The Far Northeast Warriors varsity football team knelt in front of head coach Tony Lindsay Sr. as a celebrating crowd filtered out of Evie Dennis Stadium on Oct. 29. East High nearly took away the Warriors' shot at winning the league title, but their deciding field goal came up short and bounced off the uprights. The stadium was silent as the ball sailed through the air. When the ball hit the metal, the Warriors and their supporters went berserk.

"You know, to become a great football team you've got to go through this," Lindsay told the Warriors after the teams shook hands and the Angels disappeared from the turf. "To be a good team you have to go through all of it. And then next year comes back huge, and it is going to come back huge. Believe me, it is."

It wasn't just a win. It wasn't just senior night and the last regular-season game for the six players who would graduate and move onto the next stages of their lives. This was the end of a long and difficult era, years of fighting for equity and representation both on the football field and across the Montbello and Green Valley Ranch neighborhoods.

In 2010, Denver Public Schools voted to phase out Montbello High School, the centerpiece of the city's far northeast community. Its closure was a huge blow to longtime residents. But the school's football team remained. The Warriors haven't had a dedicated student body since, and have pulled students from nearly a dozen schools to fill their rosters.

The comeback Lindsay spoke of in his huddle was about next year. In 2022, a school will reopen in the old halls of Montbello High with students who will call themselves Warriors, just like Lindsay's players.

A unifying home team might help the team reclaim its status as a force in Colorado sports. But beyond the field, Montbello High's return could restore a crucial neighborhood symbol and start a new chapter for many residents who have long felt unheard by those in power.

Lindsay's team was central to the movement to resurrect Montbello High. The team's coaches became activists that drove the movement to demand that DPS reinstate a comprehensive school in the area. As they fought for their players, making sure the team had access to gear and facilities, the coaches found themselves in a bigger conversation that rippled far beyond athletics.

Tony Lindsay Sr. waited the better part of a decade to lead the team as head coach.

He was a coach at Montbello High in 2006 when he applied for the top spot. His boss told him he'd be better off leaving the school altogether.

"He said, 'If I was you, the first chance you got to leave, you should go,'" Lindsay recalled. "'They're going to come in here and they're going to close this.'"

It hurt Lindsay to leave, but he wound up leaving for a coaching job at South High School. He hired his sons and, together, they led the program to victories.

His old boss was right. In 2010, DPS voted to disband Montbello High School and replace it with an array of small specialty schools across northeast Denver, which is home to some of the city's densest populations of Black and brown residents. Three schools would take up residence in Montbello High's building.

Administrators argued closing the school was necessary to improve graduation rates, but their decision drew crowds of protesting parents and teachers to public meetings. Montbello High was about more than education, they'd argue. It was the heart of the community. The shutdown was such a big deal that some residents called it a "Hurricane Katrina" moment that could destroy the area's very social fabric.

Administrators knew the new configuration would come at a cost, so they created a regional athletic program that they hoped would bridge the new gap between families across the neighborhoods. The Warriors' athletic department became a co-op of a half-dozen smaller schools, whose students would play for the regional program. Kids who attended other schools without teams in the area could play for any school in the district, but many would choose to join the Warriors.

While DPS funded the program, the scattered setup made it harder to rally additional money from alumni that schools with huge centralized networks, like East and South, could muster. Attracting fans to fill bleachers during home games became more complicated. So did getting students to show up to practice on time; it's not easy to wrangle a group of kids who all get out of classes at different hours.

Time on the field did give students a chance to connect with friends with whom they may have otherwise lost touch. But the team ultimately failed to recreate the community hub that died with Montbello High, former DPS superintended Tom Boasberg told us, though through no fault of its own. The smaller schools that replaced Montbello High flourished and established their own teams for sports like soccer and volleyball, which Warriors coaches said took the wind out of the regional program. As the years passed and Warriors athletic directors came and went, the old Montbello High football facilities fell into disrepair.

