Not everyone is down to tube the South Platte River. The water has long hosted harmful E. coli, especially close to Denver's core, which has defied Mayor Hancock's circa-2013 goal to make the river "swimmable."

Still, there are plenty of us who have discovered the distinct joy of floating portions of the Platte further upstream, from the Chatfield Reservoir to Breckenridge Brewery's massive complex in Littleton. The cold water and lazy-river vibe can be very nice on a hot summer day. Sometimes, the hour-ish route brings you past baby ducks!

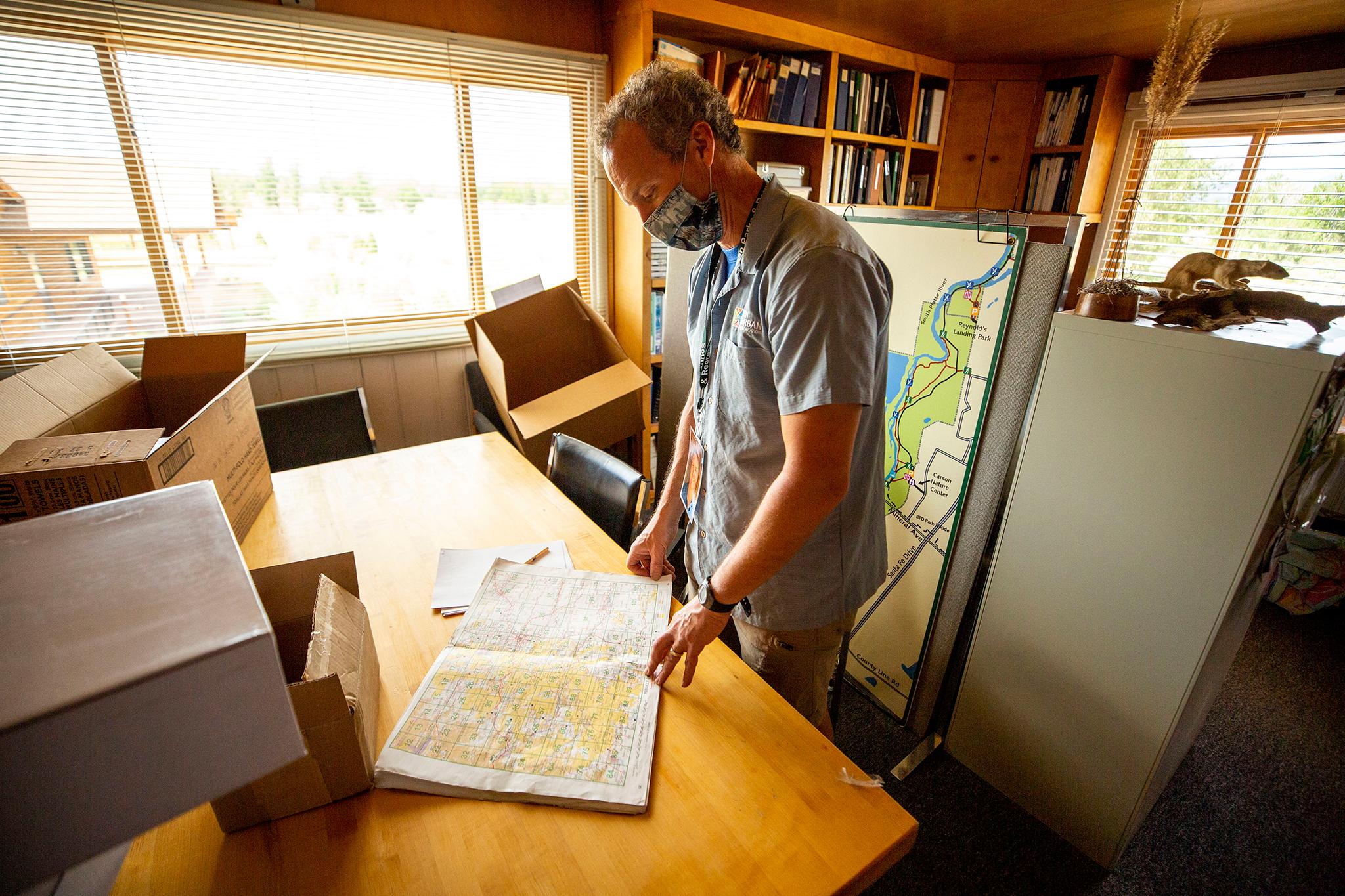

But the debate over whether you should take the plunge is probably moot in 2022. Each year, we check in with South Platte Park boss Skot Latona (who has been called a real-life Leslie Knope) to get a tubing report.

