Fronzo Gilkey was briefly homeless when he lost his Park Hill home in the 2007 financial crash. The Navy veteran and retired postal worker said it was one of the lowest moments in his life, but he dug his way out and managed to restart things, in Green Valley Ranch.

The big house he purchased in 2013 represented a new era for him, but a conflict over an old Volkswagen is threatening his stability. In February, Gilkey's Home Owners Association, the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA, served him a court summons that alleged he broke neighborhood covenants by parking the yellow VW Bug on a concrete pad next to his garage. In a worst-case scenario, the HOA could foreclose on his home and eliminate every cent of equity he's invested into it.

Gilkey told us he's planning to fight the case. He said he never responded to a $1,400 fine issued by the HOA about the car, and also a washing machine he'd placed on the street for pickup, because he took moral issue with the charges.

"You don't start responding to things that you know is not right," he said.

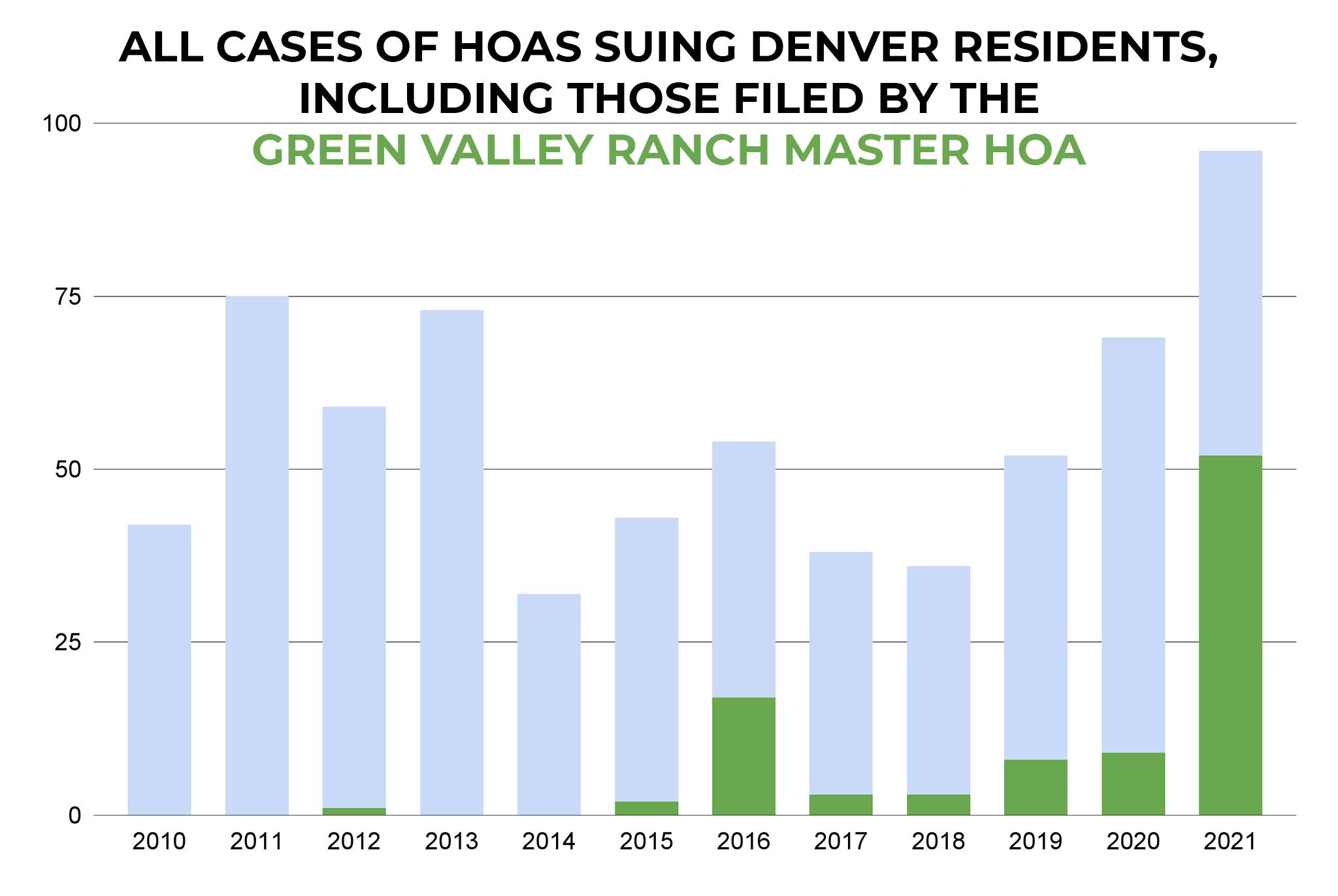

Gilkey's experience has become increasingly common in the far northeast neighborhood. Our analysis of court documents shows HOAs citywide took residents to court more in 2021 than any other year in the last decade, and that Gilkey's HOA was a major driver of this increase.

