If all goes according to plan, one of Denver's most prolific LGBTQ bars - and the community that grew within it - will get big-screen treatment.

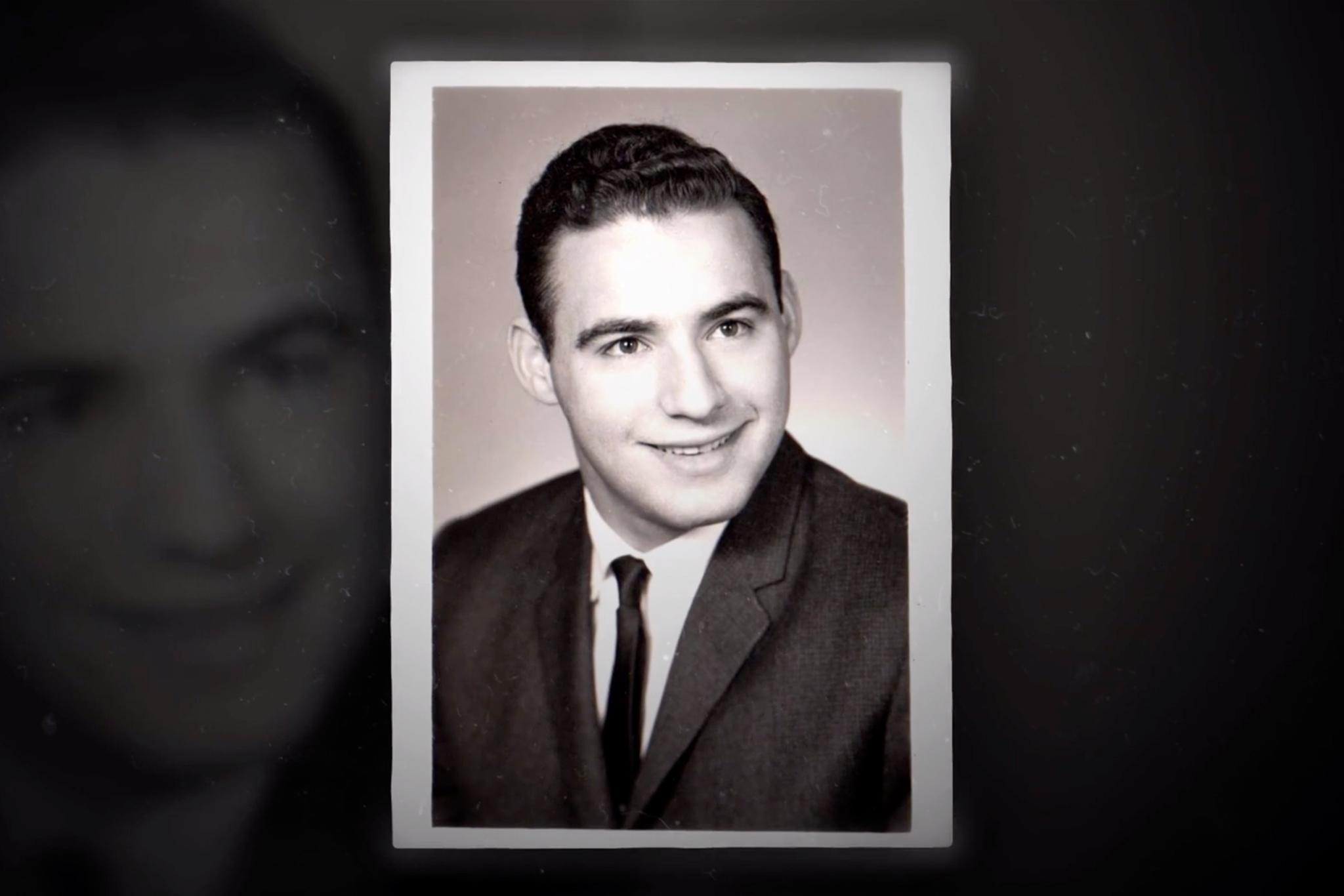

"Making Tracks" is the brainchild of local filmmaker Shawna Schultz. She began writing her script in 2019 after her production company, Mass FX Media, was hired to make a memorial video about Marty Chernoff, Tracks' longtime owner, who died that year. As she interviewed Chernoff's friends and former employees, she developed a sense that the story of his club, and the people who made it successful, needed to be told in a bigger way.

She started with a short documentary about Chernoff that was picked up by Rocky Mountain PBS, then got to work on a more Hollywood version of the story.