"This summer, things are low as may be expected, based on our snowpack," he told us.

In other words, there isn't enough water to make the float. Colorado is dry enough that there's already been an "emergency" prohibition on fishing near Steamboat and wildfire authorities are wringing their hands over the possibility of more big blazes.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Experts expect climate change will eventually make Colorado resemble present-day Arizona, and we're likely already seeing the beginning of that shift. Despite decent conditions circa 2017, the Platte has been more hostile than not to tubers in recent years. Levels have been low enough that Latona's started collecting the carcasses of tubes popped on rocks and to hang at the park as warning signs for anyone who might want to send it.

Generally, it's safe to tube if streamflow gauges register between 100 and 500 cubic feet per second on the river. Latona's segment of the Platte saw three days with acceptable levels since the start of June. He said that probably won't happen again this year. (You can check the streamflow on the state's website.)

State officials are trying to release more water into the river to protect wildlife, but that hasn't happened yet.

South Platte water levels are not directly influenced by snowpack and flows from the mountains. Instead, water streams from sources southwest of Denver into the Chatfield Reservoir, where it's held and released on very specific schedules based on the needs of people downstream. A farmer in the eastern plains with rights to that water, for example, might call the state authority and ask for a release; the state lets a specific amount out from the dam and the farmer is allowed to divert that quantity to her crops.

In a dry year, there must be enough of these releases at once to facilitate good tubing conditions. In years when there's a water surplus, the state lets excesses flow through, ensuring better conditions for floating.

In 2020, the state completed a revamp on Chatfield's reservoir, which expanded its capacity and made room for a special "environmental pool." This water is meant to trickle through the South Platte when there otherwise won't be enough releases to support habitats through Denver and Littleton. It may not be enough for tubing, but it would keep the river from getting dangerously low for plants and animals.

But Jason Clay, a spokesperson with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, told us the state hasn't been able to use the environmental pool yet because they haven't secured the necessary supply to actually allocate that water. Water rights are complicated, but basically: governments or people with older, or more senior, rights get first dibs on moisture, and everyone else needs to wait their turn. If there's not enough water for everyone, owners of the most junior rights are out of luck.

While Clay said Colorado does have some rights secured for the environmental pool, they're so far down the priority list that they haven't been able to actually use them in the dry years since the Chatfield renovation was completed. He told us his department is working on acquiring more senior rights that might let them make these wildlife releases when they need them.

Meanwhile, Skot Latona is thinning out thirsty trees.

As the state figures out how to keep the Platte wet, Latona said his team has been working to make South Platte Park less thirsty.

The park is full of cottonwoods that originally thrived in the area because of seasonal flooding, which once ravaged early Denver. The Chatfield Reservoir was built, in part, to stop these floods from messing with our built environment. Now that things are drying out, the cottonwoods are far less viable in Latona's ecosystem and a burden on the park's limited water supply.

"We're looking into what it would take to shift this forest into something that would survive on lower water," he told us, "probably reduce the number of trees."

For now, his team at South Platte Park isn't spending much energy to revive damaged or dying cottonwoods.

Latona said tree removal might become more common in the Front Range in general. If you stand on Dinosaur Ridge and look over the metro, you'll see a lot of green canopy that was never part of the ecosystem here. One hundred years ago, he said, "it would have been a shortgrass prairies with a ribbon of trees running though it" along the river. Our water pressures might force us to return to the way things were - before the changing climate moves things into new, unknown territory.