If developer Revesco Properties completes its River Mile project in 25 years, 15,000-residents will be living in high rises near the banks of the South Platte River, a part of town with a toxic history and a moderate risk of flooding.

The development will run from Confluence Park to Dry Gulch. The exact footprint of the project is still being negotiated.

To the chagrin of Denver kids, the River Mile will take over the land where Elitch Gardens sits. The first part to be developed will be the amusement park's parking lots, which fall outside the floodplain, making phase one an easy win for Revesco.

On the Urban Land Institute's October bike tour of new developments along the South Platte, Greenway Foundation CEO and River Mile champion Jeff Shoemaker dished about where Elitch might be headed: "I'll just give you one guy's projection. I think it's going to be a delightful competition between Arapahoe and Adams counties. There's a Sporting Goods stadium and this thing called Gaylord, and so who knows? But it's in play, and we don't know yet. Well...I know just enough to always be dangerous. It's in discussions."

Kayakers may be as frustrated as kids by the River Mile's impact. Revesco will demolish the popular whitewater chutes at Confluence Park to change the grade of the river and replace them with much humbler water features more likely to be used by river surfers upstream.

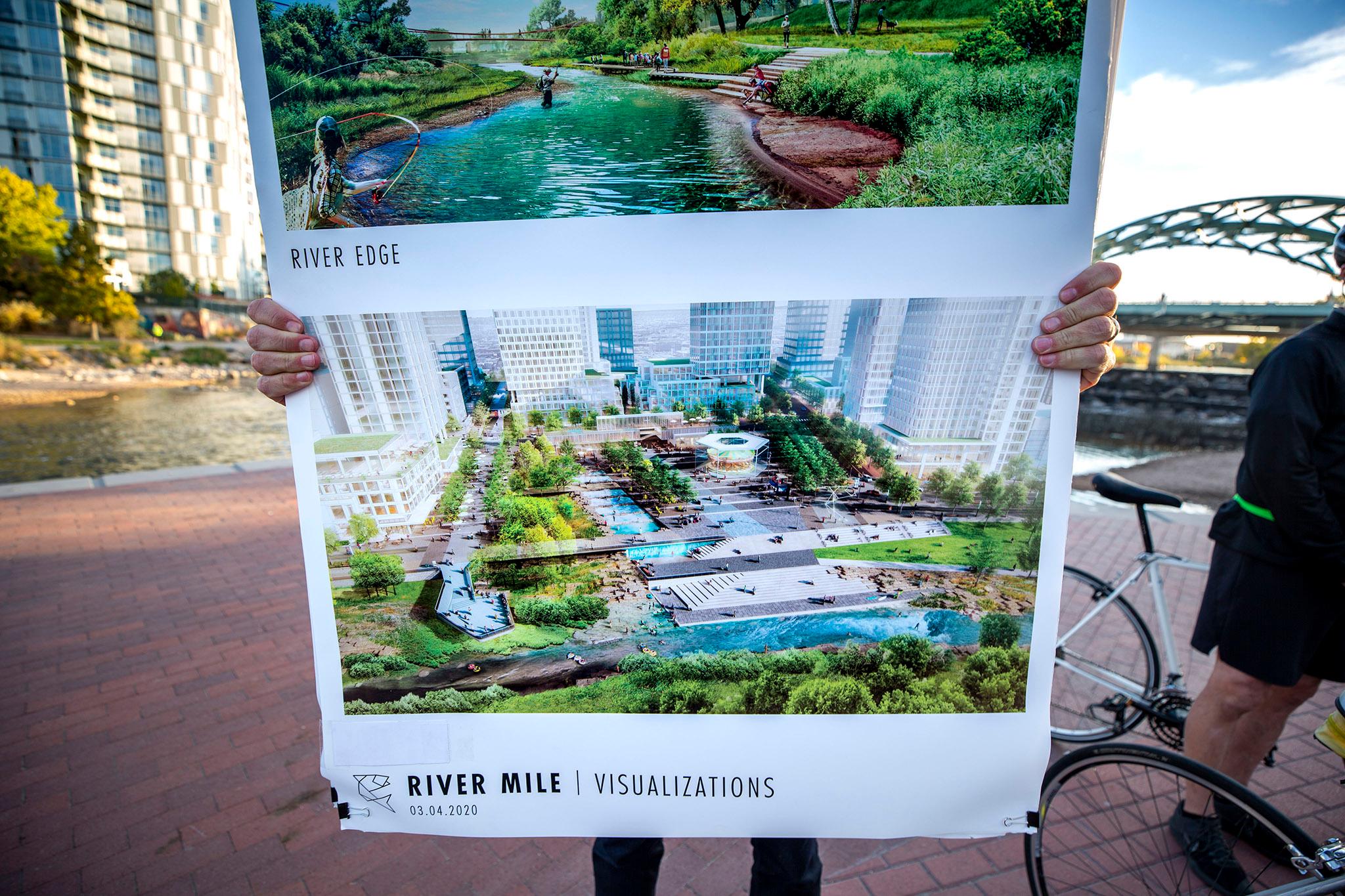

Yet Revesco is betting that losing the enthusiasm of kids and kayakers in the short term is a small price to pay so that the ever rising number of Denver residents will have yet another place to drink, dine, work and live. Retail, high rises and riverside restaurants, bars and shops, along with massive art installations, entertainment venues, restored landscaping and even trout fishing will come to the area.

"The concept is to be dense so that people can live where they work and play where they live and do all that and not really need cars," said Greg Dorolek, co-president of Wenk Associates, the landscape architecture firm behind the project. The hope is that through density, the developers will minimize traffic impact with really narrow, walkable streets, bike access and new pedestrian bridges.

Much of this will be built on a floodplain where people have tried to create a life and build an industrial economy only to have it swept away by rushing waters.

How could building so densely where it floods be safe?

On the bike tour, we asked Mile High Flood District Manager of Government Relations David Bennetts whether it made sense to build a massive development on what he described as a hundred-year floodplain.

"It is what it is," he said.

We pressed him for more comforting details, and he pointed to a retaining wall next to Cherry Creek, near Confluence Park, where water nearly spilled over onto Speer Boulevard when it flooded in 2013.

In short: floods happen.

