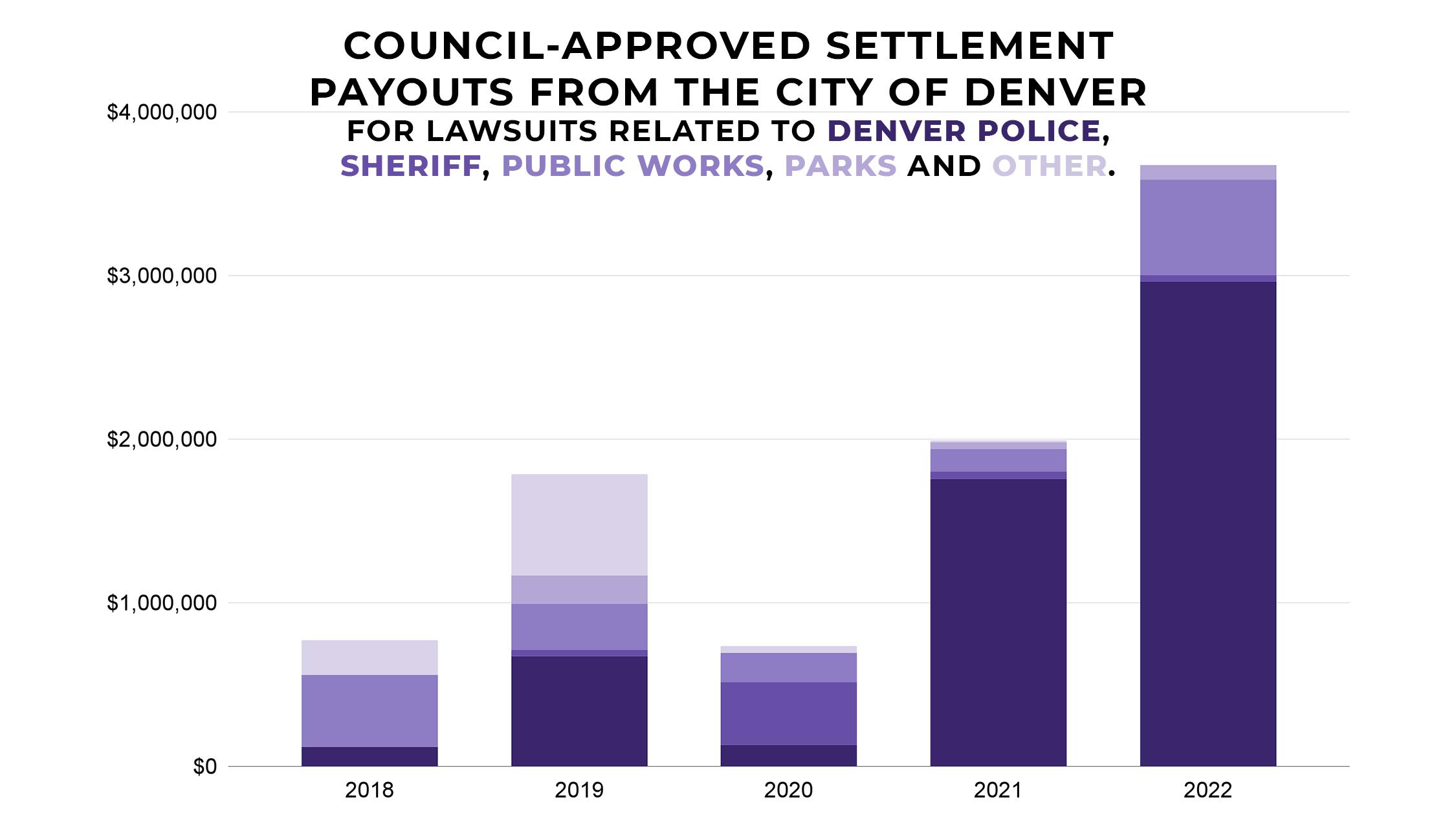

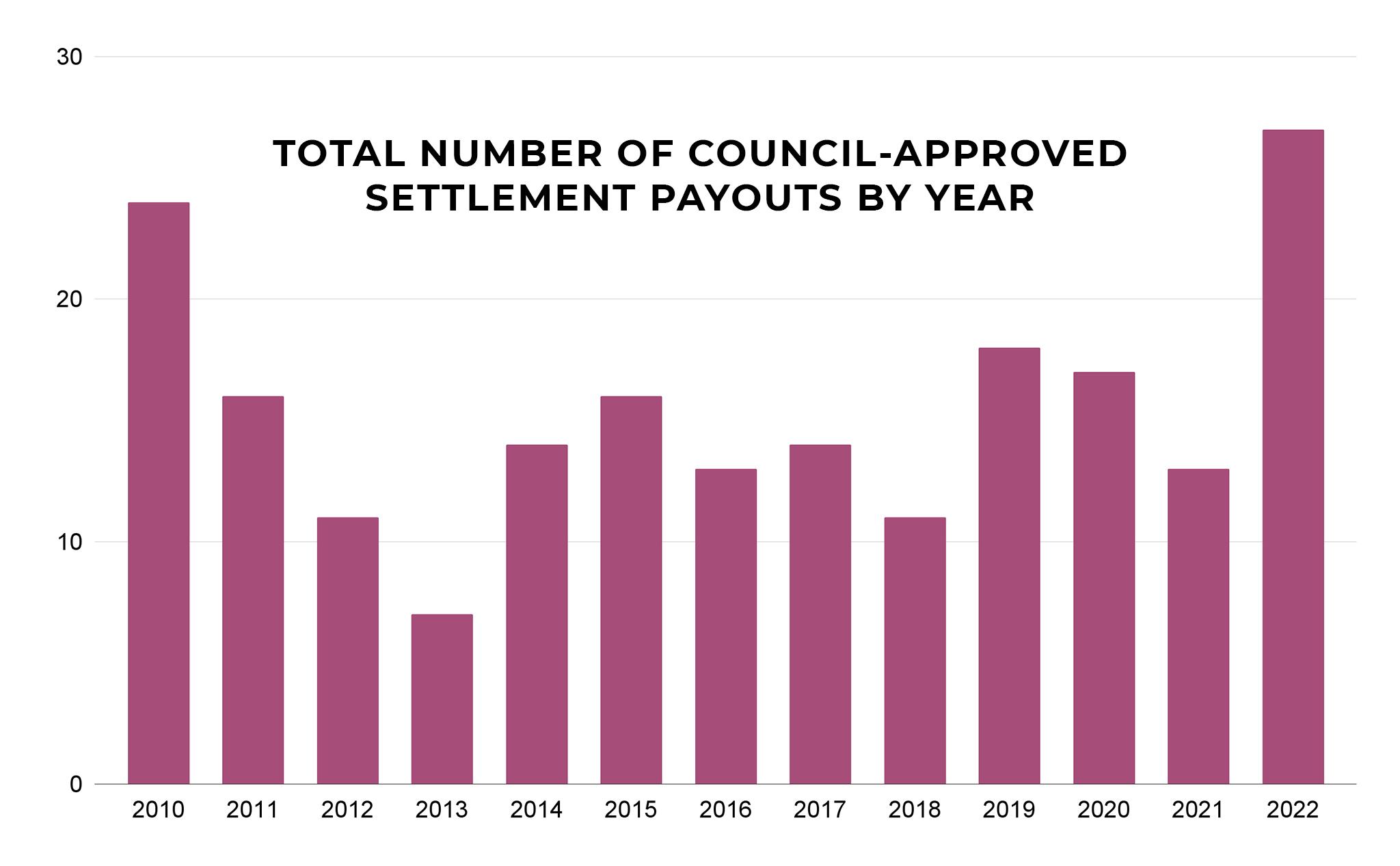

Lawsuits regarding Denver Police officers' behavior have cost the City and County of Denver almost $3 million so far in 2022 -- a significant rise in the last five years and the third-highest figure since 2010, according to data provided by the City Attorney's office. This year also represents the largest quantity of payouts in a decade, thanks to a spate of lawsuits filed by people who claimed they were injured by police during the large George Floyd protests in 2020.

The data only includes payouts that were over $5,000 and therefore required approval from City Council. The City Attorney's office said it doesn't keep detailed spreadsheets of settlements below that threshold.

This does not include money Denver was required to pay from complaints that went to trial, like the $14 million a jury awarded to protesters last March.

