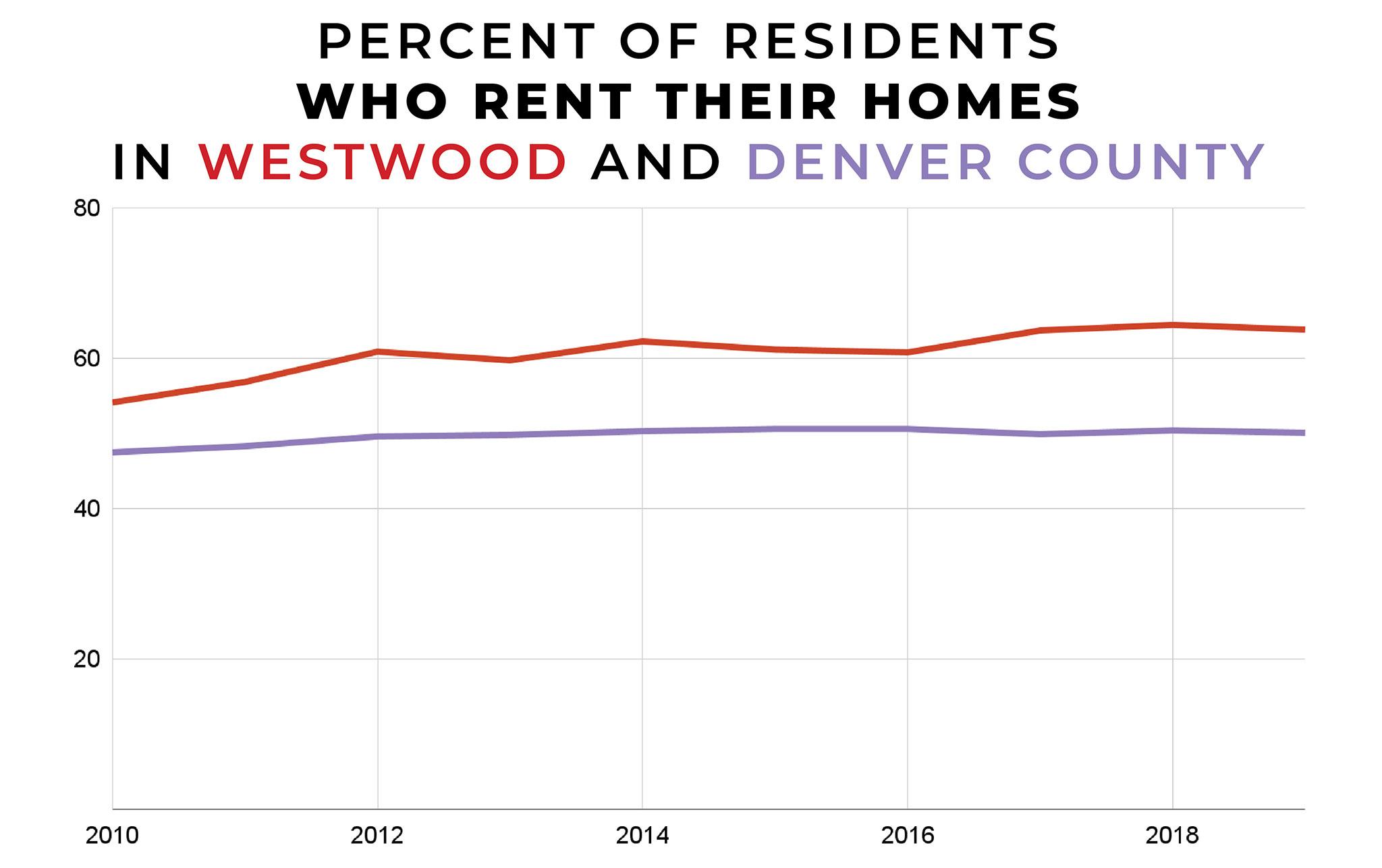

Like in other parts of Denver, Westwood's housing market has seen significant rises in home values in the last ten years. Data from Denver Open Data shows that this year, homes in Westwood sold for a median of close to $350,000 -- more than three times the cost of a home five years ago. While that's not quite as high as the the median closing price for a home in the Denver metro area, Westwood median incomes are close to 60 percent of the overall Denver median income. As housing prices rise in the area, it's getting more and more difficult for the people who've lived there for years to buy property in their own neighborhood.

Of all 13 Mujeres, only García and one other woman own their house. The rest rent.

The group formed with the initial goal of raising money to buy a house for each woman in the co-op.

Each new member contributed a $100 membership fee. They used their first $500 to cover the expenses for their first catering gig in 2017 -- the annual Frida Kahlo celebration on Morrison Road, where they had a table selling zucchini bread and banana bread. They also contribute their skillsets and personal knowledge to the group, but García says its more important that members are committed to building upon their skills.

