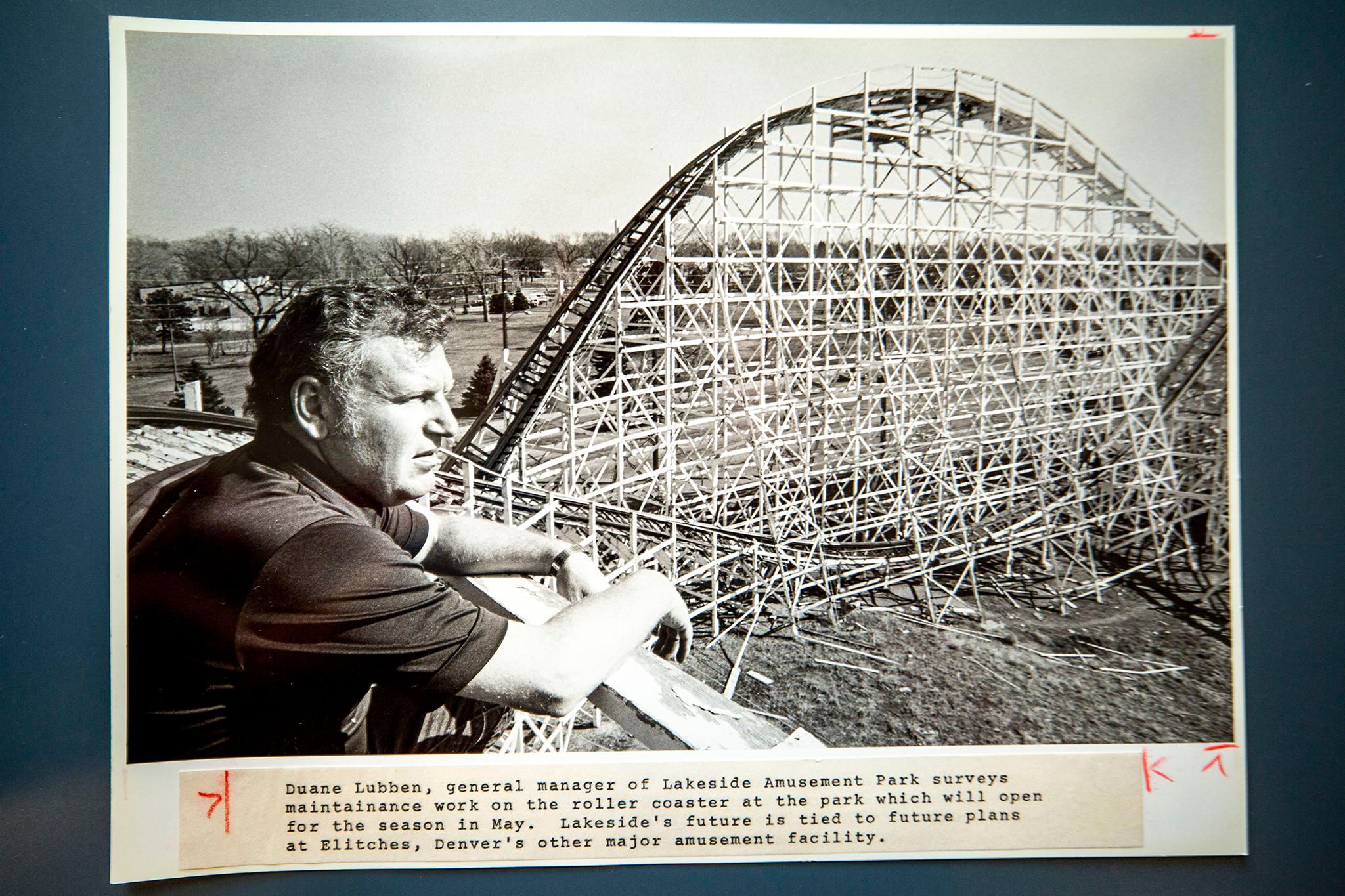

We're making our way through a massive collection of Rocky Mountain News photos that are now in the Denver Public Library's archives. We polled our readers about which letter "A" subject file we should explore, and you voted for "Amusement Parks - Lakeside." (If you want to get in on the next round of voting, sign up for our newsletter!)

A thesis and a brief history:

In 2012, University of Colorado PhD candidate David Forsyth wrote a thesis on Lakeside, which is what we're using for the bulk of our historic context. He later published a book on the park with all he'd learned in his research.