Even though things are safe most days in Denver, where rain is a rarity, rivers aren't entirely predictable. Storms come. And from what those 2013 floods suggest, major flooding could happen again.

So, really, is building near the South Platte River a good idea?

"It is what it is," he repeated.

Since colonization, the history of the South Platte River has been fishy for prospectors looking to strike it rich and build a good life -- even when fish couldn't survive in the industry-and-sewage poisoned water.

Before settlers came, the land around the South Platte served as a home for the Arapahoe and Cheyenne. As Europeans secured the land by pushing the Indigenous people out through a mix of treaties and massacres, newcomers began to use the river as a resource to exploit. It would become the lifeline of a burgeoning city.

"They needed water. They needed trees. They needed all of these things," said Bennetts. "So they created ditch diversions to divert the water for their needs. And they used it to power plants...to generate power, to cool the power plants. And really, they took everything they needed from the river, and then when they were done with it, they dumped everything they didn't want back into it."

Those destructive practices lasted for more than a century.

"You had raw sewage going back in the river, trash, cars," he added. At the National Western Center, when workers would slaughter animals, they would dump what wouldn't be consumed into the river. "So it was really terrible the way we treated the river at the time."

Over the years, Jewish, Italian and other immigrant and working class communities bought cheap land in the floodplains and experienced firsthand just how harmful the South Platte could be to those who dared live near its banks. As those communities built wealth, they moved to higher ground.

When the South Platte River flooded in 1965, everything changed.

In '65 a storm rolled into Colorado, and 40,300 cubic feet of water per second rushed down the South Platte River, killing 21 people and trashing $543 million in property -- more than $4.7 billion in today's currency. That's a lot of water. In normal times, the river boasted a flow of around 300 cubic feet per second, according to Jeff's dad, former Colorado lawmaker Joe Shoemaker's 1981 book Returning the Platte to the People. The Denver area was hit hardest, and the river's toxic history surfaced and spread wherever water flowed.

The flood revealed to politicians like Joe just how badly Denver trashed the very river that allowed the city to form in the first place.

In 1969, he helped launch the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District -- which was rebranded the Mile High Flood District for its fiftieth anniversary. A year after forming, the District launched the nation's first floodplain rules and has established itself as a leader in managing regional flooding.

Bennetts was one of the District's first employees tasked with doing maintenance on the river. He remembers just how nasty the water was.