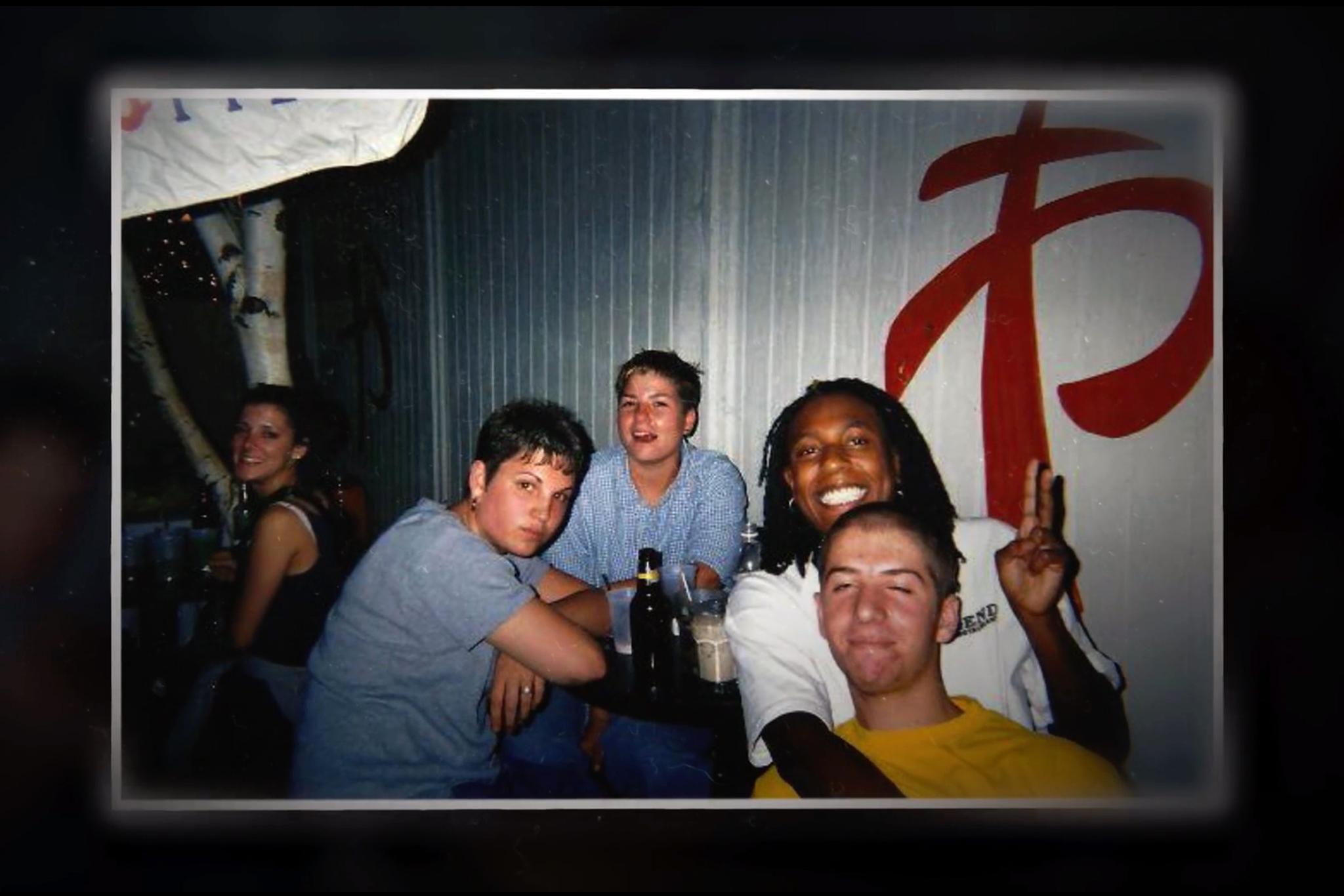

Schultz's script centers around a character named Ricky, a teenager whose parents kicked him out of their home when he came out as gay. Ricky finds his way to Tracks when he arrives in Denver without much but the clothes on his back. There, he discovers a community and a place to belong.

Schultz said Ricky and the rest of her characters are composites of Denver's and Tracks' real histories, gathered through interviews and historic documents. She said Mass FX Media and partners Listen Productions have raised about half of the $4 million they need to begin production. They're planning to film most of the movie in Denver.