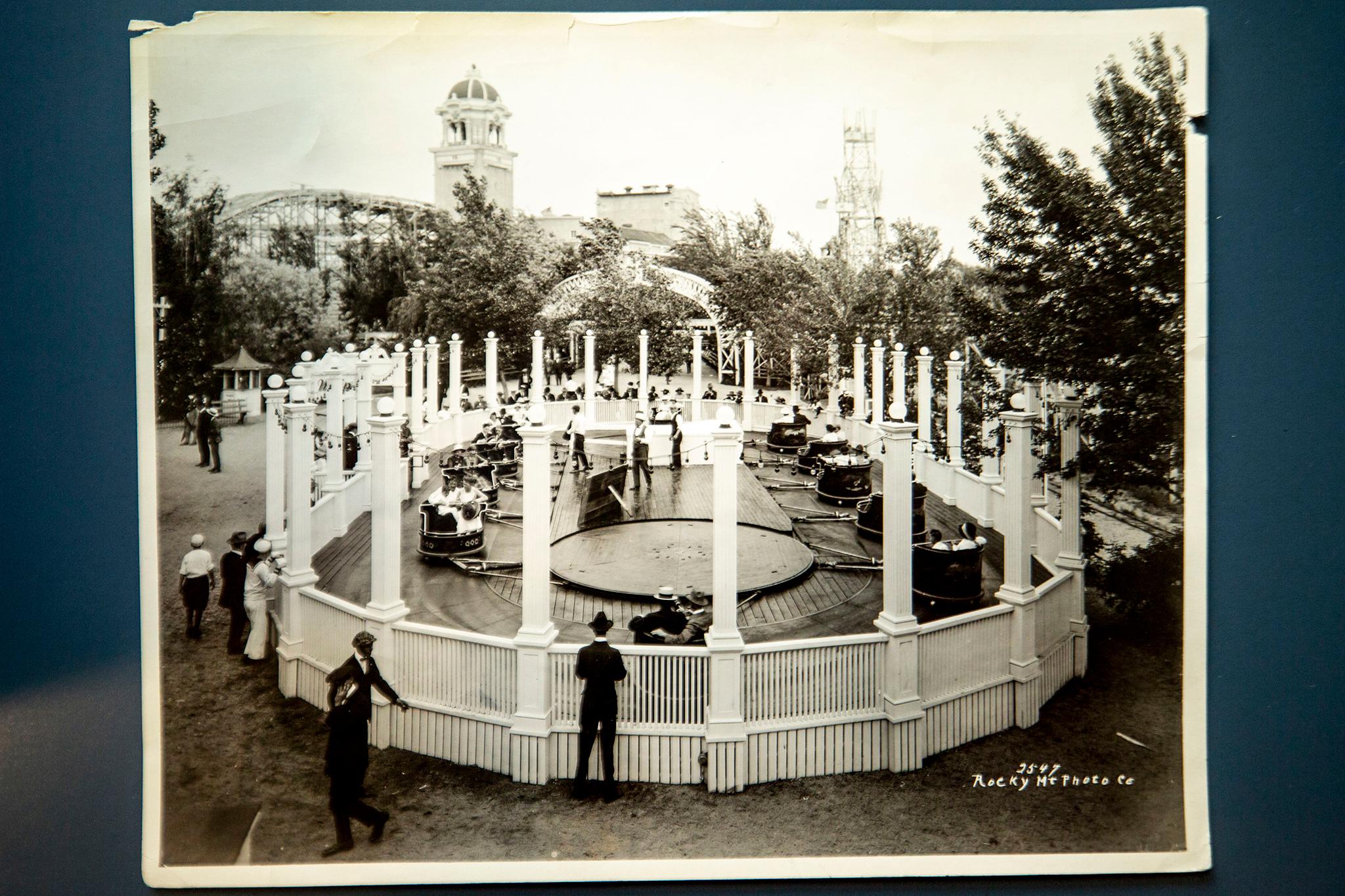

Plans for the park were revealed in 1907. The project was helmed by Denver brewer Adolph Zang (who also built the mansion named after him in Capitol Hill).

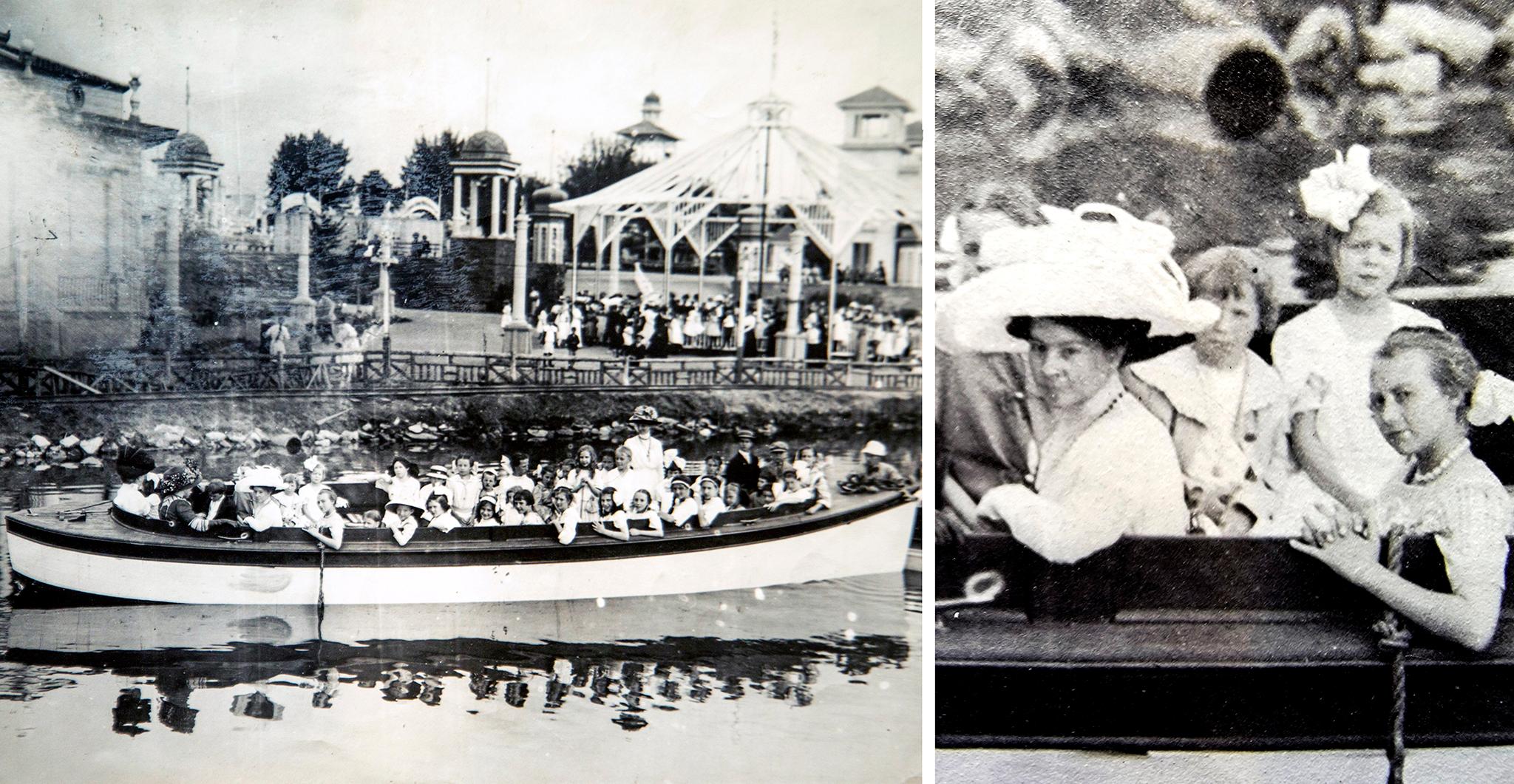

Lakeside's white columns and ornate tower were part of the larger "City Beautiful Movement," which became very popular after Chicago's 1893 World's Fair. City leaders across the nation began investing in architectural projects and efforts to open new public spaces that drew from classic Greek and Roman designs. As Zang sought to create that vibe in Lakeside (which is in its own, separate town), Denver Mayor Robert Speer worked on his own City Beautiful vision for what would become Civic Center Park.

Forsyth told us City Beautiful projects were generally exclusionary.

The stewards of New York City's Central Park, for instance, used signs to keep people off grass and out of fountains that became ways to control who could use the space. Civic Center Park was an exception, he said, since Mayor Speer's vision of City Beautiful was more inclusive. Zang's park, however, was created in line with other projects of the day.

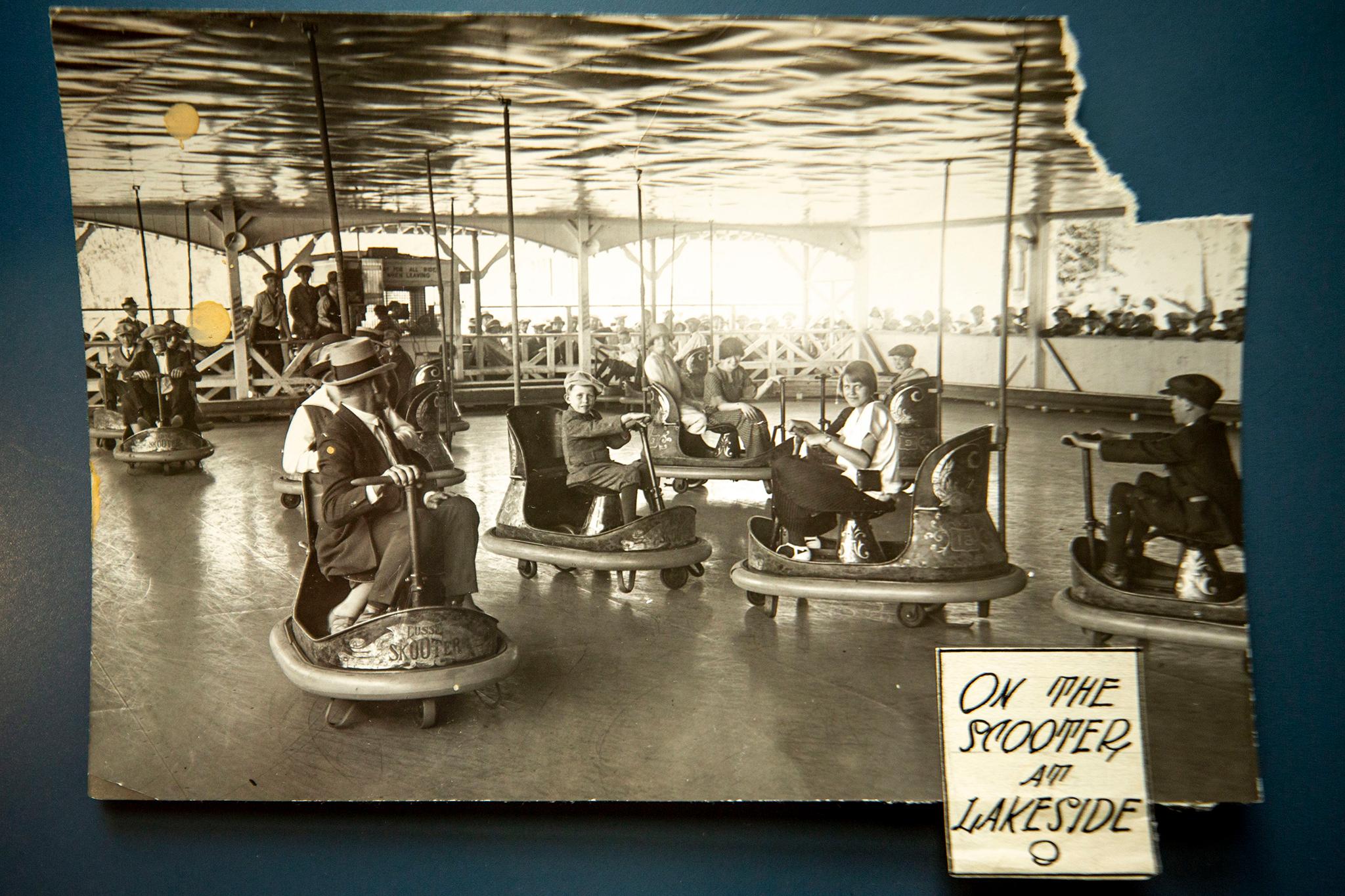

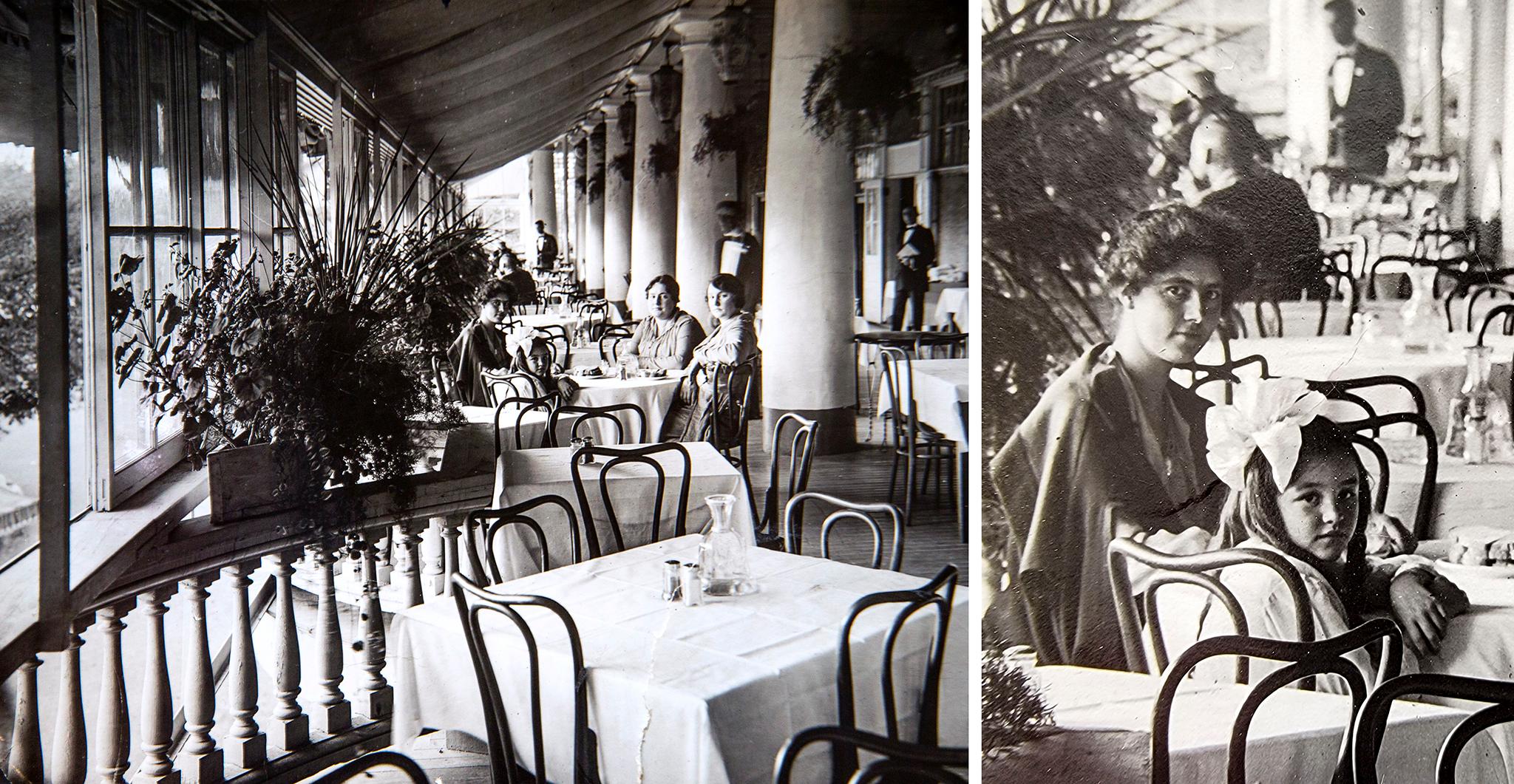

"Lakeside, when it started, was really the elite, upper-class amusement park," Forsyth said.

That faded over time, to a degree.

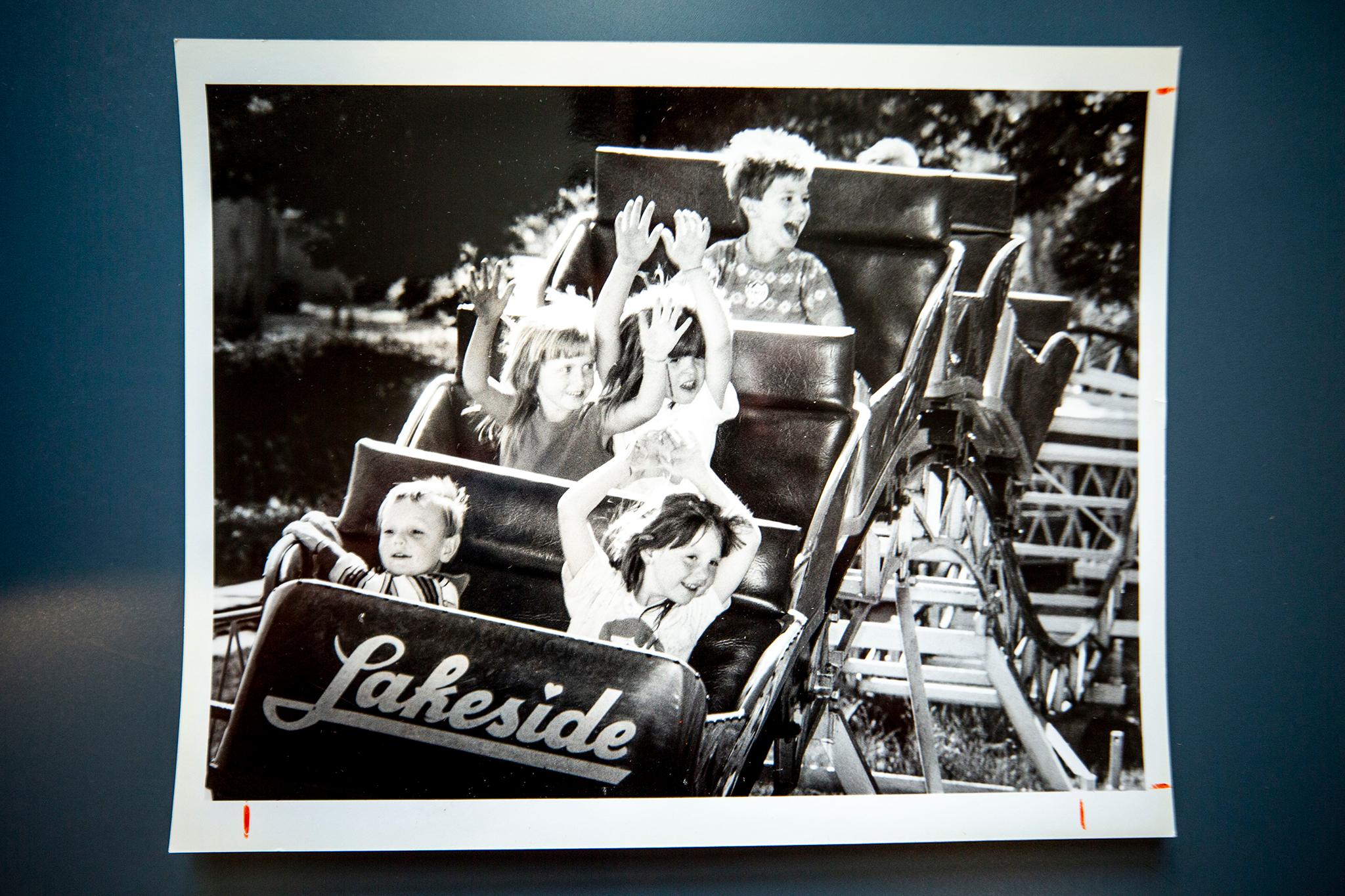

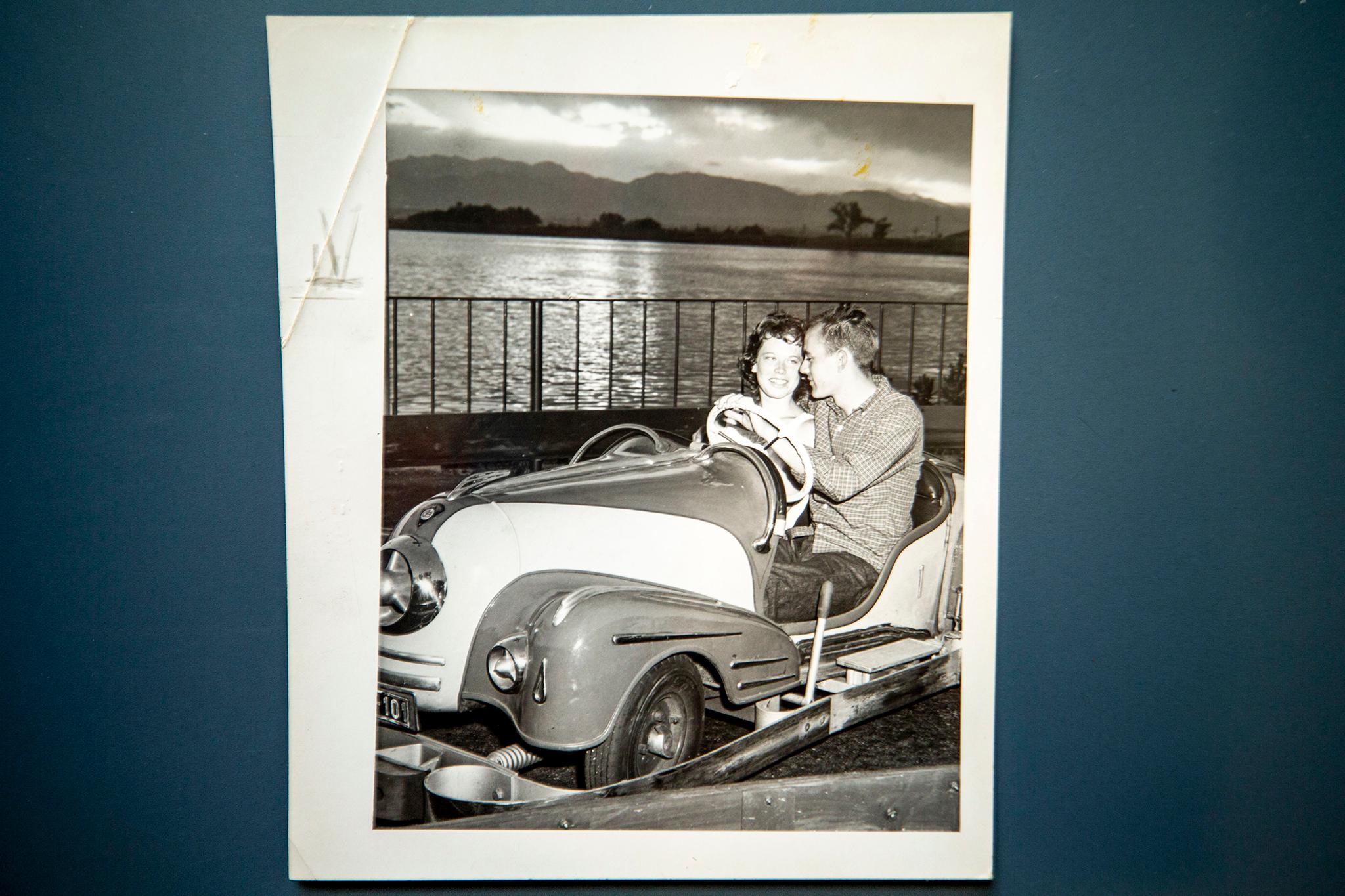

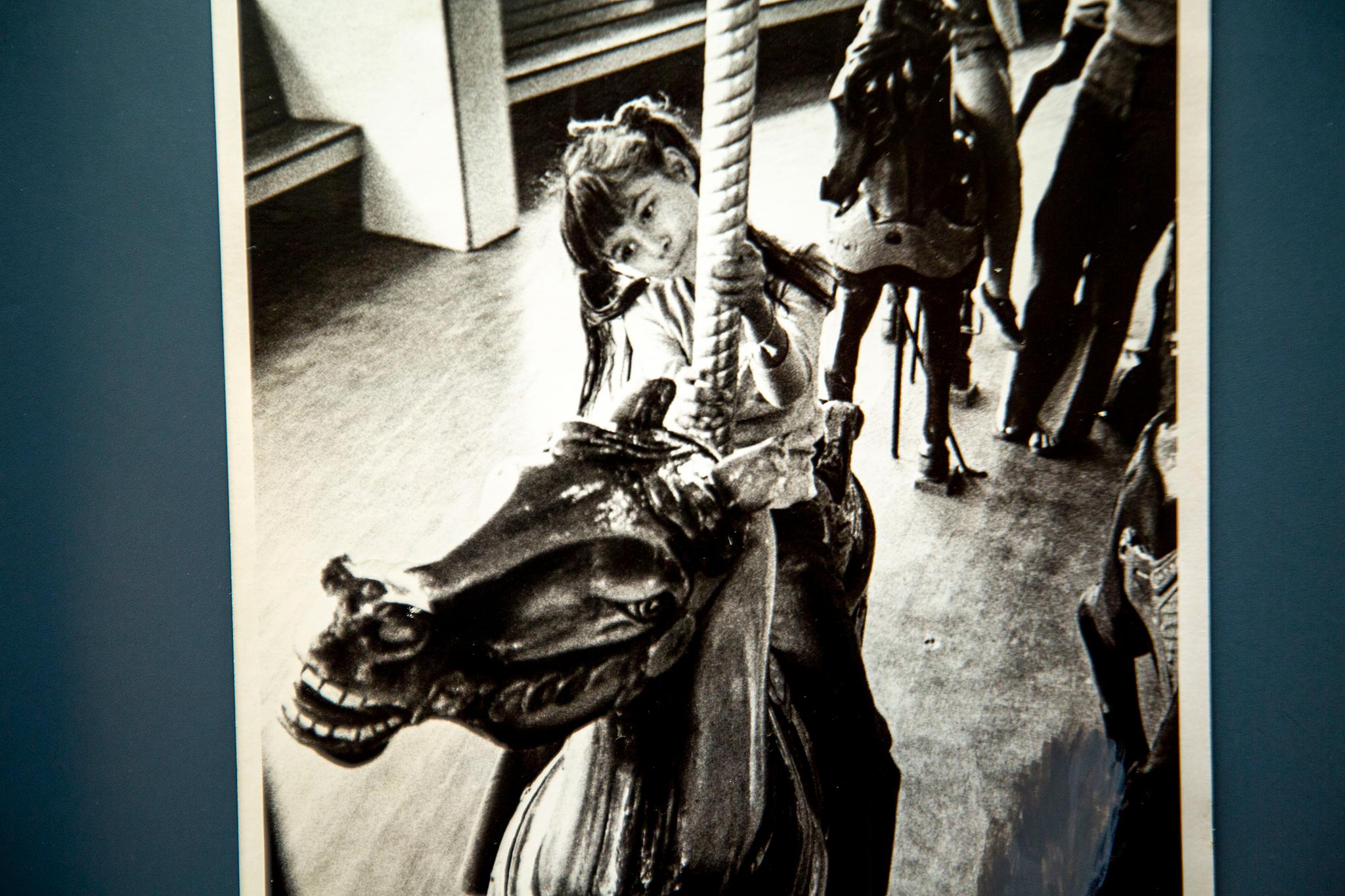

"When that image began to fail the park, new owners demonstrated their incredible ability to reimagine and reinvent the park, creating a typical working class amusement park that still managed to be a bit different," he wrote in his thesis. "Once customers were inside the decent and respectable park, social roles were leveled out and up for grabs as people from all classes shared the same experiences."