"I looked across the river, and there's like six or eight caskets kind of open, and I couldn't figure out what the hell was going on with all these caskets on the river," he said. It turned out that a factory was dumping its poorly manufactured caskets into the South Platte. "They just kicked them out the back door, into the river, and allowed the flow to take them downstream."

Jeff remembers just how bleak the river and its surroundings were before the flood.

"What's important for you all to know is there were no parks," Jeff said. "There were seven landfill dump sites. There were no trees, no trails. There was nothing."

After establishing the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District, Joe Shoemaker spent the rest of his life championing a vibrant future for the South Platte River. His family carries on that tradition.

In 1974, Joe founded the nonprofit Greenway Foundation to turn the blighted river into a regional treasure by building all those things that were missing in 1965. The group planted trees, built parks, bike trails, and whitewater chutes for kayakers, cleaned up trash and restored the waterway as a place where animals could survive and children could come and learn about just how vital the South Platte is for Denver.

The Greenway Foundation has also been boosting a commercial future for the South Platte as a place where urbanism can thrive. To fulfill its vision, the group works with the private, public, philanthropic and political sectors.

Revesco's River Mile development is the culmination of the Shoemakers multigenerational work: cleaning the river and restoring its value to the community by turning it into a destination.

"This project," said Jeff, "is the epitome of my family's dream."

To keep that dream from becoming a natural-disaster nightmare, the South Platte River will need to be rechanneled and redesigned.

Were the River Mile to be built without reengineering the South Platte to prevent future flooding, there is no doubt the project would be too risky to build in good conscience.

The river, while a natural force, is hardly in its original state. Chatfield, Cherry Creek and Bear Creek reservoirs protect Denver from the South Platte flooding, as do past rechanneling projects that need a refresh.

Brooke Seymour, the Mile High Flood District's engineering services manager, cheerily shared her sobering thoughts on flooding: "There is no such thing as no risk. Everywhere has flood risk."

But risk is higher in some places than others, and next to the South Platte River is one of those riskier spots. The evidence: Water already drains into Elitch Gardens.

The risk-assessment data Revesco will use to rework the river comes from the Mile High Flood District. By federal mandate, designs have to take into account the 100-year flood, a devastating event with a 1% chance of occurring.

The Mile High Flood District data will help the Colorado Water Conservation Board take risk mitigation even further, incorporating the possibility of a 200-year flood, which would be an even more devastating yet unlikely event. The local data even takes into account future land-use hydrology, looking at greater flood risk caused by more roofs, more pavement, more pipes and other infrastructure causing water flow to occur at the surface -- what flood experts call "urban drool."

"Once we knew that there was a development happening, we shared that information so that they can make informed decisions to make sure we are building responsible development based on the best available information," Seymour said.

There are no government funds -- local, state or federal -- to re-engineer the South Platte River to take the risk of flooding away.

With no government funding for reengineering the South Platte on the table in the foreseeable future, Revesco itself will foot the bill for the redesign.

"It's very difficult to imagine, but this river will be about half of 1/3 of its width today," said Dorolek. "The river's going to be much narrower, much deeper, higher restoration potential of those banks, better habitat. And we'll be able to fill Confluence Park up with trees and shade and really bring the city to this part of the river."

The reengineering alone will cost millions, though its final budget will be based not just on the predicted work but the unearthed toxic surprises likely to be found along the way. Revesco hopes to finish the South Platte River redesign over the next two years.

"That's benefiting a lot more than just their development," said Seymour.

No doubt, the project will be one of the most ambitious developments in Denver history and comes with risk. But Revesco and the City of Denver are confident, as of now, that they can succesfully rechannel the South Platte to safely pull off the project.

As Seymour explains, Revesco's reworking of the river is one of the major reasons the City of Denver and the District back the plan. The engineering will benefit not just the developer and the people who will live, work and play along the River Mile but also the broader community itself, which lives with a moderate risk of being flooded now, as 2013 proved.

"The developer is actually paying for and implementing those regional improvements, which is a benefit to the greater community," Seymour said. "But then obviously, the driver for him or her is that they get to develop."

The development in the works involves a tolerable level of risk based on the probability of future flooding, she explained.

"There are many layers and levels of floodplain development standards to protect the community and improve public safety," Seymour added. "And it's a matter of trying to balance public safety and responsible development with your rights to be able to develop and use your property."