Source: Denver City Attorney's Office

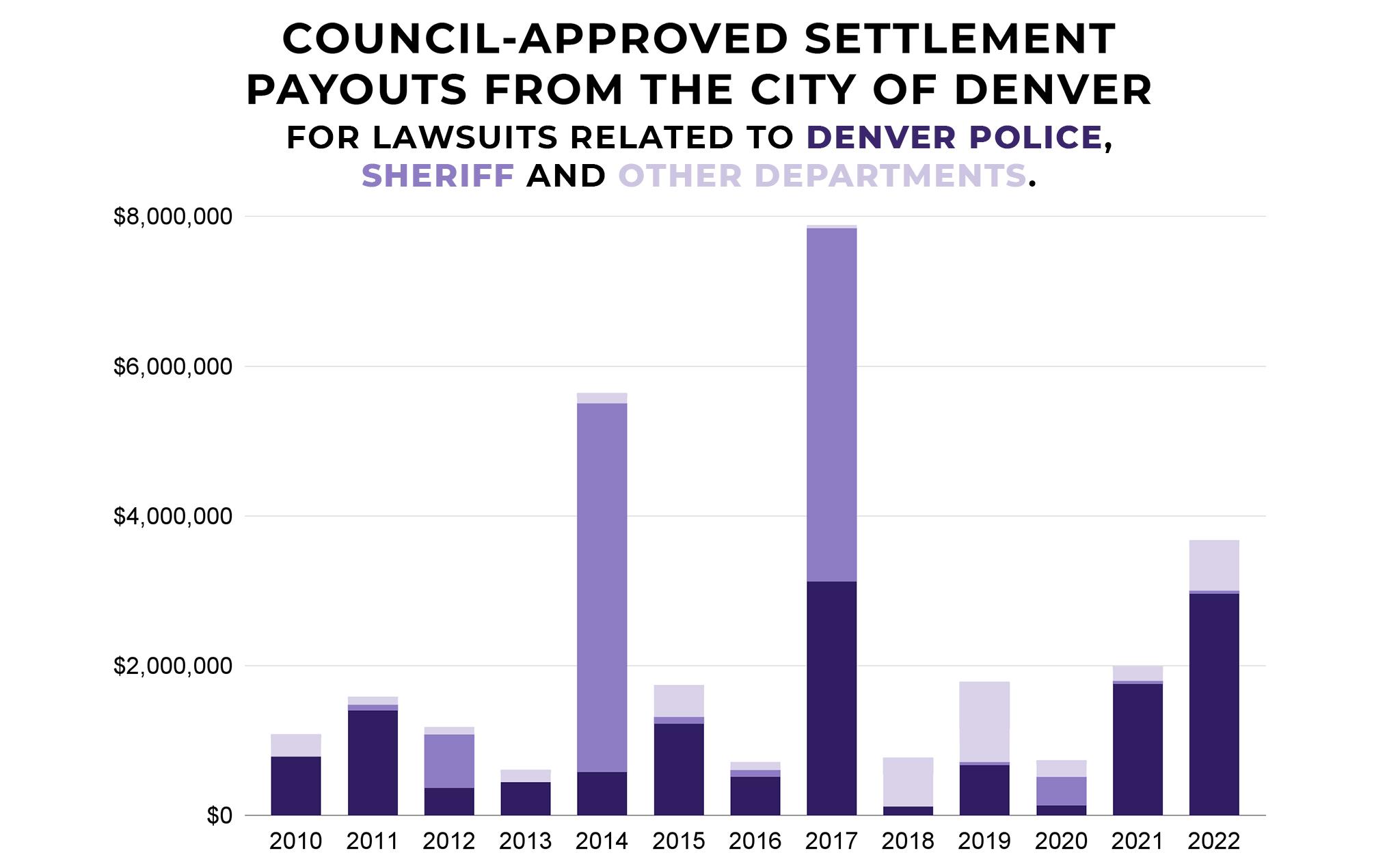

While 2022's figures are at a high since 2018, the year Chief Paul Pazen was sworn into office, the total dollars spent this year was still lower than 2017 and 2014, when public cases like the deaths of Michael Marshall, Jessica Hernandez and beatings of Jamal Hunter and Alex Landau generated some of the largest settlements in Denver's history.

Source: Denver City Attorney's Office

Denver paid out an average of $1 million on police-related settlements since 2010, on par with Boston, Memphis and Atlanta but far below New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C.