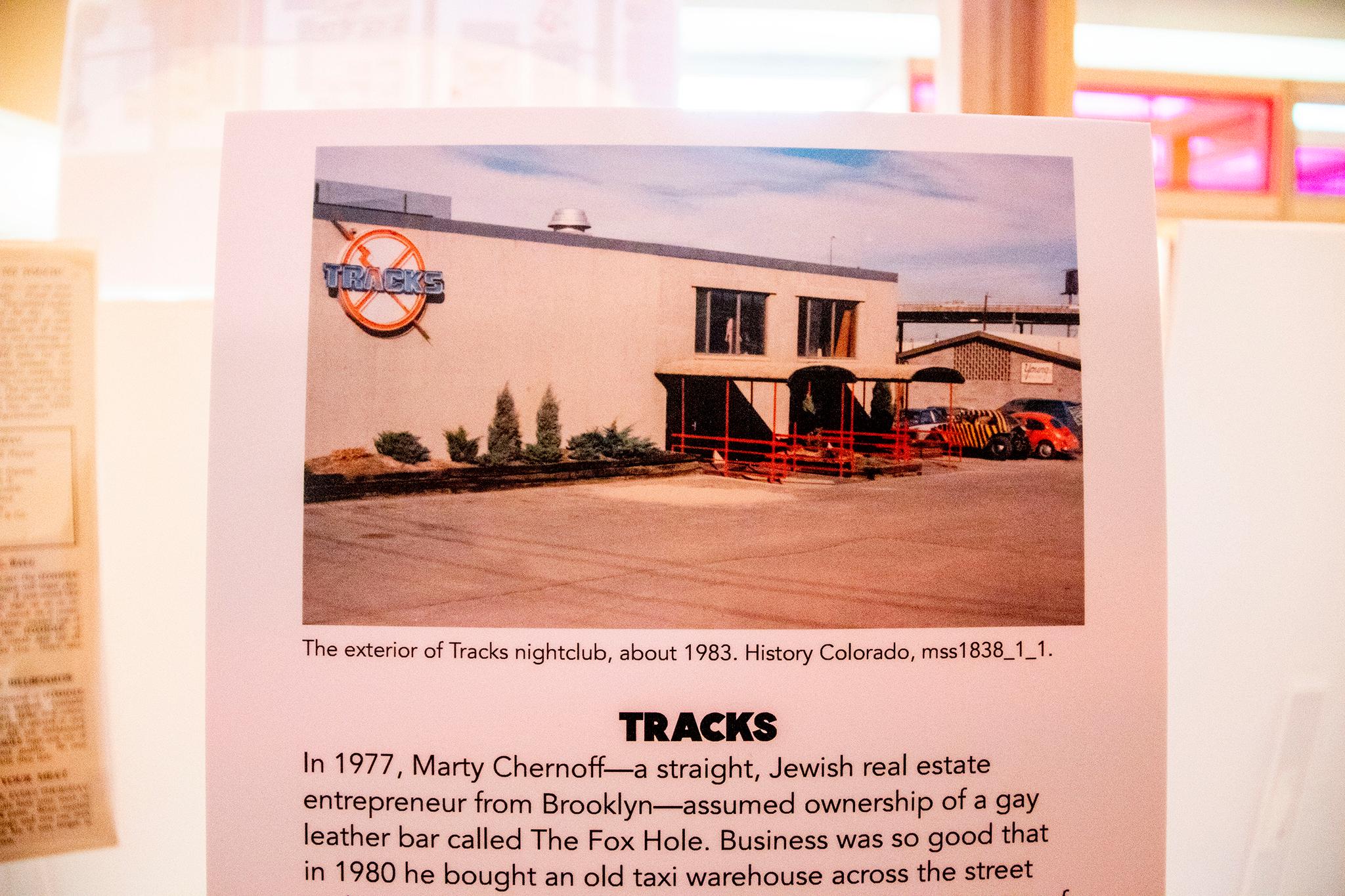

Denver looked different when Tracks opened behind Union Station in the early '80s.

The neighborhood, known then as "the bottoms," was years away from redevelopment. Aaron Marcus, History Colorado's LBGTQ curator, remembers his first visit.

"You had to take 15th and go down this weird dirt road to get there," he remembered, laughing. "I'm like, am I gonna end up dead?"

When Chernoff was still an up-and-coming entrepreneur, he bought a gay bar called the Fox Hole in the area between Union Station and the South Platte River. When he realized nightlife could be good business, he purchased an old taxi warehouse across the street and called it Tracks.

