Westsiders drank and drank and drank for nearly 100 years at the White Horse Bar, where fights were rare and the company was mostly good.

Getting sloppy never cost too much at the Westwood dive, at Alameda Ave. and Sheridan Blvd.

Neighbors would stumble over to meet friends and family. Musicians would belt out songs. Visitors to Denver, in town for the annual Denver March Powwow, would spread the word that the White Horse was a home away from home for Native people.

The bar has even been memorialized by author Erika T. Wurth, who named her recently published novel after it.

The doors are locked these days, though.

Cats wander the parking lot. Richard Senst, who owned the bar for over four decades ever since his previous bar was flooded out of Rapid City, South Dakota, continues to feed the strays from bags of food donated by former patrons.

Senst is not ready to sell the bar, but his doctor tells him it's time. So he listed the property for $1.5 million dollars, and he's not willing to take a penny less.

Senst, whose grandfather owned a pool hall and father owned a bar, said most of the White Horse old timers are now dead. Even some of their kids are gone.

Though the bar is no longer open, he wishes it was -- as do the neighbors and people coming to town for powwows.

Many, including Senst, hope the White Horse rides again. But the bar is trapped between life and death, old and new Denver, a rich history and an uncertain future.

Turn the key and the White Horse Bar could easily be resurrected as one of the city's oldest and last dives.

