In 2018, Denverites braced for a whole lot of construction. The I-70 expansion and 39th Avenue Greenway project were poised to begin, and the Globeville Landing revamp was already underway. All of these projects would turn up dirt in areas that were flush with soil pollution at one time, and sat in or near areas designated as Superfund sites by the EPA.

Back then, people who lived near these projects worried the digging could unleash heavy metals like lead and arsenic into the air, raining toxics onto their homes.

Gregg Thomas, head of the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment's Environmental Quality Division, said he and his colleagues knew people were unsettled by this possibility, so they decided to monitor the air to find out what would really happen.

"It looks nice in the end, but getting to that point obviously can cause some anxiety for people that live along the project," he told us. "That's really the intent of doing this work. We've heard these concerns."

DDPHE's work showed heavy metals didn't pour out of these construction sites.

Thomas and his team set up low-tech equipment around the three projects, which caught construction dust in fiber filters. They regularly collected the filters and sent them out to a lab, where the material was analyzed to find out what was contained in those particles.

Lead and arsenic are the biggest concerns at these sites, due to smelters in Elyria Swansea that operated from the late 1800s all the way until 1993. The facilities spit these metals into the air and down onto the neighborhood, eventually triggering an EPA Superfund designation. While the soil around most homes in the area was cleaned up, a lot of non-residential areas were not. It's a big reason why people were worried as these construction projects kicked off.

But Thomas said DDPHE's particle analysis during construction showed arsenic rarely rose high enough to detect, and that lead showed up at levels "orders of magnitude" lower than safe health standards.

The EPA's standards on chemicals in the air, including lead, are based on average exposure levels over a long period of time. Construction projects are considered short-term blips in air impacts, and they're not covered by the EPA's limits. Still, Thomas said he wanted to use EPA's standards as benchmarks to show whether the levels his analysis found were high or not.

While Thomas said residents were in the clear from toxics, he said he gets why people were worried.

"We still have brownfield sites, we still have Superfund sites in the city of Denver," he said. "You can imagine the concern about what's in the dust."

The analysis found the I-70 viaduct demolition did kick up plenty of regular dust.