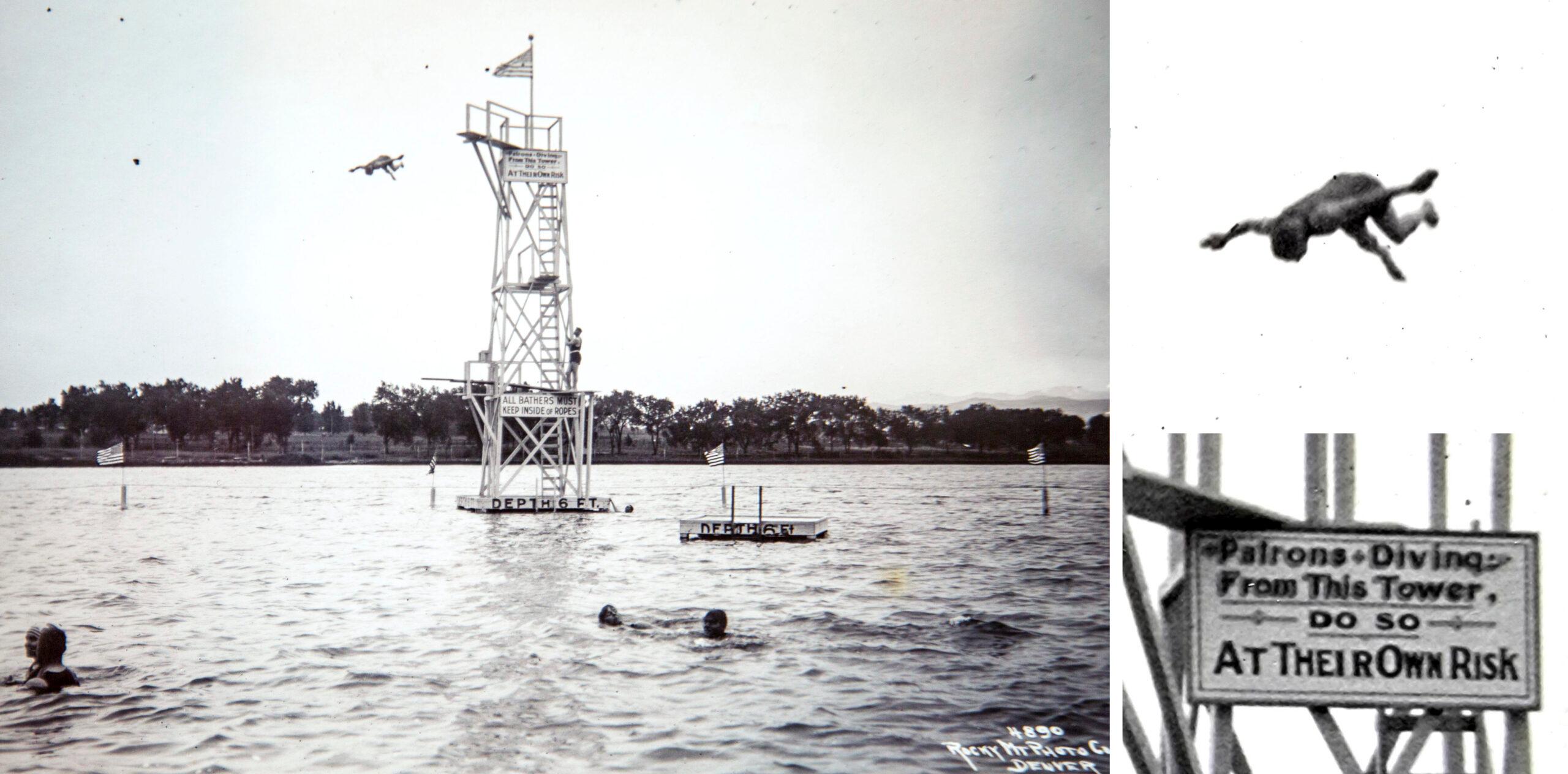

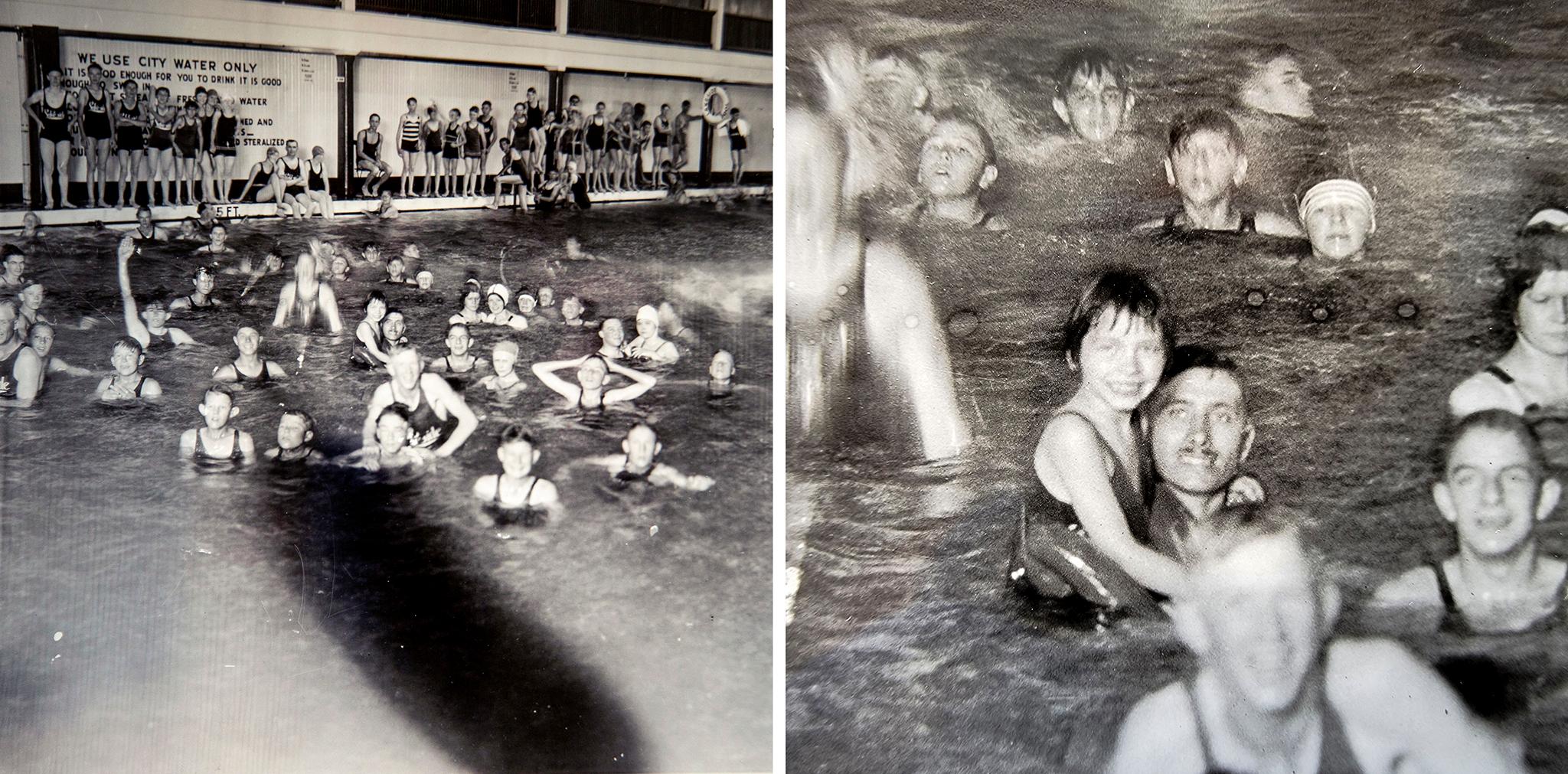

But the extent of that multi-class melting pot was limited in Lakeside's early days. While classes began to mix on thrill rides and in its swimming spots, Black customers remained barred from entering. Forsyth said Lakeside was closed to African-Americans from the day it opened, though that discrimination never officially extended to local Hispanic and immigrant residents. Black musicians were allowed to perform at the park but were forced to spend their off time somewhere else. This was also true of downtown, where Black artists were invited to perform in clubs but weren't allowed to lodge in the heart of town.

Race-based policies were very common in early 19th-century amusement parks, Forsyth told us, and were adopted by other classic Denver spots like Elitch Gardens. Manhattan Beach, a fun park at Sloan's Lake, and Arlington Park, located at current-day Alamo Placita Park, were also likely segregated; though Forsyth doesn't have hard proof of this, he has seen evidence that each typically opened exclusively to Black residents one day each season.