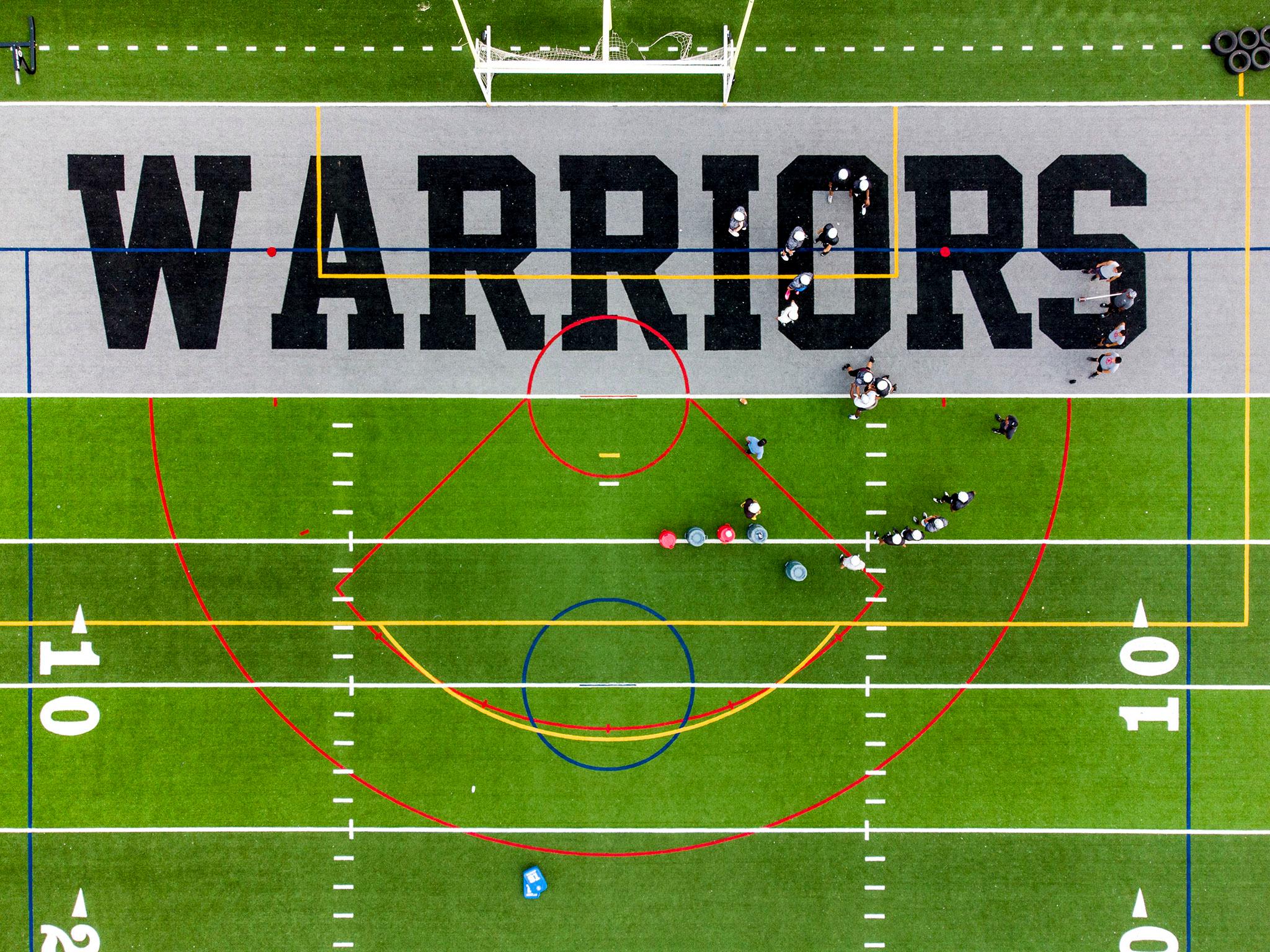

Lindsay still dreamt of returning to the Warriors, and in 2017 he got his chance. But things had changed. The practice field's turf, once home to a powerhouse organization, had faded beyond recognition. Weeds grew on its borders. The field's lights were broken, so staff had taken to illuminating night practices with construction equipment. Locker-room showers had been sealed shut and converted into storage. Not like there was hot water, anyway. Lindsay was appalled, and frustrated DPS would let things slide.