Though it was surrounded by neglected infrastructure, Marcus said it was cutting-edge inside. Tracks had the best music and sound systems, and it was one of the only gay bars in town that offered a true dance scene. It quickly became a major centerpiece in Denver's LGBTQ community.

Tracks, he added, has had an unusually long lifespan for a LGBTQ bar. While lesbian bars have seen a particularly high rate of closure in recent decades, he said the romantic matchmaking and activist planning that allowed these businesses to thrive have moved online and made it harder for any such venture to survive.

It wasn't just the music that so endeared Tracks to patrons.

It became a place of refuge for many gay people who were ousted from their families and mainstream society. It was a home in more than a figurative sense: Schultz said Chernoff was known to keep cots in the back for employees and guests who had nowhere else to go. Ricky's fictional character draws from interviews with several real people who landed at the club after they became homeless.

"Marty created a place for them to live," Shultz said.

While most of her characters are fictionalized, Chernoff is a character in Schultz's script, someone she could not leave out of the film. She said she was drawn to him because he occupied an unusual position in Denver's gay culture. He was straight, Jewish and always described himself as "a businessman not an activist." And yet, Schultz said he was an ally and a champion of a community that was still years away from broad acceptance in the city. She told us she worked for a year to convince Chernoff's family to green-light a movie about him.

Every good story needs a villain.

Homophobia is ever present in Schultz's script. It appears in Ricky's relationship with his family and Chernoff's struggle to build Tracks and keep it open. But Schultz said it was difficult to distill those conflicts into a single character.

"We needed the antagonist. So who is the bad guy? That was a big struggle," she said. "Ultimately, we landed on the City Council."

In her interviews, she heard stories that certain Council members were uncomfortable with LGBTQ culture and used procedural roadblocks, like gummed-up permitting and construction approvals, to keep Tracks from ever opening. But Chernoff was creative and found ways to keep his business going.

"He always figured out a way for it to be a win-win. OK, we can't open on time? Well what are we going to do? Our opening night will be a construction-themed party," she said, invoking Chernoff's resolve. "They went ahead and just did the opening anyway, and they gave everyone hard hats and people loved it."

Though the movie takes plenty of artistic liberties to mash 25 years of history into two hours, the construction hat story is true. And there was plenty precedent to make City Council the "bad guy."

Even before Chernoff began working on Tracks, conflict between LBGTQ activists and Council had boiled over in a very public way. In 1973, History Colorado's Aaron Marcus said more than 300 people surged into a Council meeting demanding they overturn four anti-gay laws that allowed police to arrest people for "crossdressing" and entrap men looking for sex, then throw them in jail. After hours of testimony that stretched late into the night, Council agreed to repeal the ordinances. Marcus said it was "Denver's Stonewall moment."

There's another big antagonist lurking in Schultz's script: the AIDS epidemic.

The American public became aware of AIDS and HIV in the 1980s, and it was quickly thought of as a disease transmitted between gay men. Heavy stigma was soon to follow. It took President Ronald Reagan four years to publicly acknowledge the epidemic.

Before the AIDS crisis, Chernoff was riding high on Tracks' business success. Schultz said he had plans to open new franchises in major cities and even take his company public. Though he did open one branch in Washington, D.C., the rest of his plans fell through when the virus took over.

In her research, Schultz learned that Chernoff was quick to support his employees when the epidemic threw their lives and community into chaos. He paid for viral testing at the club, one of the few places in the city where people could access that kind of care. Schultz said he also paid hospital bills for people who fell ill.

The movie script follows Chernoff, Ricky and the nightclub into this dark time. It was a pivotal moment that tested the real people who orbited around Tracks in the 1980s and '90s, and important context for her (mostly) fictional characters. While real-life Denverites suffered enormous loss during that time, Schultz said the way they rose to meet the moment was a major reason she decided to write "Making Tracks."

"During the AIDS crisis, people in the gay community, the LGBT community, were so ostracized," she said. "This is the story of a time where people were unsafe in public to be exactly themselves. And here, this place, was opened by a person who was the most unlikely person to pursue this and make a home for those people. I think it's finding home, finding belonging. Those are things that just resonate, no matter who you are."

Schultz will direct the picture, her first feature narrative. Screenwriter Stephen Beer worked on the script. It's being produced by Schultz, Marin Lepore, Anthony Morgan and Mitch Dickman. Andrew Feinstein, who currently owns Tracks and was a business partner of Marty Chernoff, is an executive producer.