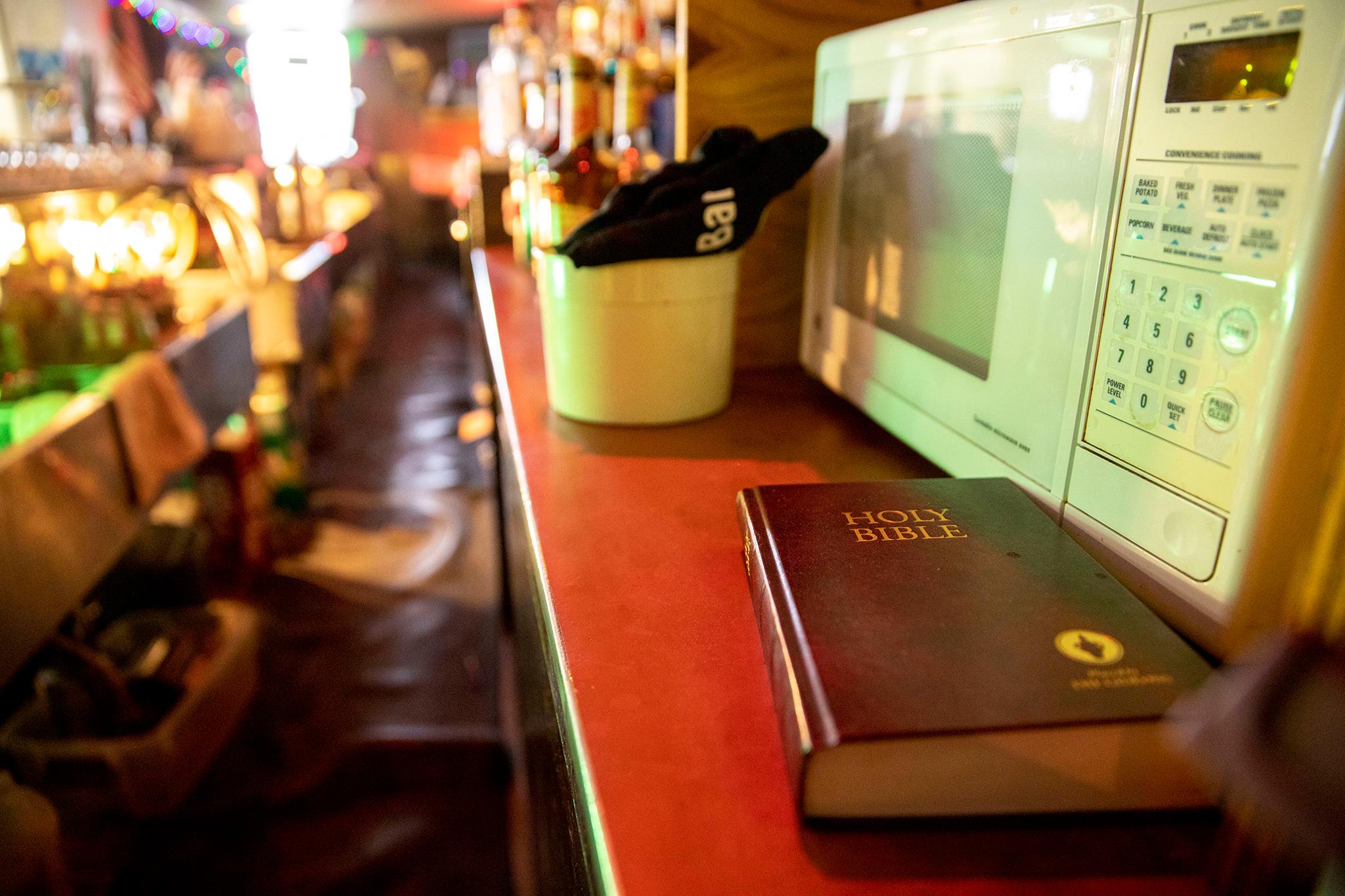

Liquor bottles line the scarred counter. The doors are still tattooed with COVID-19 warnings: "Masks required." Deals scrawled on signs are affixed to wood paneling: two shots of Canadian Club for $6, any five shots for $20, or buy two, get the third one free from 4 to 7 p.m.

Senst served in Vietnam. He's fond of grumbling with gravel in his voice, "Nobody asked to be here." Asked about memorable stories about customers, he shrugged off the task, citing his bad back. "It would take a small book for that."

From the jukebox, Toby Keith sings "I Love My Bar" and Sheryl Crow and Kid Rock croon about putting each other's pictures away. Christmas lights dangle above wobbly barstools. Pool tables wait for somebody to rack eight balls. Buried under a few chairs, a makeshift stage is ready for performers. Even better, the White Horse cabaret license is still up to date.

The signs around the dive say plenty: No gambling. Beware of pickpockets and drunks. Drinking is encouraged. Please pay when served. B-21-Behave-Or-B-Gone. This establishment is under 24-hour video surveillance. We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.

But the bar, Senst said, served everyone, and he has the photos to prove it.

There's a black-and-white shot of the old landlords and staff from the '70s, a colorful one of patrons grinning, another of scooter riders outside, and a headshot of John Elway, who often dropped into the White Horse during his Super Bowl years.

Sculptures and paintings of white horses are scattered throughout, along with American flags.

A bible rests behind the bar, a testament to Senst's personal belief that sin -- which fueled barroom fights over the years -- occurred because "people just haven't been born again."

"They haven't accepted their father in heaven and changed their ways," he said. "God loves them. He wants them to change, too. He wants everybody to change."

Will the White Horse carry on as a bar? Senst hopes so. But he's not in a position to rule out offers.

Realtor Sofia Williamson, who's representing the property, has had a few people show interest. Like Senst, she hopes the new owners preserve this little slice of westside history. But so far, it's not preservationists eager to save the White Horse eying the property.

"Somebody called the other day, and they want to put a drive thru," she said. "There's enough drive thrus. For me, it's sad, because I grew up here."

Senst has watched local restaurants and bars be bulldozed to make way for fast-food chains, like the nearby Burger King.

"They've kind of pushed the little mom-and-pop restaurants out of business," Senst said. "Not completely, but they didn't help. Corporate America is what I call it, and I don't like that."

The area has too many apartments to justify razing the White Horse and building more, Williamson said, though that is one likely outcome in a city with too few houses for the number of people who now live here.

What Westwood needs more than apartments, Williamson said, is somebody who wants to preserve what makes the neighborhood special.

Perhaps Elway could save the place, she mused, but also acknowledged it's possible the White Horse will be demolished and replaced with something new.

"When I came here, wherever you went in the city, everything had a small-town feeling," Senst said. "But that's not true anymore. That's the only way I know how to say it. And I liked it better that way. You got the -- I got to watch what I say. You got the big money running things. I mean, big money. Hell, I don't blame them. This is America."