Erin Espelie has found comfort in the microscopic. A biologist turned filmmaker, she's long been interested in using art to talk about environmental issues and the way climate change is reshaping our world.

But she began to feel that focusing her lens on humans, and even animals, placed her too close to ethical quagmires she wanted to avoid. There's been a lot of discussion lately about photography's role in empire-building, the ways it can skew reality and perpetuate stereotypes, especially when it comes to people who've already been pushed to society's margins. She realized it's impossible to observe someone without impacting them.

"I certainly don't want to be a parachute journalist or documentarian, and go in and tell someone else's stories for them," she told us.

So instead, she's been diving into tinier worlds, bringing microscopic environmental stories to human scale. A collection of her work is on display in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science's Expedition Health exhibit.

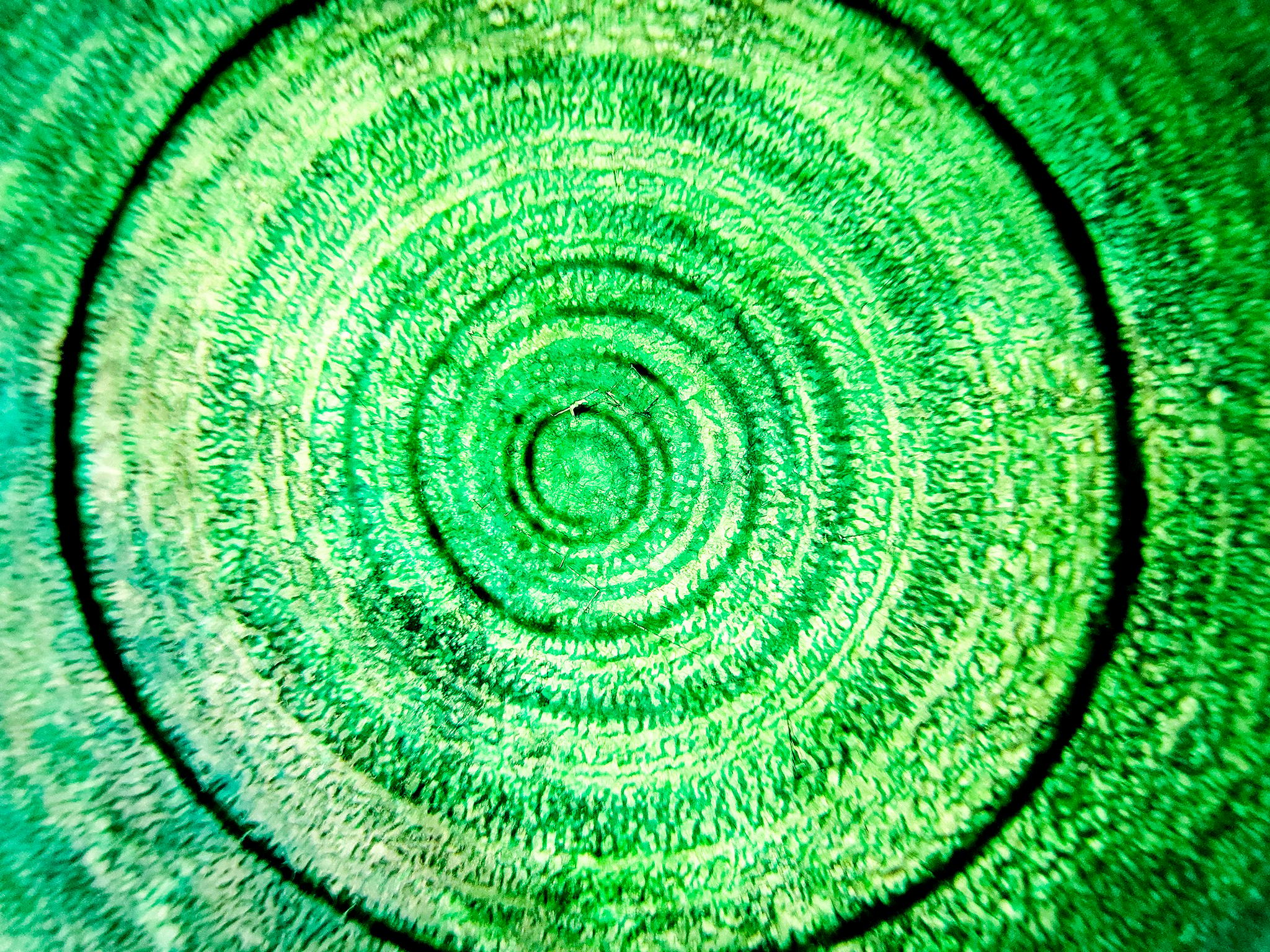

"REFRESH" centers around time-lapse video she created in a University of Colorado Boulder microbe lab, where she's an artist in residence. The video shows generations of cyanobacteria feeding on light, growing, multiplying and then killing itself with the oxygen it produces through photosynthesis.

One wall next to the screen features photographs of the bacteria. On another are dozens of petri dishes containing artfully "plated" specimens that, like the organisms onscreen, are slowly chewing up light and giving birth to new progeny.

Cyanobacteria offers a bit of hope amid our climate crisis.

Espelie met researcher Jeff Cameron a few years ago, through a program meant to connect University of Colorado faculty who work in different departments and otherwise may never interact. He was an artist who found a career in science. She was a scientist who'd immersed herself in arts.

"Immediately, it was a connection between the two of us," Cameron recalled.

Cameron studies cyanobacteria, the stuff that can spawn algae blooms in Denver's lakes. While climate change is poised to make these blooms more common, Cameron and Espelie are both fascinated with the bacteria's potential to pull us from the brink of climate crisis.

Cyanobacteria contain an organelle called a carboxysome, which plucks carbon dioxide molecules out of the air and turns it into energy, emitting oxygen as a byproduct. About 4.5 billion years ago, the tiny organisms chewed up so much carbon and sunlight and spat out so much oxygen, they made Earth habitable for animals like us.

"We owe a great debt to these creatures," Espelie told us. "Cyanobacteria are capable of doing all of the things we need at the moment, which is sequestering CO2 and producing more oxygen."