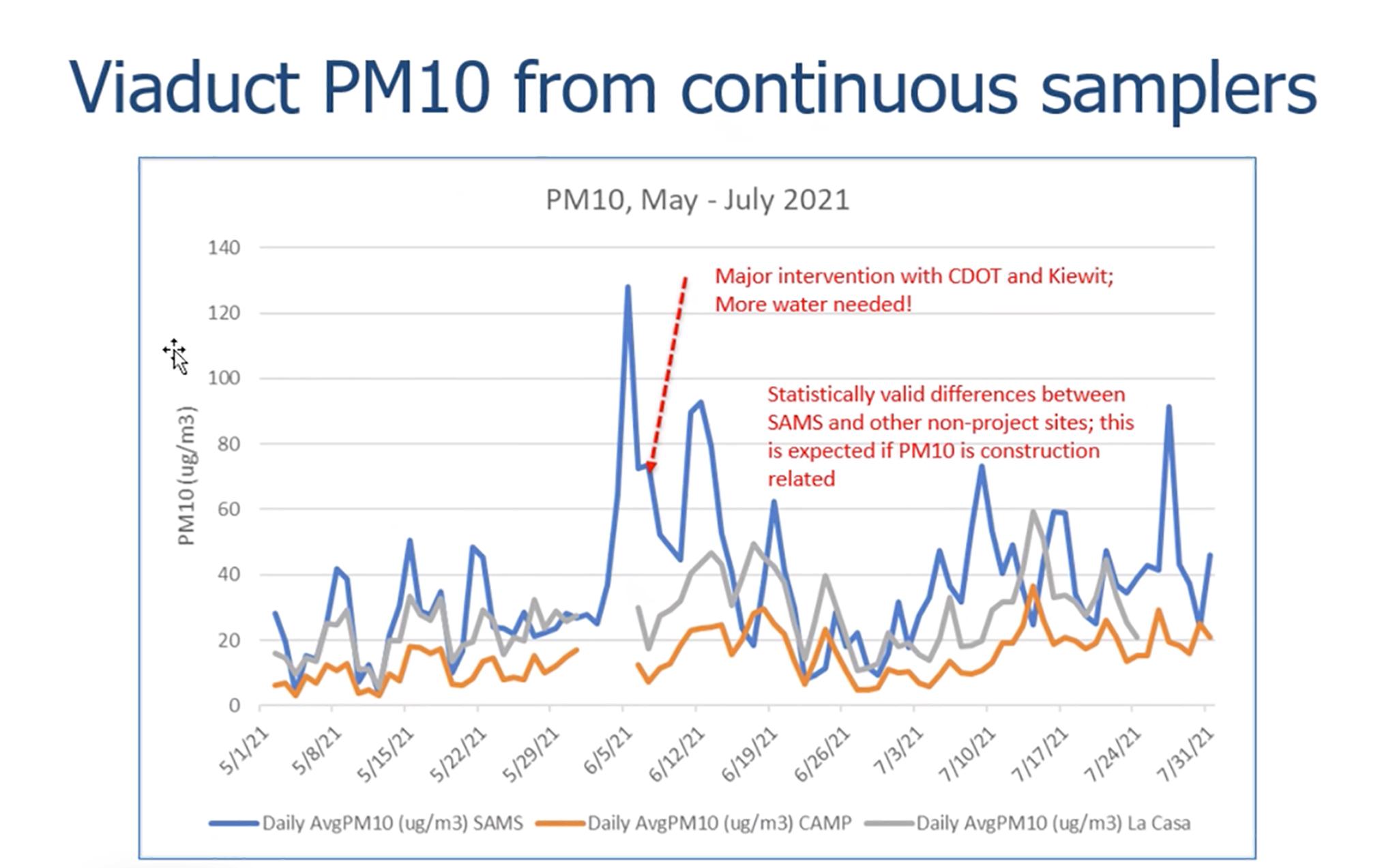

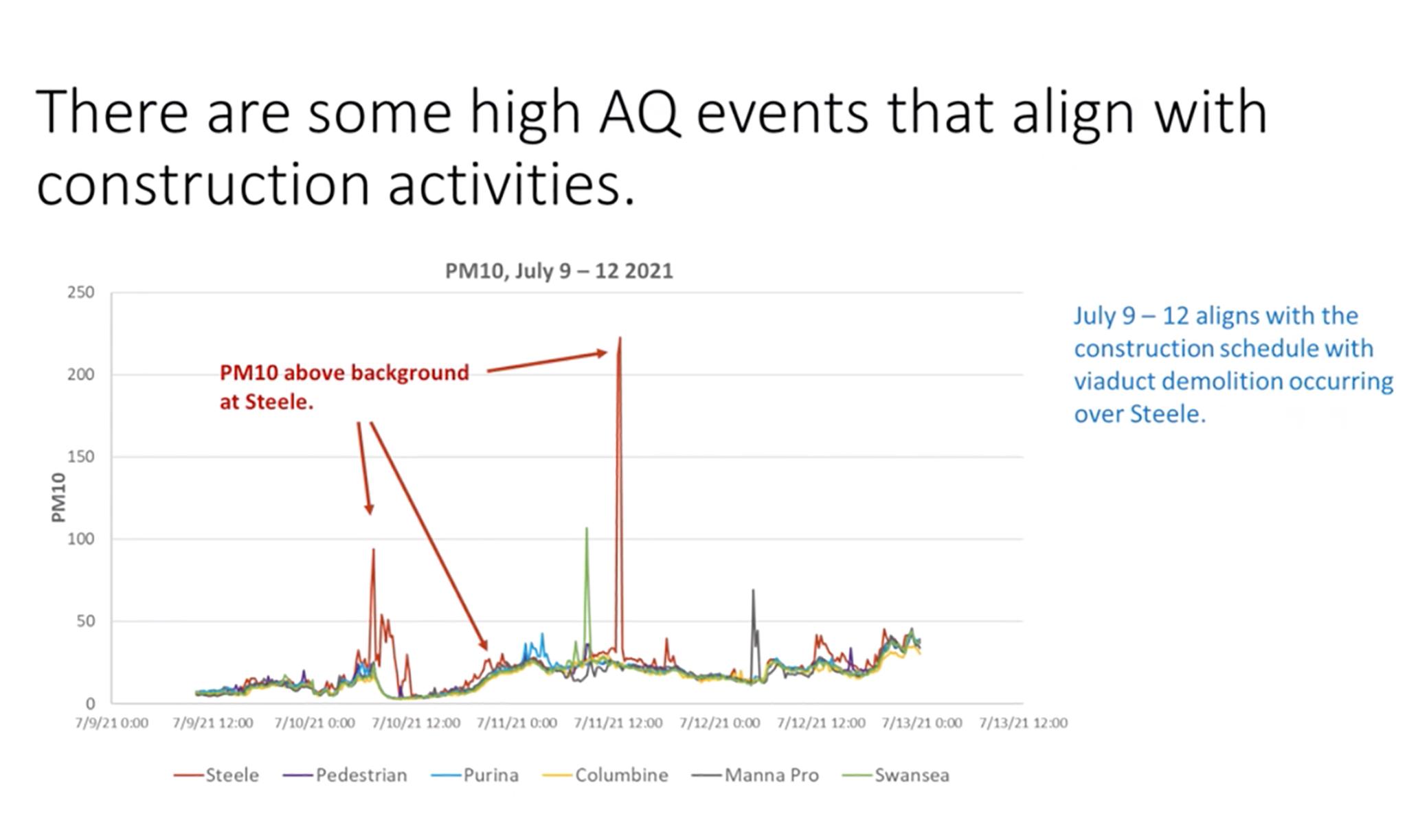

In addition to their filter monitors, Thomas' team also relied on data from a handful of real-time sensors set up near the highway. Altogether, the numbers showed CDOT and its contractor, Kiewit, did cause some dust-ups.

The biggest events took place between May 2021 and August 2021, when the hulking concrete viaduct was taken down. Thomas used data from elsewhere in the city to confirm that these spikes weren't due to larger sources, like wildfire smoke that blanketed the city.

His analysis showed spikes in PM10, particulate matter that measures up to ten microns in diameter, were more likely to show up during construction than PM2.5, which is smaller and more dangerous to the human body. Thomas told us DDPHE kept tabs on the continuous monitors during the demolition, and worked with CDOT during spikes to water down dust and keep it out of the air.

One big conclusion he drew from the study is that budgets for air quality on projects like these might be better spent on personnel, rather than more sensing. A city employee, he said, could be present and "always be on the lookout," be able to see if something looks wrong and make sure changes happen quickly.

The dust findings confirm what a lot of people in the neighborhood say they already knew intimately.

Diego Baron lives on Clayton Street, right next to the construction site. His home doesn't have air conditioning, so his windows were open for much of the summer when the viaduct was on its way down. All that dust made its way into his home, though he said he wasn't super bothered by it.

"It was just a little inconvenient. A little could come through the windows," he said. "It'd be really dirty."

Around the corner, Manuel Torres said he also dealt with dirt inside his home.

"We saw more dust all over," he said, including on his kitchen table.

Both men said the air has improved significantly since crews finished the viaduct demolition. Better yet, they both said, the neighborhood is way less noisy now that traffic has been lowered below where it previously traveled along I-70.

While Torres said the dust was a temporary annoyance, he said he has been worried about his son, who has asthma. The respiratory condition has long been prevalent in the neighborhood, and is likely related to the river of nearby traffic and heavy industry in the area.

In 2016, officials said lowering I-70 could decrease the amount of car-related pollution in the neighborhood, figuring that pollution particles could very easily float into homes from the old, raised viaduct. They also say cars are polluting less as fuel efficiency increases and more electric vehicles hit the road; but that trend is likely to bottom out. Thomas said DDPHE's next big project will put these ideas to the test: The agency started compiling air quality data before the highway renovation began, and they plan to see if anything changes in the years following its completion.