Mari Newman, a partner with the law firm Killmer, Lane and Newman, said settlements with Denver are usually "very long and deliberate" processes that involve third-party mediators.

Cities tend to go through cycles in the ways they deal with lawsuits, she added. Administrations usually act "tough" and try to fight claims in court when they've first arrived in office, then opt for settlements down the line, usually after they've lost a case or two.

Newman said the trial in March probably demonstrated that juries "have had it with police brutality" and signaled there's too much financial risk to let any more protester complaints go to court. She told us something similar played out in 2014, when Mayor Michael Hancock's administration fought a lawsuit over Marvin Booker, who died in Denver County jail. The city lost that trial and had to pay Booker's family $6 million. A few years later, when city attorneys received similar allegations of negligence stemming from Michael Marshall's death, they took a different position and negotiated with Marshall's family.

"That was a case where I think the City of Denver made a very prudent decision to engage in early settlement negotiations," she said. "It is entirely possible a jury would have awarded significantly more than what that settlement ended up being because it was such an outrageous and horrible killing."

Jamie Torres, City Council member and president, told us she and her colleagues are usually ready to approve settlements when they show up on their agenda. Though Council members only find out about these payments one or two weeks before they're asked to vote on them, and though they don't often have the details of each case, a settlement on the agenda means both parties did come to an agreement.

"If both parties have agreed to settle, I don't have a reason to oppose that," she told us. "The frustration I often feel is: And then what? What did we learn from it? What did we change?"

Denver's budget has contingency money tucked away to pay for settlements, Torres said, though that money could be used for other things, like infrastructure projects that go over budget and need extra funding to finish up.

Snezhanna Singleton, financial director for Denver's City Attorney, told us her office fields more than 600 claims and 100 lawsuits each year.

"Each lawsuit and claim is evaluated on its own merits to determine how to proceed," she wrote us. "Cases are settled for a variety of reasons, and the settlement of a lawsuit or claim does not necessarily mean that the City is liable for the claims alleged or admitting fault."

Police reform advocates say this is proof there's still work to do.

While some have linked the rise in payouts directly to Chief Paul Pazen, who recently announced his retirement, Newman said she feels the trend is more about ongoing and systemic problems with policing in general. 2020's protests may have been a once-in-a-generation occurrence, she said, but the police's handling of them were symptoms of larger problems.

"The protests, people characterize as an unprecedented event. But what isn't unprecedented is our police departments' inappropriate responses," she told us. "The response was predictable, given failures in training and supervision."

Not all of 2022's settlements were tied to the uprising in 2020. One had to do with an incident in 2019, when officers pummeled Justin Lecheminant in his backyard after he drove away from a traffic stop; he was awarded $450,000. Keilon Hill was awarded $100,000 after an officer called him a "turd" while responding to a fender bender; Hill alleged he was racially profiled. Brian Loma and Mikel Whitney were each awarded $64,001 after they were arrested for using bad words in 2018.

Robert Davis, head of the Taskforce to Reimagine Denver Policing, said the payouts are unconscionable.

"It is patently unfair that police departments are asking for more and more money, when they are the ones that are costing the taxpayers the most amount in payouts and lawsuits," he told us.

Denver Police regularly asks for more funding during the city's budgeting process.

Both Davis and Newman said they hope a new mayoral administration will improve the city's police department and lessen the need for settlements. Denver will hold municipal elections in spring 2023.

While Davis said his task force will not endorse any candidates, they plan to publish a report card on candidates' past actions and positions on police reform to help inform voters' choices.

"What I hope, more than anything, is that we will have a mayor and administration that actually engages with community in a meaningful way," he said. "I understand that we won't agree on all policies, but it's so important that people come to the table in good faith."

Davis' group was working with DPD on a reform effort back in 2020. The department ended their relationship with them under Director of Safety Murphy Robinson, but has since reengaged with Robinson's successor, Armando Saldate.

Torres said anyone running for mayor will have a "glaring omission" in their platform if they don't talk in specifics about policing and public safety. She added Denver did do some work to curb police brutality in response to 2020's protests, like banning choke holds and requiring body cameras, but said rubber-stamping payouts to people harmed by the city's officers still bothers her.

"Sometimes it's not very satisfying," she said. "It's tough to see that, but I know that incrementally there are things that improved."

Update: The City Attorney's office answered a few more of our questions after this published, and we added some of that context.