"For us, it's to give the opportunity to each woman to learn and improve themselves in the way that they want," García said. "The people that become part of the co-op, it doesn't matter if they don't know something. It's more that they want to learn."

The co-op doesn't have a home base. Instead, they work with local community organizations like Re:Vision and BuCu West that allow them to use their kitchen spaces. While the ultimate goal is still to buy each member a house, the group plans to first save enough money to secure their own space to work out of. The idea is that once the co-op has its own kitchen and storefront, they'll be able to make more money, and further their goal of eventually buying a house for every member.

The co-op isn't any of the Mujeres' main source of income. Most of them have jobs outside of Mujeres. Any money earned through sales goes into savings for the co-op space. The group keeps track of the hours and work each person puts in. If they need money for something, they can borrow from the fund, but they're expected to pay it back.

Why mujeres only?

"Because of jealous husbands," Díaz jokes. But that's not the only reason.

"The first idea is because we want to fix the situation, the economy, in our houses. Every house, too many men say, 'You're not working, you stay at home.'" Díaz said. She said when only the men in a household work and control the money, sometimes it's spent on alcohol and parties, leaving little left for food. When that happens, Díaz said, families have to turn to the government for support.

"And that's not cool," Díaz said. Through Mujeres, they want to show women that they can help support the house and the whole family -- that, "You can do it, not only him."

"We're powers. We can do many things, not only get a husband, babies, home," Díaz said. "We try to change the mentality. Because some ladies, they don't want to speak in the front. They don't want to say anything -- if it's in Spanish, in English, whatever."

Díaz said she's seen women who've joined the co-op gain confidence, take on work opportunities and become more outspoken.

"I can say the situation for many women in the group is changing," she said.

The Mujeres built up the co-op on their own.

"Everybody's scared," Díaz said. "We don't have any budget. We don't borrow money from nobody."

It was important to them to do it without loans or outside help.

"We know different places that we can get more money faster, but I feel that it's more powerful if we work together," García said. "If we saved up that money to set up our own place, that will be more worth it. And at the same time, we learn more."

They learned independently how to gain financial independence. They took business, accounting, English and computer courses online, or at Re:Vision. They read books and watched a lot of videos, learning little by little what it means to run a business -- how to hire an accountant, handle taxes, get a business license, manage the books -- and all of the expenses, laws and regulations that go into it.

García says they share a lot of what they learn with other people in the neighborhood, which she says doesn't have much access to economic education.

"I feel that the things that you learn, if you don't transfer to other people, it's not worth it," García said. "I feel when you are open to transferring those kinds of things, it's more powerful."

She said a lot of the families she knows don't have savings because they spend money as soon as they earn it. She said many of them came from countries where they had very little, and are excited about the opportunities to buy things they never had. Because of that, they might not have money on hand when an emergency comes up.

"I feel that we spend a lot of money on things that we don't really need," she said. "It's a way to feel that we are better, and that we have a better life now. But at the same time we lose opportunity to really have a better life."

She said part of it is a stigma around saving money.

"Saving, that was like, 'You're a bad person,'" she said. "Because how can you be saving money when you have your brother that needs money?"

García said when she saved her first $500, she initially felt like she was a worse person.

"And then I said, Why do I have to give them my money, when I worked all day, when they spend the money smoking, when I did all the work?" she said. "I had to change my mind to understand why it's not bad for me to have the money, because I worked for the money."

She says she doesn't tell family and community members they should start saving. She doesn't need to. Instead, when they see that it's working for her, they ask how she does it, and she shares resources and insight with them she's picked up through Mujeres Emprendedoras. García said she even inspired her sister back home in Mexico to open a savings account, that she's been reading the books García sent her, is saving up to buy a car.

"For me to see that change," she said. "That's something that is great to see."

The impact they've made in the community is hard to measure. It's through anecdotes like these that Mujeres feel that they're helping to combat displacement. Since García started developing these skills and having conversations with community members, she said she's helped discourage several families from moving out of their homes. Many residents, she says, sell their homes thinking they'll be able to buy a bigger one, only to find they they don't qualify for the loans necessary to buy a house in the current market. She said she's encouraged families to look into buying a new home before they put their house on the market, so they know what they're getting into. Those people decide not to sell, and are able to keep their homes.

As for the co-op, García says they're inching closer towards having their own space. It may be several months before they'll have enough saved to cover a 12-month lease and utilities, plus money for supplies and equipment. Once that's set, García estimates it'll still be years before they make enough to buy each of the Mujeres a house.

"But I feel that we will do it," she said. "I am sure of that."