Cameron's research is about understanding that carbon-fixing mechanism and finding ways to use it to reverse some of the damage our species has wrought on the environment. Work like this has already led to a new kind of building material, "bio-cement," which is grown with bacteria into cinderblocks and skips the intense emissions that come with making regular cement. Cameron said scientists are also thinking about how to use cyanobacteria's talents to "supercharge" plants' ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

The project shows how art and science can be symbiotic, feeding into each other.

It didn't take long for Espelie to find beauty in Cameron's research when she joined his lab. The bacteria grew in vibrant shades of green and blue and sometimes brown. She found she could paint spores onto petri dishes, or let them spiral out on centrifuges, so the organisms would grow in artistic patterns.

She found them attractive and poignant. They could help save us, but they also resembled us.

"They too will self-destruct if they create too much of their byproduct," she said. The oxygen they produced grew into bubbles that suffocated them. "I can't overemphasize how beautiful I think they are. And there's something about the way that they move that I think could also be really useful to us in this moment."

Time-lapse was the key to unlocking that movement. It could speed up the cyanobacteria's lifecycle so dozens of generations would grow, multiply and die onscreen in a matter of minutes.

"I find them meditative," Espelie told us. "They take you to a different sense of time and space."

In pursuing her art, Espelie also unlocked new research pathways for Cameron.

"Doing the films has really kind of opened up our eyes to the diversity of cyanobacteria and the different ways they grow," Cameron said. "A lot of our new projects have spawned from the visuals."

To him, the footage is raw data used in scientific research papers. Their process has also charted new cinematographic territory. They had to develop a novel camera system that could shoot time-lapse on a microscopic scale; lighting built into the system simultaneously made exposure possible and fed the bacteria over its multiple lifespans.

For Espelie, seeing art feed back into research is a dream.

"That, as an artist who is at heart a scientist, is my ultimate holy grail," she said. "This is what I believe science and art can do when engaged in a way that's meaningful."

REFRESH will be open for a few more months, a spokesperson for DMNS told us. In addition to new art and research through CU's NEST Studio for the Arts, Espelie plans to produce a longer narrative piece around her bacterial footage. You can check out some of her past work on mealworms from the Rocky Mountain Micro Ranch here: