Back in 2013, the City of Englewood sold a decrepit 1915 train depot for the discounted rate of $30,000 to Tom and Patti Parson. As part of the deal, the couple promised to preserve and refurbish the depot and turn it into a letterpress printing museum and community hub now dubbed the Letterpress Depot, run by the nonprofit Englewood Depot.

The couple secured a conservation easement, ensuring the building would always be protected as a historic site. They set to work rehabbing the building and also forming and running their nonprofit off-site.

Happy preservation story, right?

Not even a decade later, Englewood's city attorneys are claiming fraud and want the Parsons to finish the work or hand the building back.

Over the summer, city attorneys sent a letter threatening to sue the Parsons. The city requested a timeline on the completion of the project and assurances that it would be wrapped soon. Alternately, the city offered to buy the building for the price of the renovations the Parsons had completed and lease some of the building back to the museum.

The city had discovered 21 improvements the Parsons said would be completed that had yet to be finished.

If they didn't come to an agreement, the letter stated, the couple and nonprofit would face a lawsuit that the city attorneys would fight without legal expenses -- a luxury the Parsons clearly didn't have.

The complaint, the city attorneys threatened, would be for "violation of the Colorado Constitution's anti-donation clause; unjust enrichment; fraudulent inducement; fraudulent misrepresentation; and breach of contract."

The Parsons responded with a 36-page letter detailing both the work they have put into the building, their plans to continue it, and the programming they have undertaken in trying times, including during the pandemic.

Tom Parson believed it was a thorough and thoughtful response. City brass disagreed.

"Defendants did not provide a detailed timeline for the renovation or any assurance of completion," Englewood spokesperson Chris Harguth said. "Instead, the defendants' responses consisted of detailed and superfluous descriptions of what it hoped to complete at an uncertain future date, without a guarantee that the City of Englewood and its citizens would ever realize the benefit of the bargain that formed the basis of the city's decision to transfer title to the defendants."

The city attorneys responded in late September by filing a lawsuit against the Parsons and their nonprofit, Englewood Depot.

The complaint stated they committed fraud by telling city officials they had the money to fund the first stages of rehabilitation of the building and have delivered little in the way of promised construction.

The suit also claimed they have failed to deliver a variety of promised programming, including mentorships with artists and workshops for high schoolers. But the Parsons maintain their organization has done much of that, albeit, off-site, as the building's restoration is far from finished.

What the group hasn't been able to do, while waiting for renovations to be complete, will be done in time, Parson said.

"On its face, the contract did not have a timeline for completion, and that is why we did not file suit for breach of contract on that basis," Harguth wrote. "Instead, we are claiming they were unjustly enriched by obtaining title at a reduced price without taking action as promised in their proposal; that they fraudulently induced the city into transferring title because the proposal stated they had enough money on hand to complete the main floor of the renovation to make it operational when they did not; and that they breached the contract in that they did not notify the city of two title transfers to allow us to exercise our first right of refusal."

In the initial proposal, the Parsons said they anticipated the work being completed within "a year or more."