"You gotta be kidding me," he recalled thinking to himself. "Just be fair and give them what everyone else has. Don't be cheap with us. Don't be cheap with the kids."

For some in the far northeast, Montbello High and its football field were part of a larger story about an underinvested neighborhood.

In the spring of 2021, Evan Partida was a graduating senior at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Early College when he helped secure the Warrior's first-ever state football championship. The Montbello and Green Valley Ranch neighborhoods exploded in celebration, throwing a parade to honor the players. Alumni showed up wearing their old black and silver jerseys and T-shirts. It was an occasion to revel in neighborhood pride, and a moment he'll never forget.

"It was just - there's no words for it," he said. "All that truly showed family. And that's what we are over here, family. And there's no taking us out of it."

Before he started classes at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, Partida showed up to nearly every workout last summer to lead his former teammates in the weight room. He said the guidance he got from his coaches set him up to graduate and head to college, and he felt a responsibility to return as a mentor when he had the time.

"Even though they're tired of seeing me already, you know, I love them. I'll protect them in a heartbeat. They need a shirt, I'll give them the shirt off my back," he said.

Partida was young when DPS phased out Montbello High School, but he's well acquainted with its story. It's hard to avoid if you grew up in the area.

To him and a lot of people in the area, the closure fits into a bigger picture. On the one hand, this corner of the city was an ideal place to be a kid, tightknit and full of community support. But Partida said the area grapples with an undeserved bad reputation, and that it hasn't always been given a fair shake. For example, he said, Montbello sits just across from the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, where the U.S. military developed chemical weapons after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

"I mean, if you look at it, Montbello is right there next to what used to be a bomb testing site. And you know, they kind of pushed minorities out into those neighborhoods," he said. "But you know, we don't really see each other as minorities. We don't see brown, Black. We don't see any of that. No, we see a brother, we see a sister, we see family over here. Are we pushed into a little corner? Most definitely. But at the end of the day, pushing us in that little corner just brought us closer together."

The reputation issue is a theme that runs through the area's history. After Developer Perl-Mack broke ground on Montbello in the 1960s as a planned community, Black veterans and their families bought homes with GI Bill money and established it as one of the city's most diverse areas. Residents and reporters at the time described Montbello as a "city within a city," its own universe at Denver's edge that was at once separate and a part of the broader population. Longtime residents describe Montbello's early days as an era of endless potential.

But things had changed by the 1970s. Community groups began to accuse realtors of steering white buyers away from the neighborhood, complaints that got the attention of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission. Parents demanded that a neighborhood high school be built. Perl-Mack included a school in its plans for the area but later refused to give the city land to make it happen. Taxpayers gave the developers $136,000 to secure the site that would become Montbello High. Soon after the school opened, in 1981, a recession decimated property values in the area and led to foreclosures.

"The subdivision was branded 'Montghetto' by residents from other areas," a Rocky Mountain News reporter wrote in 1992. "Today, Montbello residents are fighting that image."

Headlines about the neighborhood's "self-image problem" showed up in newspapers for decades. But many people who grew up in the area talk about deep pride in Montbello and Green Valley Ranch, which was developed in the '80s. For them, the problem was never about self-image. It was about stigma that flowed in from whiter, wealthier parts of town and journalists who seemed to only show up when there was bad news to write about.

On some level, these perceptions don't mean much to people who have long advocated for this community's success.

"I don't care what outsiders think, feel or say about what we do. We know what we do. God put us in this fight for a reason. So we don't need anybody's approval," Gabe Lindsay, Tony's son and assistant coach, said one day during practice.

But his colleague, coach Brandon Pryor, said people in power can make misguided decisions if their perspectives of the community aren't deeply rooted there. Though Boasberg said he still thinks closing Montbello High was the right thing to do in terms of improving graduation rates, and though the move was backed by elected officials like Michael Hancock, who represented the far northeast on Denver City Council at the time, Pryor and Lindsay both said the decision represented a fundamental disconnect between those in power and the residents whose lives revolved around the school.

"That's what happens when you come into a community paternalistically, like you have all the answers," Pryor said. "They snatched the heart out of a community when they did that. And a sense of pride died with that. It was like a helpless feeling. And you could feel that it was like a rippling effect across the community. And now we're trying to restore that."