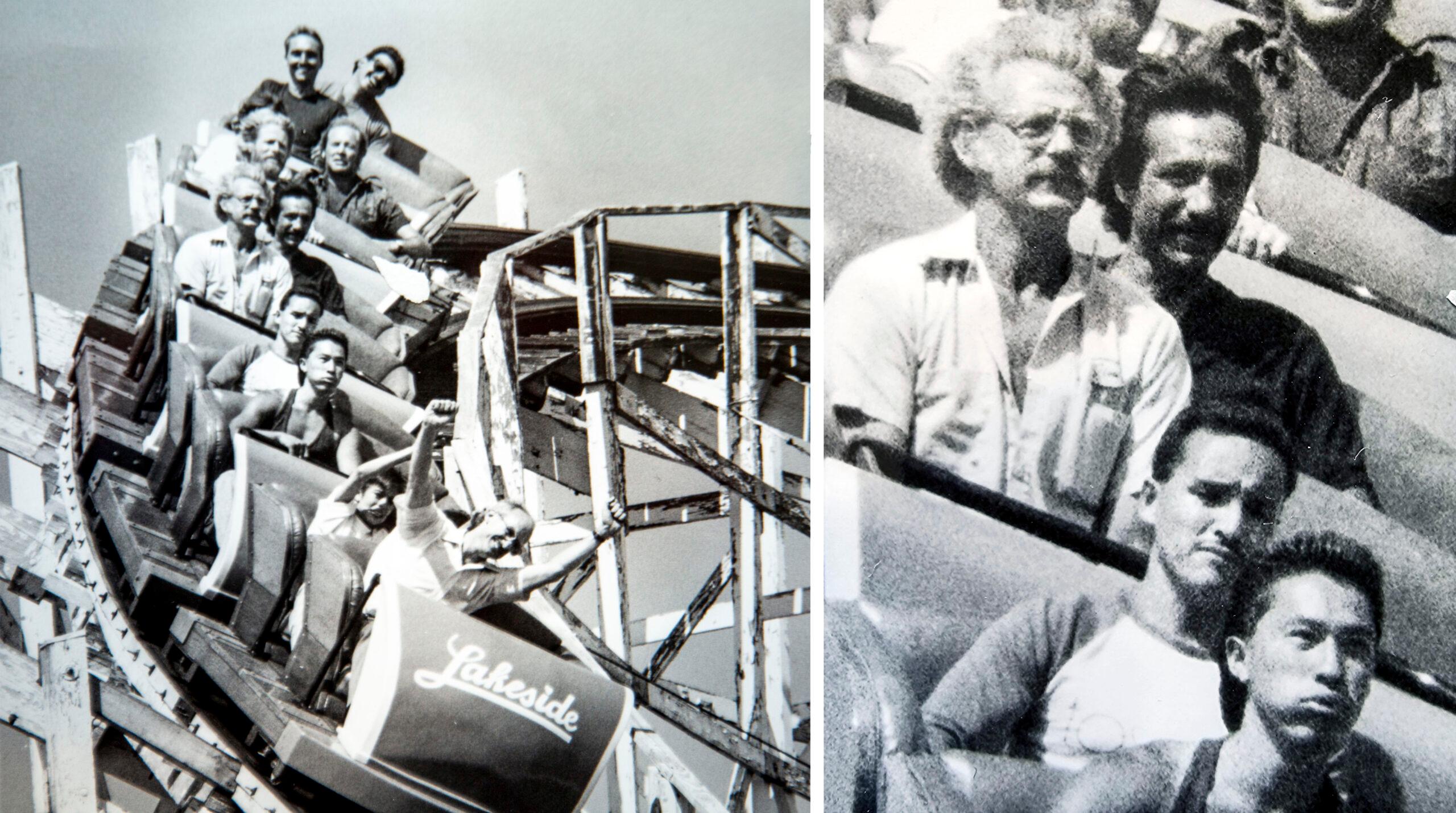

The majority of the Lakeside photos in DPL's archive come from the 1930s and clearly show this segregation. There are very few images that depict people of color having fun on the rides, even in those that are more recent.

Forsyth said Lakeside's ban on Black customers ended in the 1940s, when a lawsuit forced Elitch Gardens to change their policy. Lakeside soon followed suit.

The park evolved as the area around it changed.

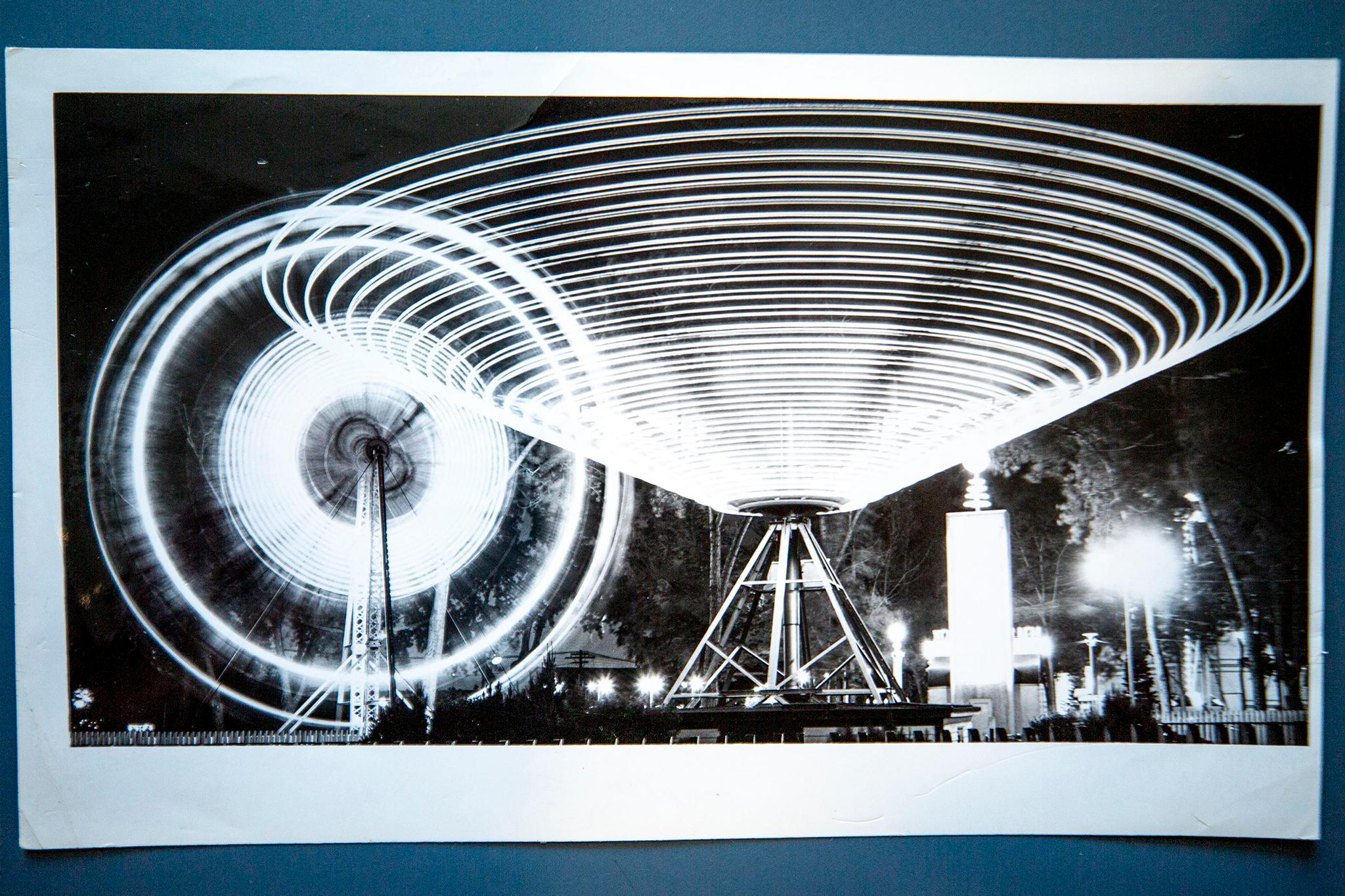

Some 5,000 amusement parks opened in the U.S. between 1895 and 1910. Five preceded Lakeside, but many closed over time.

"Only 100 of those parks still survived by 2008" nationwide, he wrote.

But Lakeside, he wrote, is "an amusement park that managed to survive every challenge thrown at it."

Lakeside even survived two pandemics: first the 1918 flu and, more recently, COVID-19. Though it couldn't open in 2020, the funnel cake and rides were ready for everybody in July 2021.

Correction: This story originally stated the Rocky Mountain News photo archive was rescued from a dumpster by a guy and his dog, Max. The "Max files" were actually images by Denver Post photographers.