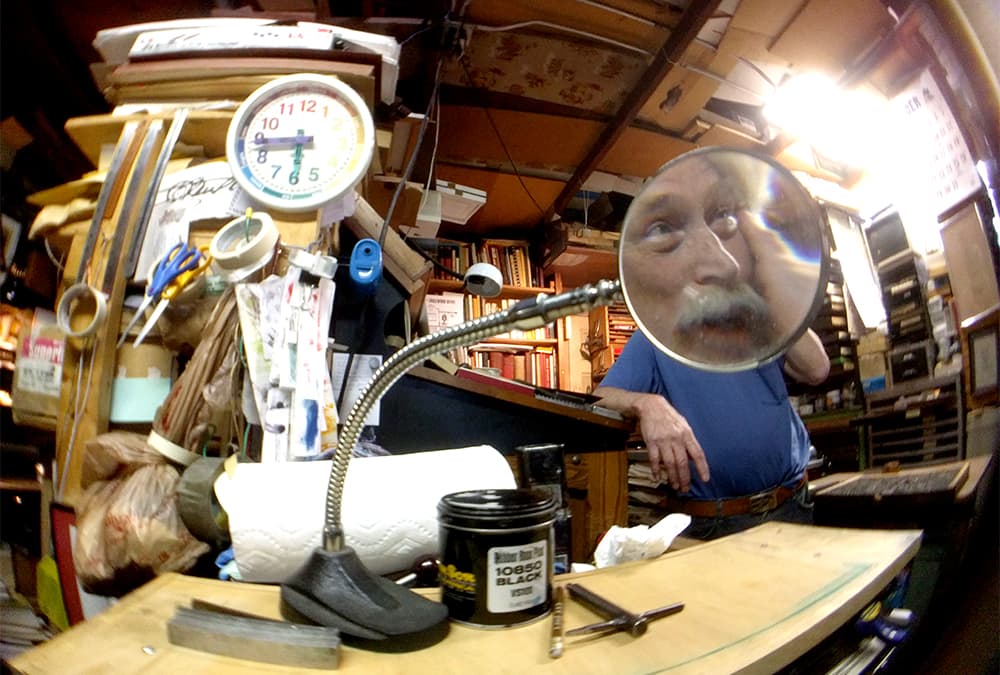

Now $175,000 poorer and mired in years of renovations, Parson said he's poured his life and savings into rehabbing the building, which he described as "a work in progress." He's hardly "enriched." And as for the transfer of titles, they were legal formalities -- not substantive changes in ownership.

"I'm pretty wary of the city at this point," Parson said. "They're out after me. And I didn't do anything, because as far as I can see, I've done nothing but do what we said we would do and give my time and my money and my equipment and my knowledge of printing to make this thing happen."

The Englewood Depot plans to combat the lawsuit and is currently looking for a lawyer.

The nonprofit plans to fight the lawsuit, all while overseeing the installation of a new electrical system and other construction and continuing to offer community programming, Parson said.

Englewood Depot has kept records of its repairs, which are many. The lawsuit, itself, spells out some of the permits the group has filed with the city, indicating the work in progress has, indeed, been in progress. But only three of five permits pulled for construction work have led to completed projects over the years. One expired, and another is pending, according to the complaint.

Parson admitted he's made changes to the order of repairs he committed to in 2013 and some have not yet happened. The scope of work needed to refurbish the depot has been far more than anybody predicted. There was structural damage to the building that had to be addressed before the planned repairs began.

The rehabilitation and creation of the museum is a "lifetime project," he said.

"The property we acquired in 2013 was functionally a deteriorated storage building," Englewood Depot wrote to the city over the summer. "There are many steps in the process to make it fully functional for public use. Yet our rehabilitation work, our historic collections and resources, our active programs and community involvement, all in fact are the living museum which we envisioned and proposed."

The pandemic and supply chain shortage have pushed back construction longer than anyone wanted. COVID-19 restrictions disrupted the nonprofit's ability to host in-person events off-site, but like many groups, the group continued to offer programming online.

The city claimed some of the programming the Parsons have created in the building has been in violation of city law.

"The Parsons have failed to achieve a certificate of occupancy from the city which certifies a building's compliance with applicable building codes and laws," Englewood noted in a statement. "The city has documented multiple violations of city code, including hosting public events in a facility that does not meet basic life-safety requirements of building and fire codes."

The city claimed it tried to work directly with the Parsons and the nonprofit and that its efforts have been unsuccessful.

"Filing suit was certainly a last resort, but the city and its citizens deserve the community space they were promised," said Englewood Mayor Othoniel Sierra, in a statement. "We've worked diligently to negotiate a proposal that would be equitable to both parties. But unfortunately, those efforts failed so we were required to seek court intervention."

Harguth said the city would prefer the Parsons to complete the work rather than have the city repossess the building.

"The City of Englewood simply desires for the defendants to do what they said they would do," he wrote.

There is no attempt at a property grab for profit on the part of the city, he added.

"The City has no future plans for the land and building, and has not received any proposals or offers to purchase or renovate the building from a third party," Harguth wrote.

Parson said he's ready to go to court if he has to do so.

"At this point, we just want to make it real clear that we're not going to be intimidated by this," he said. "We're doing something that's valuable and useful, and we're doing it at our own pace, and we own the property. And we bought it legitimately. We didn't defraud anybody about it, and we're doing what we said we would do.

"If that takes convincing a judge, we'll go convince a judge," he said.