These football coaches never meant to become activists.

After Lindsay returned to Montbello, he, Gabe and Pryor began taking meetings with administrators to bring the facilities back to working order. Gabe and Pryor felt that the decrepit field was a symbol of larger issues facing the neighborhood. They soon moved their attention to other problems.

Both said they never expected to become so invested in education or policy, but they felt they had to act when their roles as coaches brought them so close to neighborhood issues.

"We just started noticing stuff little by little," Pryor recalled during one afternoon practice. "When I started to see how our kids are being harmed and hurt and what they're being subjected to, like, it's just in me to fight."

Their journey to advocacy began when they started attending DPS board meetings, sounding the alarm over the need for a library when the one in the high school closed. Eventually, Pryor and Gabe were asking for Montbello High itself to return. The message resonated with longtime residents who joined the effort.

Their advocacy paid off. In 2018, DPS restored the library in the old Montbello High building. And in February of 2021, the school board voted unanimously to reopen a full-service high school in Montbello High's building (the possibility of closing the three smaller schools that lived in the space drew its own share of controversy).

While former Montbello High students and teachers have been deeply involved in the movement to bring a comprehensive high school back to the area, many residents trace the effort back to the Warriors football program.

Gabe, Brandon and Brandon's wife, Samantha, also helped found a new school, the Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy. The HBCU-style high school opened this year with the goal of sending high-achieving students to Florida A&M University on scholarships. While they hope Montbello High's replacement will become a neighborhood hub and create a newfound sense of pride for kids in the area, Gabe said this additional, community-driven school is also necessary right now.

The fight over Montbello High has always been bigger than a school. The Montbello Warriors have always been bigger than sports.

Leonardo Ramos, a senior this year at STRIVE Prep - RISE, was a skinny kid when he showed up to Warriors football practice as a freshman. But by the time he reached his senior year, he'd bulked up and found his place on the team.

Nicknamed "Crazy Leo" for his relentless attacks on quarterbacks and linemen, Ramos' energy and charisma made him a de facto leader among his peers. At the start and end of each practice, he'd lead the team in a chanting frenzy as players rushed into a huddle.

"One, two, three - Warriors! Four, five, six - Family!"

But Ramos' season didn't go the way he'd hoped. He was recently diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis, a kidney disease that shuts his body down with cramps if he pushes himself too hard. During the Warriors' first varsity game of the season, Ramos began to feel tingling in his hands and feet as the clock counted down to halftime.

As his teammates rushed out of the locker room to begin the third quarter against the ThunderRidge Grizzlies, EMTs prepared to load Ramos into an ambulance. The medics stuck an IV in his arm and staved off a full-on cramp attack, but he spent the night in the hospital and had to sit out the next seven games.

For years, Ramos' life revolved around football. His whole plan after graduation involved some kind of college ball, and that suddenly became a less likely scenario.

But Ramos said his coaches have prepared him to become more than an athlete. Those lessons will guide him wherever he ends up.

"Football shaped me, who I am. It taught me leadership. It taught me confidence. It taught me to be courageous. It taught me how to be a man," he said one afternoon on the sidelines of the field Lindsay and his colleagues fought to restore. He still couldn't dress out in pads and his jersey. "Everything happens for a reason. It's a book written. If this happens, it's meant to happen. Wherever it takes me, it takes me."

Setting kids up on a path is the kind of thing that gets Warriors coaches out of bed in the morning. For Tony Lindsay Sr., that's more than a turn of phrase. Though he's the team's leader, his coaching job doesn't pay a living wage. Lindsay heads to work at about 4 a.m. every day to drive an RTD bus between Green Valley Ranch and Parker, then heads to his field to train his players each afternoon. It's a grueling schedule for anyone, let alone someone in their 60s.

Lindsay and his staff are driven by a sense of responsibility -- that their work on the field will help secure the futures of the students they fight for.

"We have to protect our kids, and we have to do it our way. We protect our kids the best way we can through this football. So we use that to bring them in. And as they come in, we grow them up and we talk to them and hopefully they learn," Lindsay said one evening in a near-whisper; talking about this stuff usually brings him close to tears. "We all have our purpose, and this is our purpose."