Here's what we found in the city's records:

The Denver Clerk and Recorder keeps copies of lis pendens, documents filed after any plea in a court case that relates to property. We ran a list of HOAs registered with Colorado's Department of Regulatory Agencies past those filings to extract cases involving these organizations, then reviewed each to ensure we were only looking at cases where HOAs were suing individual homeowners.

These conflicts typically begin with fines for broken neighborhood rules or missed payments on annual dues. When these situations aren't resolved, the HOAs can place a lien on the property in question, then take homeowners to court to move for a judicial foreclosure (which is different than a mortgage foreclosure). People like Gilkey, who have not yet gone to court or who paid fines to avoid going to court, do not show up in the lis pendens records we analyzed.

In 2021, 96 homeowners in Denver went to court in cases against their HOAs, the highest in our analysis of the data, which began at 2010. Fifty-two of these cases were brought by the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA.

Sabrina Allie, spokesperson with Denver's housing department, said that HOA approved at least 41 foreclosures in 2021 and 60 so far this year (three of which were in the city's affordable housing portfolio).

But most of these cases, she said, don't end up with people losing their homes. Most people who go to court end up paying what they owe. People who can't afford to pay the fine often have lenders who pay off their liens, and they refinance their mortgages.

Here's what we know about why this is happening:

None of the Green Valley Master HOA's board members responded to requests for comment for this story. We actually found Gilkey because he was a delegate to the board for his area in the neighborhood, but he didn't have any insight into why the HOA has brought so many people to court.

Eric Gravenson, who has been involved with various aspects of the Green Valley Master HOA for 25 years, told us none of the recent cases are likely related to missed annual dues. In 2007, members of the HOA voted to allow the Green Valley Ranch Metropolitan District, a quasi-governmental organization, to collect dues through annual property taxes. The vote also turned the metro district into a "contractor" that would handle all issues related to covenant violations, fines and collections. He said it's one of the only such configurations in the state. Both organizations are led by residents.

Micaela Duffy, who heads the metro district and signs the legal complaints that result in court summons, said she couldn't speak to us because the HOA did not approve it. But Jose Vasquez, a lawyer who works with Colorado Legal Services, a nonprofit advocacy group, told us the uptick may be related to COVID-19. While Colorado imposed a moratorium on foreclosures during the pandemic in response to the sudden economic downturn, protections were not applied to the kind of "judicial foreclosures" that happen in legal fights with HOAs.

"There isn't any such mechanism with the homeowners association, so the same people who are falling behind on their mortgages are probably falling behind on their HOA fees, too," Vasquez told us. "There is no relief that I'm aware of."

Likewise, city programs that offer money for mortgage relief also do not apply to HOA fees and fines. Allie, with Denver's housing department, said the city can help with legal services.

Still, Vasquez said people who are taken to court have very little recourse. Homeowners sign contracts with HOAs that give them enormous power to enforce their rules, and there's not much he can tell someone who lost work or became disabled and can no longer keep up with fines and dues.

"What happens if you don't agree with the amount that they're charging?" he said. "Unless we have a super strong case, unless we're sure we're going to prevail, chances are I'm going to turn to my clients and say, 'You better think about settling.'"

But settling can be very expensive, as fees can rack up quickly. One Green Valley Ranch Master HOA resident we spoke to shared documents that showed violations related to drainage he installed by his driveway and an AC unit in his window ended up costing him over $16,000 after he refused to pay up over the course of a decade. Gilkey said he knows a lot of neighbors who have dealt with fines.

"The message is: If you don't pay this, this is going to increase and it will lead to foreclosure," Vasquez said. "There's nothing in our statute that limits the amount of fees, the amount of costs. In essence, there's very little regulation."

A state bill under consideration would limit some of these fees. In the meantime, Denver officials say they're mobilizing to address what's happening in Green Valley Ranch.

Last month, State House Rep. Naquetta Ricks of Arapahoe County introduced a measure that attempts to curb HOAs' ability to ramp up late fees. The bill, titled "Homeowners' Association Board Accountability And Transparency," would require HOAs to offer repayment plans to residents who otherwise may face foreclosure and prohibits them from collecting fees "for the purpose of generating revenue."

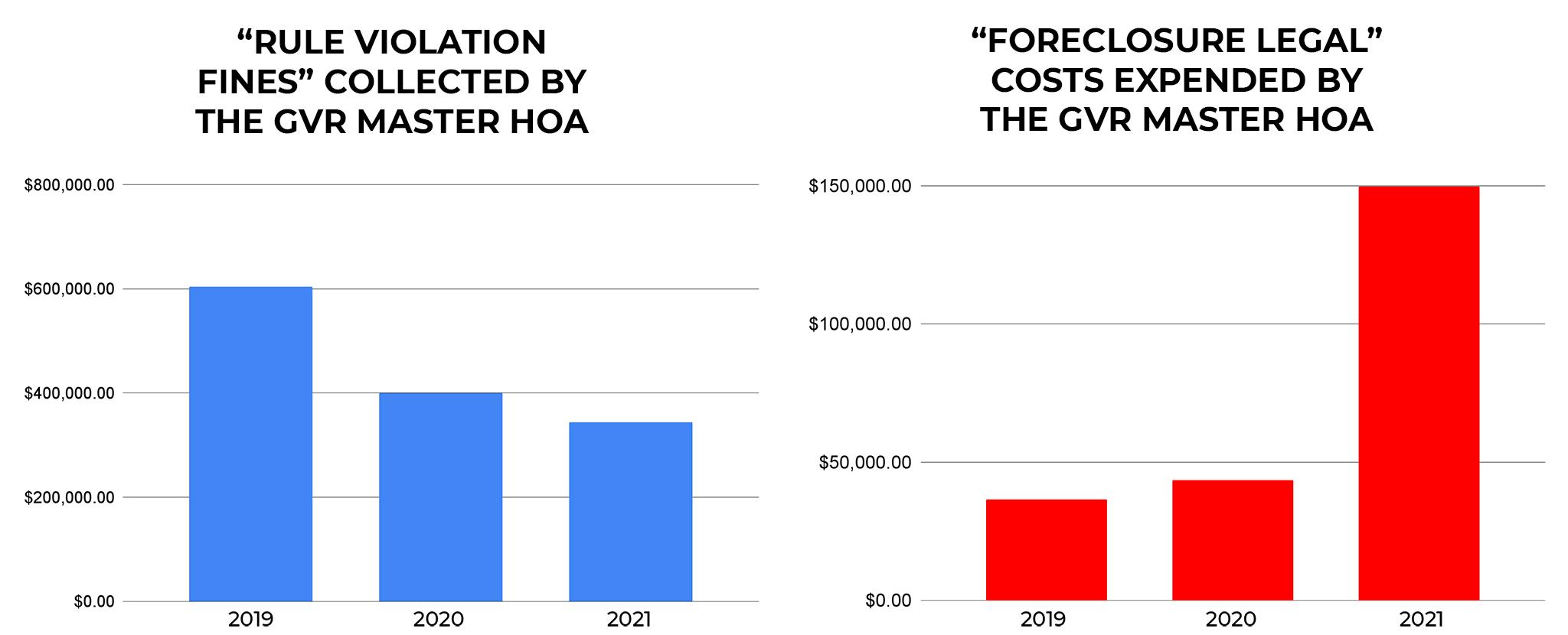

In 2019, the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA generated over $600,000 in "income" from late fees, but that number dropped after the pandemic arrived. They collected almost $350,000 in fines in 2021 - but their spending on "foreclosure legal" fees jumped. In 2020, the HOA recorded spending $43,000 on foreclosure proceedings. In between January and November 2021, that figure had risen to $149,000.

Denver City Councilmember Stacie Gilmore, who presides over the city's far northeast neighborhoods, said she was "concerned" when she saw our initial analysis of HOA-related lawsuits.

"When we think of keeping our residents housed during these challenging times, HOA fees and violations are another added variable to that struggle," she told us.

In learning about the broader trends, and after housing advocates told her about a family who didn't know their home was sold at auction until they were kicked out, Gilmore raised the issue to the Denver Department of Housing Stability. The department is now working to connect people facing foreclosure with nonprofits who might be able to help them keep their homes.

Gilmore will also hold a town hall on March 12 from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the Green Valley Ranch Rec. Center to explain the foreclosure process and resources available to "homeowners facing financial distress," she said.

Unless he decides to pay his fines, Fronzo Gilkey will go to court in April.